When stonecutters carved Thomas Brierley's gravestone in 1785, they didn't use ordinary letters. Instead, mysterious geometric symbols—angles, corners, and dots in cryptic patterns—adorned the memorial. These strange markings appeared meaningless to casual observers. Fellow Freemasons, however, could read the sacred phrase: "Thomas Brierley made his ingress July 16th 1785." This was the pigpen cipher, a geometric substitution system with a remarkable 500-year history spanning mystical traditions, secret societies, military campaigns, and modern education.

The pigpen cipher—also known as the masonic cipher, Freemason's cipher, tic-tac-toe cipher, Rosicrucian cipher, and Napoleon cipher—is a geometric substitution cipherthat replaces each letter of the alphabet with a unique symbol derived from grid fragments. Unlike traditional letter-based ciphers, pigpen uses visual patterns: tic-tac-toe grids and X-shaped diagrams create 26 distinct symbols through their compartments and dots. This cipher became so closely associated with 18th and 19th century Freemasonry that "Masonic cipher" remains its most common alternative name today.

The pigpen cipher history traces ancient roots in Jewish Kabbalistic mysticism through Freemason adoption to American Revolution and Civil War applications. This simple geometric code captured imaginations across centuries. While modern standards consider it cryptographically weak, the cipher endures as an educational tool, puzzle element, and cultural artifact that reflects humanity's enduring fascination with secret writing.

This comprehensive guide explores the complete pigpen cipher history: its mystical origins in 1531 and earlier, secret society adoption by Rosicrucians and Freemasons, military and political applications, notable historical cases from pirate treasures to wartime communications, cipher variants and evolution, cryptographic analysis, and its remarkable modern revival in education and popular culture.

What Is the Pigpen Cipher?

The pigpen cipher is a geometric substitution cipher that replaces letters with symbols formed from grid fragments. First documented by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in 1531, this cipher uses tic-tac-toe grids and X-shaped patterns to create 26 unique geometric symbols—one for each letter of the alphabet. Each symbol represents the shape of its compartment within the grid system, with dots distinguishing similar shapes. Despite its visual complexity, the pigpen cipher functions as a simple monoalphabetic substitution, offering visual obscurity rather than cryptographic strength.

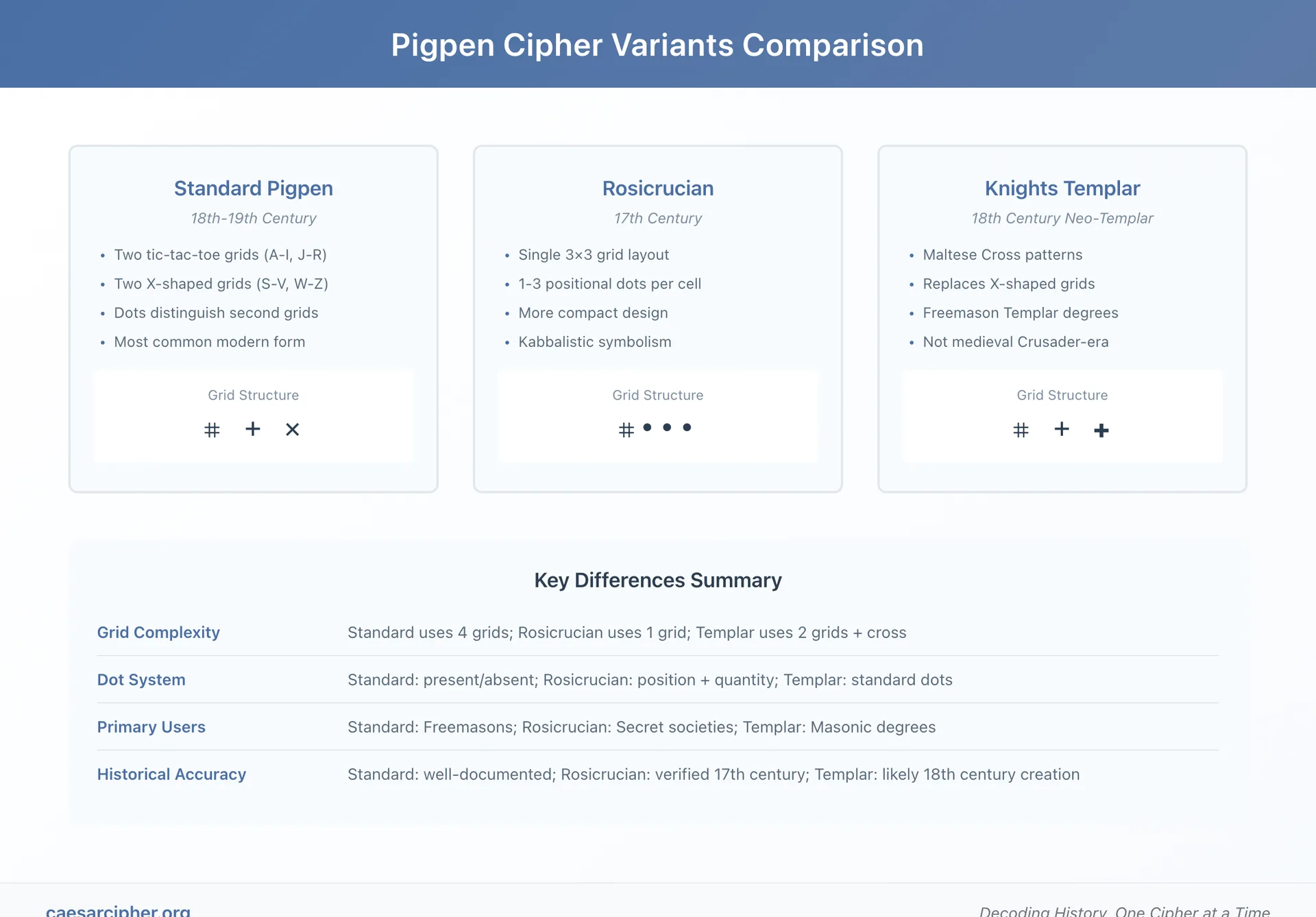

Each alternative name tells part of the cipher's story. The masonic cipher or Freemason's cipher labels reflect its dominance in 18th and 19th century fraternal lodge communications. Tic-tac-toe cipher points to the characteristic grid structure. Rosicrucian cipher acknowledges 17th century secret society variants. The Napoleon cipher name hints at possible French Revolutionary era usage, though evidence remains sparse.

