In the ancient Hebrew text of the Book of Jeremiah lies one of history's earliest documented uses of encryption. When the prophet wrote "Sheshach" in the 6th century BCE, he employed a cipher system to conceal the word "Babylon" from hostile eyes. This ancient encryption method, known as the Atbash cipher, represents humanity's first systematic attempt to protect sensitive information through alphabet transformation.

The Atbash cipher is one of the oldest known encryption methods, dating back to approximately 500-600 BCE. Developed by Hebrew scribes, it encodes messages in biblical texts by reversing the alphabet - a monoalphabetic substitution technique where the first letter becomes the last, the second becomes second-to-last, and so on. In Jeremiah's writings, "Sheshach" encrypted "Babylon" during a time when writing such prophecies openly could have endangered the prophet.

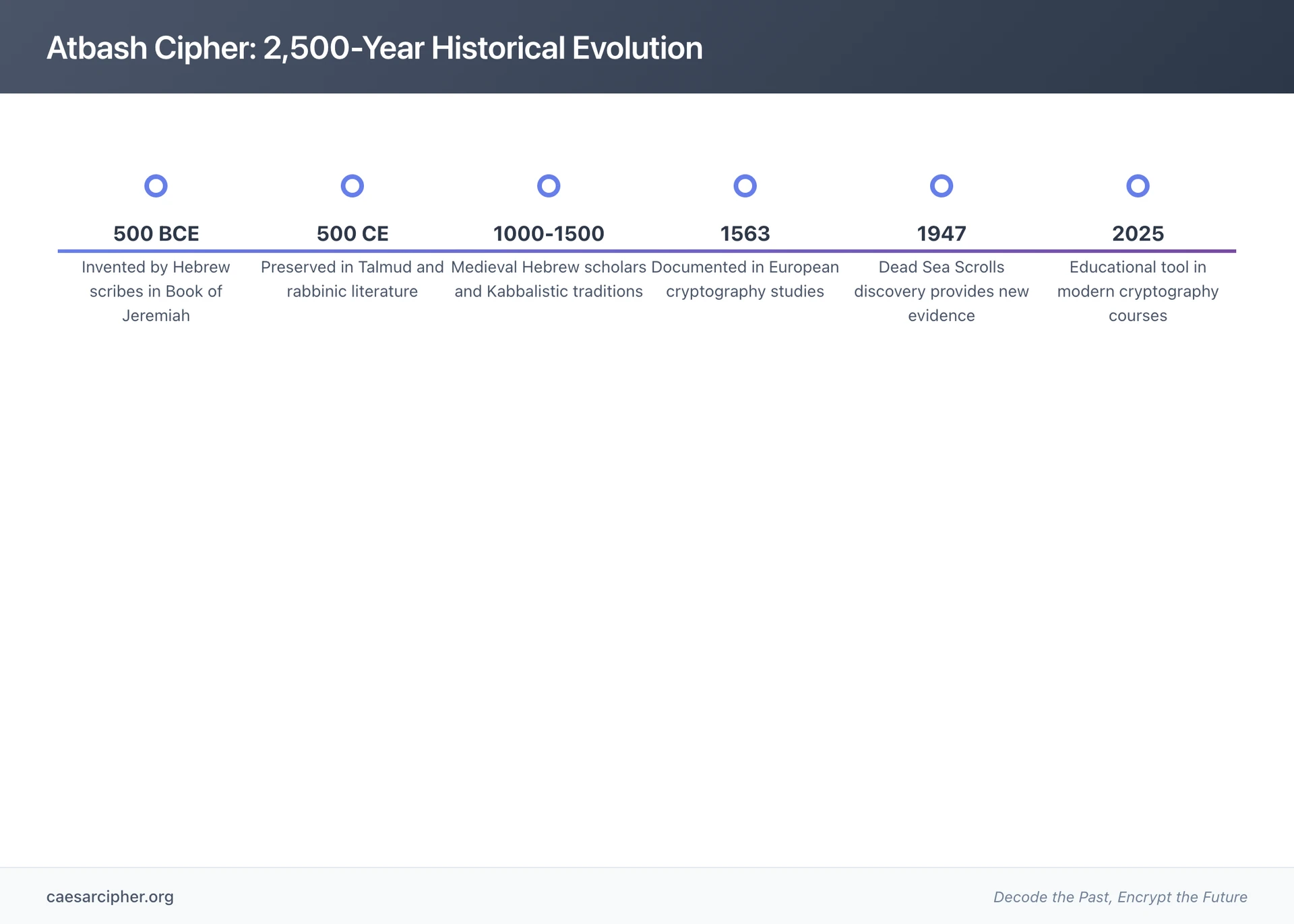

This comprehensive analysis traces the atbash cipher's remarkable 2,500-year journey from ancient Israel through rabbinic traditions, medieval scholarship, and into modern cryptography education. We explore all three documented uses in the Book of Jeremiah, examine archaeological evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls, investigate its cultural evolution, and discover why this ancient technique remains foundational for understanding encryption today.

What is the Atbash Cipher?

Before diving into its fascinating history, let's establish a clear understanding of what the Atbash cipher is and how it works.

Definition

According to Oxford University Humanities Faculty, the Atbash cipher operates by "folding the alphabet in half," creating mirror-image letter pairings. It's a monoalphabetic substitution cipher where the first letter of the alphabet replaces the last, the second replaces the second-to-last, and this pattern continues throughout the entire alphabet.

Atbash requires no separate key. The transformation is fixed and self-inverse: applying Atbash twice returns the original text. In mathematical terms, cryptographers classify it as an affine cipher with parameters a = -1 and b = m-1, where m represents the alphabet length.

Etymology: Why "Atbash"?