How the Pigpen Cipher Works

The standard pigpen cipher employs a four-grid system creating distinct visual symbols:

First Grid System: Two Tic-Tac-Toe Grids

- Grid 1: Letters A through I arranged in a 3×3 pattern (no dots)

- Grid 2: Letters J through R in a 3×3 pattern (with dots)

Second Grid System: Two X-Shaped Grids

- X-Grid 1: Letters S, T, U, V at the four points (no dots)

- X-Grid 2: Letters W, X, Y, Z at the four points (with dots)

Each letter's symbol consists of the lines forming its grid compartment. For example, the letter "E" occupies the center square of the first tic-tac-toe grid, so its symbol is a square (⃞). The letter "N" occupies the center of the second grid, producing a square with a dot (⃞•). The letter "T" sits at the bottom point of the first X, creating a downward-pointing angle (∨).

The dot system serves a crucial function: distinguishing the second grid from the first in each pair. Without dots, "A" and "J" would share identical symbols since they occupy equivalent positions in their respective grids. The addition of a dot to all second-grid symbols creates unique markers for all 26 letters.

Why "Pigpen" Cipher?

The name "pigpen cipher" derives from the visual resemblance between the tic-tac-toe grid symbols and the fenced enclosures used to contain pigs on farms. The compartmentalized grid structure—with its angular divisions creating small "pens"—evoked rural livestock enclosures to early observers. This agricultural metaphor, though prosaic compared to "Masonic" or "Rosicrucian," captured the cipher's essential character: a system of geometric compartments, each holding its secret.

Unlike letter-based substitution ciphers that simply replace A with Z or shift the alphabet, pigpen transforms text into angular patterns resembling abstract art, architectural diagrams, or mysterious runes. This visual transformation created psychological barriers beyond its mathematical security. Unfamiliar symbols intimidate readers more effectively than scrambled letters—even when both offer the same weak protection.

Pigpen Cipher Origins and Early History

Pre-Agrippa Conceptual Roots: The Kabbalistic Nine Chambers

Long before the pigpen cipher appeared in Western cryptographic texts, Jewish Kabbalistic tradition employed a conceptually similar system called the "Nine Chambers" (Aiq Bekar). This ancient Hebrew mystical practice organized the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet into geometric grids, assigning spiritual and numerical significance to each position. Rather than serving cryptographic purposes, these nine-chamber arrangements functioned as tools for religious meditation, gematria (Hebrew numerology), and sacred symbolism.

The Kabbalistic nine-chamber system divided the Hebrew alphabet into groups arranged in a 3×3 matrix. Some positions contained multiple letters distinguished by dots or positional marks (1-3 dots per compartment). This grid-and-dot methodology bears striking resemblance to later pigpen configurations, suggesting cultural transmission from Jewish mystical traditions through Renaissance occult philosophy to practical cryptography.

The purpose of these early grid systems differed fundamentally from modern encryption. Kabbalistic practitioners sought to unlock divine secrets and explore the mystical properties of letters and numbers, not to conceal messages from adversaries. Yet the mechanical structure—letters organized in geometric grids with distinguishing marks—laid conceptual groundwork for the pigpen cipher's eventual development.

Agrippa's 1531 Documentation: First Written Description

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, the German occult philosopher, provided the first clear documented description of what we recognize as the pigpen cipher system. In his influential 1531 work Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Agrippa described the "Kabbalah of the Nine Chambers"—a grid-and-dot encoding system derived from Hebrew mystical traditions.

Agrippa's description detailed how Hebrew letters could be arranged in a 3×3 grid system, with positions distinguished by dots. Though primarily presenting this system within the context of Renaissance occultism and hermetic philosophy, Agrippa formalized the mechanism that would later become the pigpen cipher: geometric compartments creating unique letter symbols through grid fragments and dot placement.

Who Invented the Pigpen Cipher?

No single inventor created the pigpen cipher. The system evolved through cultural transmission across multiple traditions and centuries. Ancient Kabbalistic practices provided conceptual ancestors. Agrippa's 1531 documentation offered the first Western written formalization. Multiple independent developments likely occurred across different cultures and time periods, with practitioners adapting grid-based letter systems for mystical, religious, or practical purposes.

Agrippa himself did not "invent" the cipher but rather documented existing traditions, bridging Jewish mysticism and Renaissance occult scholarship. His work served as a crucial transmission point, bringing nine-chamber grid concepts from esoteric religious contexts into the broader intellectual environment of 16th century Europe.

Transition from Mystical to Cryptographic

Throughout the 16th and early 17th centuries, the cipher shifted from religious symbolism toward practical concealment. Renaissance interest in occult knowledge, secret societies, and hermetic traditions created an environment where geometric encoding systems flourished. Mystical meditation tools transformed into systems for protecting sensitive communications.

Scattered evidence suggests individual usage during the 16th century—personal notes, private journals, and correspondence employing geometric symbol substitution—though documentation remains fragmentary. Early adopters recognized that grid-based symbols offered visual obscurity. Recipients unfamiliar with the key saw meaningless geometric patterns rather than recognizable letters.

This transitional period laid foundations for later secret society adoption. The cipher's mystical heritage appealed to organizations interested in ancient wisdom and esoteric knowledge. Its practical simplicity suited fraternal groups needing basic communication security without complex cryptographic expertise.

The Rosicrucian Connection

17th Century Secret Society Adoption

The Rosicrucian Brotherhood, a mystical and philosophical secret society that emerged in 17th century Europe, embraced the pigpen cipher system during the height of its cultural influence. Rosicrucians combined interests in alchemy, Kabbalah, hermetic knowledge, and Christian mysticism, creating an intellectual environment where geometric cipher systems resonated with both practical and symbolic significance.

Rosicrucian fascination with ancient wisdom traditions—including Kabbalistic numerology and sacred geometry—made the nine-chamber grid system particularly attractive. The cipher connected members to perceived ancient mysteries while providing practical means for private internal communications within the brotherhood.

The Rosicrucian Cipher Variant

The Rosicrucian variant employed a distinctive configuration that differed from later standardized pigpen forms:

Key Characteristics:

- Single 3×3 grid rather than the later two-grid system

- 1-3 positional dots within each cell distinguished multiple letters

- More compact than the Freemason two-grid, two-X configuration

- Greater emphasis on mystical symbolism alongside encryption functionality

This single-grid approach created a denser symbol set where dot position and quantity conveyed meaning beyond simple presence or absence. The Rosicrucian cipher thus maintained closer ties to its Kabbalistic origins, where dot placement carried spiritual significance.

Bridge to Freemasonry

The Rosicrucian cipher served as a crucial evolutionary link between Renaissance occult traditions and Enlightenment-era Freemasonry. Both secret societies shared interests in ancient mysteries, symbolic rituals, and fraternal privacy. As Freemasonry rose to prominence in 18th century Europe, it inherited and adapted the cipher tradition pioneered by Rosicrucians.

The 17th century Rosicrucian adoption demonstrated the cipher's adaptability to organizational needs—how geometric symbol systems could serve both ceremonial purposes and practical communications within secret societies. This dual character—simultaneously mystical and functional—would define the pigpen cipher's most famous association: the Freemasons.

Freemason Adoption: The Golden Age

Systematic 18th Century Adoption

The early 18th century launched the pigpen cipher's golden age through systematic adoption by Freemason lodges across Europe and colonial America. Scattered individual usage and secret society experimentation gave way to standardized fraternal practice. Freemasons employed the cipher so extensively throughout the 1700s and 1800s that "Masonic cipher" and "Freemason's cipher" became—and remain—the system's most common alternative names.

Freemason adoption transformed the cipher's identity. The pigpen cipher became synonymous with Freemasonry itself, no longer primarily associated with mystical traditions or niche groups. Masonic usage grew so ubiquitous that encountering geometric grid symbols on 18th or 19th century artifacts immediately suggested Freemason origins.

Uses and Applications

Lodge Records and Documentation

Freemason lodges employed the pigpen cipher extensively for internal record-keeping:

- Meeting minutes recording lodge business, decisions, and discussions

- Ritual documentation preserving the specific words, gestures, and ceremonies of Masonic rites

- Membership information including names, initiation dates, and advancement through degrees

- Organizational correspondence between lodge officers and Grand Lodge authorities

This documentation served fraternal privacy rather than military secrecy. Freemasons sought to maintain internal affairs away from public scrutiny while preserving institutional memory across generations.

Physical Evidence and Artifacts

The most visible evidence of Freemason pigpen usage appears on physical objects that have survived to the present day:

Gravestone Inscriptions The most striking examples appear in 18th and 19th century cemeteries:

- Trinity Church Cemetery, New York City (established 1697) contains multiple Freemason graves with pigpen inscriptions

- Thomas Brierley grave marker (July 16, 1785) features the complete inscription "Thomas Brierley made his ingress" in geometric cipher symbols

- Common phrases like "Memento Mori" (Remember Death) frequently appeared encoded on Masonic tombstones

- Colonial American cemeteries from Massachusetts to Georgia preserve pigpen-inscribed memorials

- European Masonic burial grounds similarly display encoded epitaphs and memorial dedications

Certificates, Medals, and Tokens

- Membership certificates awarded upon initiation or degree advancement

- Commemorative medals celebrating lodge anniversaries or significant events

- Tokens used for lodge admission or identification

- Official charters establishing new lodges

These artifacts transformed the pigpen cipher from ephemeral communications into permanent physical records, ensuring its preservation and study by later generations.

Why Freemasons Chose Pigpen

Symbolic Resonance

Freemasonry's central symbolism revolves around geometry, architecture, and building—represented by the square, compass, and other tools of stone masonry. The pigpen cipher's geometric grid structure resonated perfectly with Masonic philosophical emphasis on sacred geometry, mathematical harmony, and architectural precision. Using a cipher based on geometric patterns reinforced the brotherhood's foundational metaphors.

Practical Simplicity

Unlike complex polyalphabetic ciphers or codebooks requiring extensive key management, the pigpen cipher offered straightforward implementation:

- Members could learn the system in a single session

- No complex keys to memorize or secure

- Simple pen-and-paper implementation without mechanical aids

- Visual distinctiveness made encrypted text immediately recognizable to initiated members

Fraternal Privacy vs. Military Secrecy

Crucially, Freemasons sought fraternal privacy rather than military-grade security. The goal was not to resist determined cryptanalysis by professional codebreakers but rather to:

- Maintain separation between Masonic affairs and public knowledge

- Create a shared secret reinforcing brotherhood bonds

- Preserve ritual sanctity by limiting access to the uninitiated

- Signal membership through recognizable symbols

The cipher's cryptographic weakness mattered less than its social function: creating boundaries, signaling membership, and providing psychological satisfaction of "secret knowledge."

Tradition and Continuity

By adopting a cipher with roots in ancient Kabbalistic traditions (or perceived ancient roots), Freemasons connected themselves to a prestigious lineage of hidden wisdom. The nine-chamber heritage suggested timeless mysteries and esoteric knowledge—exactly the cultural capital Freemasonry cultivated.

Cultural Impact and Popular Perception

Freemason adoption embedded the pigpen cipher deeply in Western cultural consciousness. Even today, geometric grid symbols trigger associations with secret societies, hidden meanings, and mysterious brotherhoods. This cultural resonance far outlasted the cipher's practical utility. Symbols can maintain power long after their original purposes fade.

Widespread Masonic usage ensured the cipher's preservation. Many obscure historical cryptographic systems survive only in fragmentary mentions. The pigpen cipher's extensive physical evidence—thousands of gravestones, certificates, and artifacts—provides rich documentation for historians and cryptographers.

Decline of Masonic Usage

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Freemason usage of the pigpen cipher declined significantly:

- Increased public knowledge eliminated the cipher's obscurity value

- Organizational changes within Freemasonry reduced emphasis on secretive practices

- Cryptographic obsolescence became undeniable as frequency analysis techniques spread

- Cultural shifts made elaborate secrecy seem less culturally necessary

The cipher transitioned from active communication tool to historical artifact and ceremonial relic within Masonry itself. Modern Freemasons recognize and appreciate the pigpen cipher's heritage while rarely employing it for actual communication security.

Military and Political Applications

American Revolution Usage (1775-1783)

The pigpen cipher saw documented military application during the American Revolutionary War, employed by both British forces and the Continental Army for covert communications. In an era when intercepted messages could reveal troop movements, supply routes, or strategic plans, even simple ciphers provided valuable protection against casual examination by enemy patrols or sympathizers.

George Washington's Army

The Continental Army under George Washington documented pigpen cipher variants with adaptations designed to enhance security:

- Randomized letter placement: Some variants abandoned standard alphabetical grid arrangement (A-I, J-R, S-V, W-Z) for keyword-based orders

- Keyword-based grids: Starting with a keyword like "LIBERTY" and filling remaining letters

- Custom configurations: Unique grid arrangements known only to specific commanders or units

These variations increased obscurity by eliminating the predictable standard arrangement. Enemy cryptanalysts who recognized the geometric symbols as pigpen still needed the specific letter-to-grid mapping—adding protection beyond the basic system.

The cipher's practical advantages in Revolutionary War contexts included:

- No complex key management: Unlike codebooks requiring secure distribution and protection, the cipher key could be memorized

- Quick implementation: Field commanders could encode urgent messages rapidly

- Minimal training required: New cipher clerks could learn the system in minutes

- Visual unfamiliarity: British soldiers unfamiliar with Masonic traditions might not immediately recognize the cipher

American Civil War Applications (1861-1865)

Union Prisoners in Confederate Camps

The American Civil War witnessed notable pigpen cipher usage by Union soldiers held in Confederate prison camps. These desperate circumstances transformed the cipher from a fraternal curiosity into a survival tool:

Communication Purposes:

- Covert messaging between prisoners coordinating activities or sharing information

- Letters to outside contacts smuggled from camps with encoded sections

- Escape planning discussed without alerting guards to specific plans

- Documentation of conditions recording abuses or intelligence for later testimony

Effectiveness in Prison Context:

The cipher succeeded not through cryptographic strength but through guards' unfamiliarity. Confederate prison guards who intercepted messages saw meaningless geometric symbols rather than recognizable text. Without knowledge of cipher systems or access to cryptanalytic resources, guards often dismissed the symbols as decorative doodling, mathematical diagrams, or meaningless scribbling.

Surviving correspondence examples from Civil War prisoners preserve these encoded communications, now housed in archives and museums. Historians have deciphered many messages, revealing the ingenuity and resilience of imprisoned soldiers who maintained clandestine communication networks under harsh conditions.

Security Through Obscurity

Effectiveness Assessment

Military and political pigpen usage relied entirely on security through obscurity—the principle that unfamiliarity with a system provides protection:

When It Worked:

- Adversaries unfamiliar with geometric substitution ciphers

- Low-stakes situations where casual interception posed the primary threat

- Contexts where speed mattered more than cryptographic strength

- Environments lacking professional cryptanalytic capabilities

When It Failed:

- Against opponents with cipher knowledge (including Freemasons on opposing sides)

- Against systematic frequency analysis by trained cryptanalysts

- In high-security situations where captured messages received serious scrutiny

- After widespread publication made recognition trivial

The pigpen cipher offered no mathematical security properties beyond basic letter substitution. Its sole advantage—visual unfamiliarity—evaporated upon recognition. Modern cryptographic standards would classify it as "toy cipher" quality, suitable only for educational purposes.

Other Political and Diplomatic Uses

Beyond major military conflicts, the pigpen cipher appeared sporadically in:

- Diplomatic correspondence (limited 18th-19th century usage)

- Political organization communications (secret societies, underground movements)

- Resistance group messaging (various historical contexts)

- Spy craft (primarily amateur or low-level intelligence work)

These applications shared common characteristics: environments where sophisticated cryptanalysis was unlikely, situations requiring simple field-implementable systems, and contexts where Masonic cultural associations provided cover for cipher usage.

Notable Historical Cases

Olivier Levasseur's Treasure Cryptogram (1730)

The Pirate's Last Mystery

On July 7, 1730, French pirate Olivier Levasseur—nicknamed "La Buse" (The Buzzard)—stood before executioners in what is now Réunion Island. As the noose tightened around his neck, Levasseur threw an encoded necklace toward the assembled crowd, reportedly shouting: "Find my treasure, whoever understands this!"

The 17-Line Cryptogram

The cryptogram Levasseur threw allegedly reveals the location of a vast treasure accumulated during years of piracy in the Indian Ocean—potentially including plunder from Portuguese vessels, captured merchant ships, and colonial settlements. The 17-line document combines pigpen cipher symbols with additional cryptographic elements, creating a multilayered puzzle that has resisted definitive solution for nearly three centuries.

Legend vs. Reality

The Levasseur treasure remains one of cryptography's enduring mysteries:

- No verified decryption has produced a treasure discovery accepted by historians

- Multiple claimed solutions have emerged over decades, none conclusively validated

- The treasure's existence itself remains unverified—legendary rather than documented

- Cultural persistence keeps the mystery alive through books, documentaries, and treasure hunters

The Levasseur cryptogram demonstrates the pigpen cipher's capacity to capture public imagination. Whether or not treasure ever existed, the image of a condemned pirate throwing his final secret to the crowd—encoded in mysterious geometric symbols—embodies romantic notions of hidden wealth and cryptographic adventure.

Major George Logue's Diary (1852)

A Dark Chapter Encoded

In stark contrast to romantic pirate legends, Major Logue's diary from 1852 Western Australia reveals the pigpen cipher's use in concealing atrocities. The Irish-Australian pastoralist employed geometric symbols to document his participation in the massacre of Aboriginal Yamatji people in the Ellendale, Walkaway, and Greenough River areas.

Content and Discovery

Logue's diary entries, written in pigpen cipher, detailed violent attacks that killed at least 19 Aboriginal people. The encryption served to hide evidence of crimes from potential discovery by authorities or disapproving contemporaries. When historians later deciphered the diary, its revelations provided crucial documentation of colonial violence and Aboriginal resistance.

Historical Accountability

This case demonstrates how ciphers serve not only noble purposes but also concealment of wrongdoing. Logue's choice to encrypt massacre documentation—rather than simply not recording it—suggests:

- Desire to preserve personal record without external accountability

- Assumption that geometric symbols provided adequate protection

- Psychological need to document actions even while hiding them

The decoded diary now serves as historical evidence in understanding colonial-era violence against Indigenous Australians, transforming the cipher from concealment tool into accountability mechanism.

Civil War Prisoner Correspondence

Letters from Confederate Camps

American Civil War archives preserve multiple examples of Union soldier letters containing pigpen-encoded sections. These letters, sent from Confederate prison camps to family, friends, or Union contacts, exemplify the cipher's role in desperate circumstances:

Typical Content:

- Prison camp conditions and treatment

- Health status of specific prisoners

- Messages requesting aid or intervention

- Coordination information for escape attempts

- Intelligence about Confederate activities visible from camps

Methods and Risks:

Prisoners employed various techniques:

- Partial encoding: Mixing plaintext and ciphertext to reduce suspicion

- Hidden messages: Encoding sensitive information while discussing innocuous topics in plaintext

- Distributed information: Splitting encoded content across multiple letters to reduce individual message significance

Discovery of cipher usage risked punishment, yet soldiers continued the practice—testament to communication's fundamental importance even under harsh conditions.

Additional Historical Instances

Beyond these prominent cases, pigpen cipher usage appears throughout 18th and 19th century contexts:

- Personal diary entries protecting private thoughts and observations

- Time capsule messages intended for future discovery

- Memorial dedications on buildings and monuments

- Secret society correspondence beyond Freemasonry (various fraternal organizations)

Each instance reflects the cipher's dual nature: simultaneously practical (providing basic concealment) and symbolic (signaling membership in communities of secret knowledge).

Pigpen Cipher Variants and Evolution

Standard Configuration

The most common modern form of the pigpen cipher employs a four-grid system:

Grid Arrangement:

- First tic-tac-toe grid: A through I (no dots)

- Second tic-tac-toe grid: J through R (with dots)

- First X-shaped grid: S through V (no dots)

- Second X-shaped grid: W through Z (with dots)

This Grid-Grid-X-X arrangement became the de facto standard through Freemason usage and subsequent cryptography textbook presentations. Its balance of simplicity and completeness (covering all 26 letters) made it the natural reference form.

Rosicrucian Variant

The 17th century alternative employed a fundamentally different structure:

Key Differences:

- Single 3×3 grid rather than two tic-tac-toe grids

- 1-3 positional dots per cell (position and quantity both meaningful)

- More compact visual appearance

- Greater symbolic emphasis connecting to Kabbalistic traditions

The Rosicrucian variant demonstrates early experimentation before standardization. Its single-grid approach required more complex dot systems to distinguish 26 letters within nine compartments, creating denser symbolism but potentially greater confusion.

Newark Cipher

The Newark variant substituted visual markers:

Distinctive Features:

- Short lines at various angles instead of dots

- Greater visual variety and complexity

- Distinguishes grid positions without requiring dot presence/absence

- Regional or organizational preference possibly driving adoption

This variant illustrates how basic concepts (grid compartments creating symbols) could accommodate different marking systems while preserving fundamental mechanisms.

Knights Templar Variant

Historical Debate:

The so-called Knights Templar cipher employs Maltese Cross patterns instead of X-shaped grids:

- 18th century Neo-Templar origin most likely (Freemason Templar degrees)

- Not medieval Crusader-era despite frequent claims

- Freemason attribution to Knights Templar tradition part of Masonic mythology

- No verified medieval usage by actual historical Templars

This variant demonstrates how cipher names and attributed origins don't always reflect historical accuracy. Freemasons in the 18th century created Templar-themed degrees and rituals, producing cipher variants that evoked crusader imagery while actually being contemporary creations.

Custom Alphabet Arrangements

Keyword-Based Variants:

Beyond symbol shape variations, many pigpen users customized letter placement:

Methods:

- Keyword initialization: Start with "MASON" (or other keyword) then fill remaining letters alphabetically

- Complete randomization: Arbitrary letter-to-grid mappings known only to correspondents

- Organizational standards: Specific lodges or military units using unique arrangements

Security Enhancement:

These customizations significantly improved security:

- Standard pigpen assumes A-I, J-R, S-V, W-Z grid placement

- Keyword variants eliminate this predictability

- Even recognizing pigpen symbols, cryptanalysts face additional uncertainty

- George Washington's documented randomized variants exemplify this approach

The existence of custom arrangements reveals understanding that the standard configuration's predictability weakened security—showing 18th century users recognized cryptographic principles despite lacking formal terminology.

Why Variants Emerged

Motivations for Diversification:

Multiple factors drove variant development:

- Organizational identity: Different groups distinguished themselves through unique configurations

- Regional adaptations: Geographic separation led to independent evolutionary paths

- Security enhancement: Customization reduced vulnerability to pattern recognition

- Ceremonial purposes: Symbolic variations emphasized mystical or fraternal meanings

- Historical evolution: Natural change across time periods and cultural contexts

The pigpen cipher's fundamental simplicity enabled experimentation. Unlike complex systems where variations might cause catastrophic failures, pigpen's basic grid-and-symbol approach accommodated diverse implementations while maintaining core functionality.

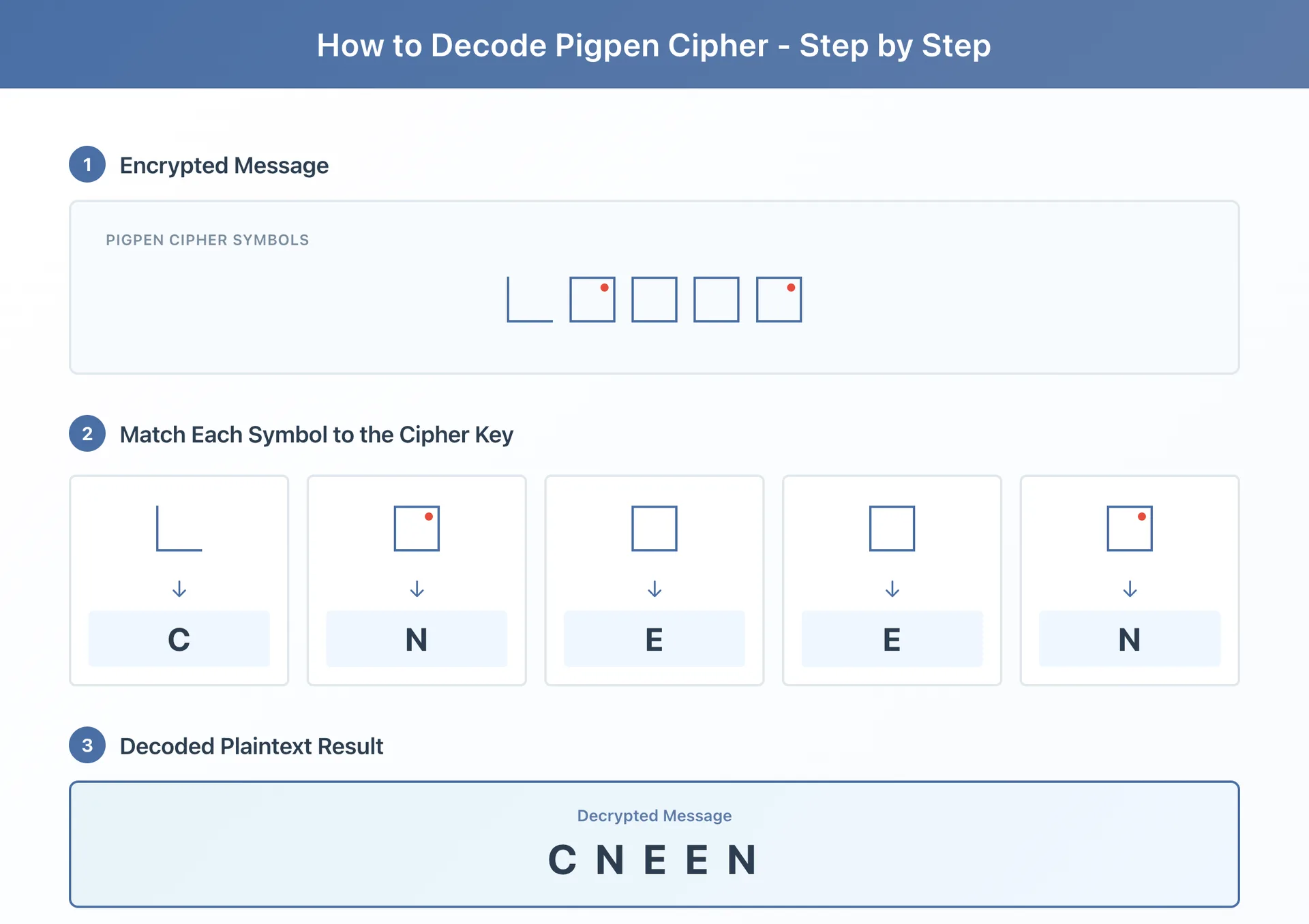

How to Decode the Pigpen Cipher

Step-by-Step Decoding Guide

To decode a pigpen cipher message:

-

Obtain or create the cipher key: Draw two tic-tac-toe grids (3×3 each) and two X shapes. Label the first grid A-I, second grid J-R (add dots), first X with S-V, second X with W-Z (add dots).

-

Examine the first symbol: Identify its basic shape (square corner, T-junction, center square, X-arm angle, etc.) and note whether it contains a dot.

-

Locate the matching grid compartment: Find which grid position produces that exact symbol shape. For example, a right-angle corner opening upward-left indicates position A (top-left of first grid). The same shape with a dot indicates position J (top-left of second grid).

-

Account for the dot system: Dots always indicate the second grid or X in each pair. No dot = first grid/X; dot present = second grid/X.

-

Decode letter by letter: Work systematically through the ciphertext, converting each geometric symbol back to its corresponding letter.

-

Consider variant possibilities: If the standard key doesn't produce readable text, the message may use a variant configuration (Rosicrucian, keyword-based, randomized, etc.).

Practical Example:

The word "HELLO" encodes as:

- H = center square with dot (from second grid, position H)

- E = center square no dot (from first grid, position E)

- L = right middle compartment no dot (position L... wait, L is in the second grid)

This example immediately reveals the cipher's pedagogical value: learners must engage with grid positions, symbol formation, and dot meaning—providing hands-on introduction to substitution cipher mechanics.

Breaking Pigpen Cipher with Frequency Analysis

Cryptanalysis Methodology

Despite geometric symbols, the pigpen cipher remains a simple monoalphabetic substitution—cryptographically equivalent to replacing each letter with an arbitrary different letter. This exposes it to classical frequency analysis:

Attack Steps:

- Count symbol frequencies in the ciphertext

- Compare to standard letter frequencies in the message language (English: E, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R most common)

- Make tentative assignments: Most common symbol = E, second most = T, etc.

- Test and refine: Look for common patterns (THE, AND, -ING endings) to validate assignments

- Iterate until solved: Adjust assignments based on emerging word patterns

Why Symbols Don't Add Security:

The geometric shapes provide zero mathematical security advantage:

- Symbol substitution = letter substitution from a cryptographic perspective

- Visual unfamiliarity ≠ cryptographic strength

- Pattern frequencies remain identical to plaintext frequencies

- Standard monoalphabetic weakness applies fully

Modern perspective: The pigpen cipher is essentially a Caesar cipher with a different alphabet—visually interesting but cryptographically trivial.

Security Assessment:

By any modern standard, the pigpen cipher is not secure:

- Easy to break with basic cryptanalysis knowledge

- Trivial for computers: Automated solvers crack pigpen instantly

- Widespread recognition: Often recognized rather than cryptanalyzed

- No computational barrier: Breaking requires pattern matching, not computational power

Educational Value Only

The pigpen cipher serves exclusively educational purposes today:

- Teaching substitution cipher concepts

- Introducing frequency analysis vulnerability

- Demonstrating security-through-obscurity failures

- Providing historical cipher examples

Never use the pigpen cipher for actual security needs. Any sensitive information requires modern cryptographic systems designed and validated by professional cryptographers.

Modern Breaking Tools

Contemporary technology renders the pigpen cipher completely transparent:

- Online decoder tools instantly recognize and decrypt standard pigpen

- Automated cryptanalysis software solves variants through pattern matching

- Frequency analysis programs crack even randomized versions with sufficient ciphertext

- No special expertise required: Casual users can break pigpen messages in seconds

Pigpen Cipher in Modern Times

Educational Applications

Teaching Basic Cryptography

The pigpen cipher thrives in 21st century educational contexts:

Classroom Uses:

- Introduction to substitution ciphers: Visual symbols make abstract concepts tangible

- Frequency analysis demonstrations: Students learn cryptanalysis by breaking each other's messages

- Historical cryptography unit: Connects cipher concepts to Revolutionary War, Civil War, and Freemasonry

- STEM integration: Combines history, mathematics, and pattern recognition

Pedagogical Advantages:

- Simple enough for elementary students to grasp

- Visually engaging geometric symbols hold attention

- No complex mathematics required

- Historical narratives provide context

- Hands-on encoding/decoding keeps students engaged

Scout Programs

The pigpen cipher maintains long-standing traditions in youth organizations:

Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts:

- Cryptography merit badge activities

- Camp puzzle challenges and scavenger hunts

- Team-building cipher exercises

- Tradition extending back decades in scouting education

These programs introduce cryptographic thinking to young people, with pigpen serving as accessible gateway to more complex systems.

Popular Culture Appearances

Books and Literature

The pigpen cipher appears throughout contemporary fiction and non-fiction:

Dan Brown's "The Lost Symbol" (2009):

- Features Masonic cipher prominently in plot

- Introduced millions of readers to the pigpen/Freemason connection

- Reinforced cultural associations between secret societies and cryptography

Other Literary Appearances:

- Children's books on codes and ciphers (hundreds of titles)

- Mystery novels featuring cipher puzzles

- Young adult adventure series with secret messages

- Educational cryptography textbooks using it as a standard example

Video Games

The pigpen cipher appears as puzzle element in numerous games:

Assassin's Creed II:

- Features "Templar cipher" puzzles using pigpen-style symbols

- Players decipher clues to unlock hidden content

- Connects historical secret society themes to gameplay

Sea of Thieves:

- Treasure map encoding uses pigpen-inspired symbols

- Pirate theme naturally incorporates cipher puzzles

- Community created guides teaching cipher recognition

Other Gaming Appearances:

- Escape room video game puzzle elements

- Hidden message Easter eggs in various titles

- ARG (Alternate Reality Game) components

- Mystery adventure game challenges

Film and Television

While less prominent than in literature and games:

- Background detail in historical dramas featuring Freemasonry

- Puzzle elements in mystery television series

- Documentary programs on cryptography history

- Secret society depictions in various genres

Recreational and Puzzle Uses

Modern Applications

The pigpen cipher flourishes in contemporary recreational contexts:

Escape Rooms:

- Physical escape room puzzles frequently employ pigpen ciphers

- Players decode messages to find clues or unlock compartments

- Theme flexibility (pirates, Masons, secret agents, historical settings)

- Difficulty adjustable through hints or variant configurations

Geocaching:

- Cipher caches require solving pigpen puzzles to find coordinates

- Multi-stage caches use encoded clues

- Community-created cipher challenges

- Educational geocaching activities

Scavenger Hunts and Treasure Trails:

- Birthday party activities for children and adults

- Team-building exercises for organizations

- Educational field trips incorporating cipher clues

- Family game nights and puzzle events

Puzzle Books and Magazines:

- Cryptogram puzzle books include pigpen variants

- Brain teaser collections feature geometric cipher challenges

- Activity books for children incorporate encoding/decoding exercises

Contemporary Subculture Usage

Prison Communication

Modern reports indicate continued pigpen usage in correctional facilities:

- Obscurity-based privacy: Guards unfamiliar with cipher overlook geometric symbols

- Graffiti and notes: Encoded messages on walls, furniture, or passed items

- Tattoos: Pigpen symbols encoding names, affiliations, or personal messages

- No serious security: Detected cipher usage faces punishment

Other Subcultural Contexts:

- Street art and graffiti: Artists incorporating cipher symbols

- Personal journals: Individuals maintaining privacy through encoding

- Secret note-passing: Nostalgic recreation of childhood secret communication

- Fandoms and communities: Groups adopting cipher as shared identifier

These modern uses echo the cipher's historical role: creating boundaries between initiated and uninitiated, signaling group membership, and providing psychological satisfaction of "secret knowledge"—even when actual security remains minimal.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who invented the pigpen cipher?

No single inventor created the pigpen cipher. Its origins trace to ancient Jewish Kabbalah traditions featuring the "Nine Chambers" system for encoding Hebrew letters. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa provided the first clear documented description in 1531 in his "Three Books of Occult Philosophy," describing the Kabbalistic grid-and-dot system. The cipher likely developed independently in various forms across different cultures. Freemasons systematically adopted and popularized it in the 18th century, leading to its common designation as the "Masonic cipher." The system evolved through multiple iterations rather than being invented by a single person.

Why is it called the pigpen cipher?

The name "pigpen cipher" derives from the visual resemblance of the grid symbols to pens or enclosures used to contain pigs on farms. The tic-tac-toe grid compartments look similar to the fenced sections of animal pens. Alternative names include "tic-tac-toe cipher" (for the grid pattern) and "Masonic cipher" (for its association with Freemasons). The agricultural metaphor captured the cipher's compartmentalized structure, where each letter occupies its own geometric "pen" within the grid system.

Is the pigpen cipher secure?

No, the pigpen cipher is not secure by modern cryptographic standards. It functions as a simple monoalphabetic substitution cipher, meaning each letter is always replaced by the same symbol. This makes it highly vulnerable to frequency analysis—the most common symbols correspond to the most common letters in the language (E, T, A, O, etc.). The geometric symbols provide no actual security advantage over letter-based substitution; they only create visual unfamiliarity. Widespread recognition eliminates any security through obscurity. Today it serves purely educational purposes and should never be used for actual security needs.

How did Freemasons use the pigpen cipher?

Freemasons adopted the pigpen cipher systematically in the early 18th century for fraternal privacy rather than military secrecy. They used it extensively for lodge record keeping, correspondence between members, documentation of rituals and ceremonies, and internal organizational communications. The most visible evidence appears on Freemason gravestones and tombstones from the 18th-19th centuries, featuring encoded memorial inscriptions like "Memento Mori" (Remember Death). Examples include Trinity Church Cemetery in New York City and the 1785 Thomas Brierley grave marker. Freemasons also used the cipher on certificates of membership, medals, tokens, and official documents. The association became so strong that "Masonic cipher" remains a common alternative name for the pigpen cipher today.

What are the different pigpen cipher variations?

At least eight documented pigpen cipher variations exist. The standard version uses two tic-tac-toe grids (A-I, J-R with dots) and two X grids (S-V, W-Z with dots). The Rosicrucian variantemploys a single 3×3 grid with 1-3 positional dots per cell. The Newark cipher uses short lines at various angles instead of dots for distinction. The Knights Templar variant (likely 18th century Neo-Templar rather than medieval) features Maltese Cross patterns instead of X shapes. Custom variations include keyword-based alphabets (starting with "MASON" then remaining letters) and randomized letter placements like George Washington's version. Organizations and time periods developed variants to enhance security and establish organizational identity.

When was the pigpen cipher used in American history?

The pigpen cipher saw significant use during two major American conflicts. During the American Revolution (1775-1783), both British forces and the Continental Army employed it for covert communications. George Washington's army documented its use, including a variant with randomized letter placement for enhanced security. During the American Civil War (1861-1865), Union prisoners in Confederate camps used the cipher for secret communications, including messages about camp conditions and escape coordination. Surviving letters and diaries from Civil War prisoners contain pigpen-encoded sections. Beyond military use, American Freemasons adopted the cipher in the 18th century, visible on colonial-era gravestones throughout former colonies.

Conclusion

The pigpen cipher history spans more than 500 years. From mystical roots in pre-1531 Kabbalistic traditions through Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa's 1531 documentation to systematic adoption by Rosicrucians and Freemasons, religious symbolism evolved into the defining fraternal cipher of 18th and 19th century Freemasonry, earning the enduring alternative name "Masonic cipher." Military applications during the American Revolution and Civil War demonstrated practical utility. Notable cases from Olivier Levasseur's legendary treasure to Major Logue's dark diary revealed the cipher's moral neutrality—serving both romantic adventure and concealment of atrocities.

Ready to explore more classical ciphers? Discover the Caesar cipher's fascinating history, learn about other substitution cipher techniques, or try our interactive pigpen cipher decoder tool to practice encoding and decoding messages.

The transformation from practical security tool to educational artifact exemplifies broader patterns in cryptographic history. Mathematical analysis advanced and widespread publication eliminated obscurity. The pigpen cipher lost cryptographic viability. Yet unlike many obsolete systems that faded completely, pigpen experienced remarkable cultural persistence. Its geometric elegance, historical richness, and Masonic mystique ensured continued relevance across changing technological and social landscapes.

Today the pigpen cipher thrives in new contexts. It introduces students to cryptographic concepts, challenges escape room participants, decorates video game puzzles, and maintains subcultural communication traditions. Ciphers can outlive their security value through cultural significance, educational utility, and symbolic power.

The pigpen cipher's journey—from Nine Chambers mysticism to Freemason gravestones to children's puzzle books—reveals fundamental human fascinations. The allure of secret knowledge. The pleasure of pattern recognition. The enduring appeal of transforming ordinary letters into mysterious geometric symbols. While no longer viable for actual security, the pigpen cipher remains a vital cultural artifact, bridging past and present in the ongoing story of human communication and concealment.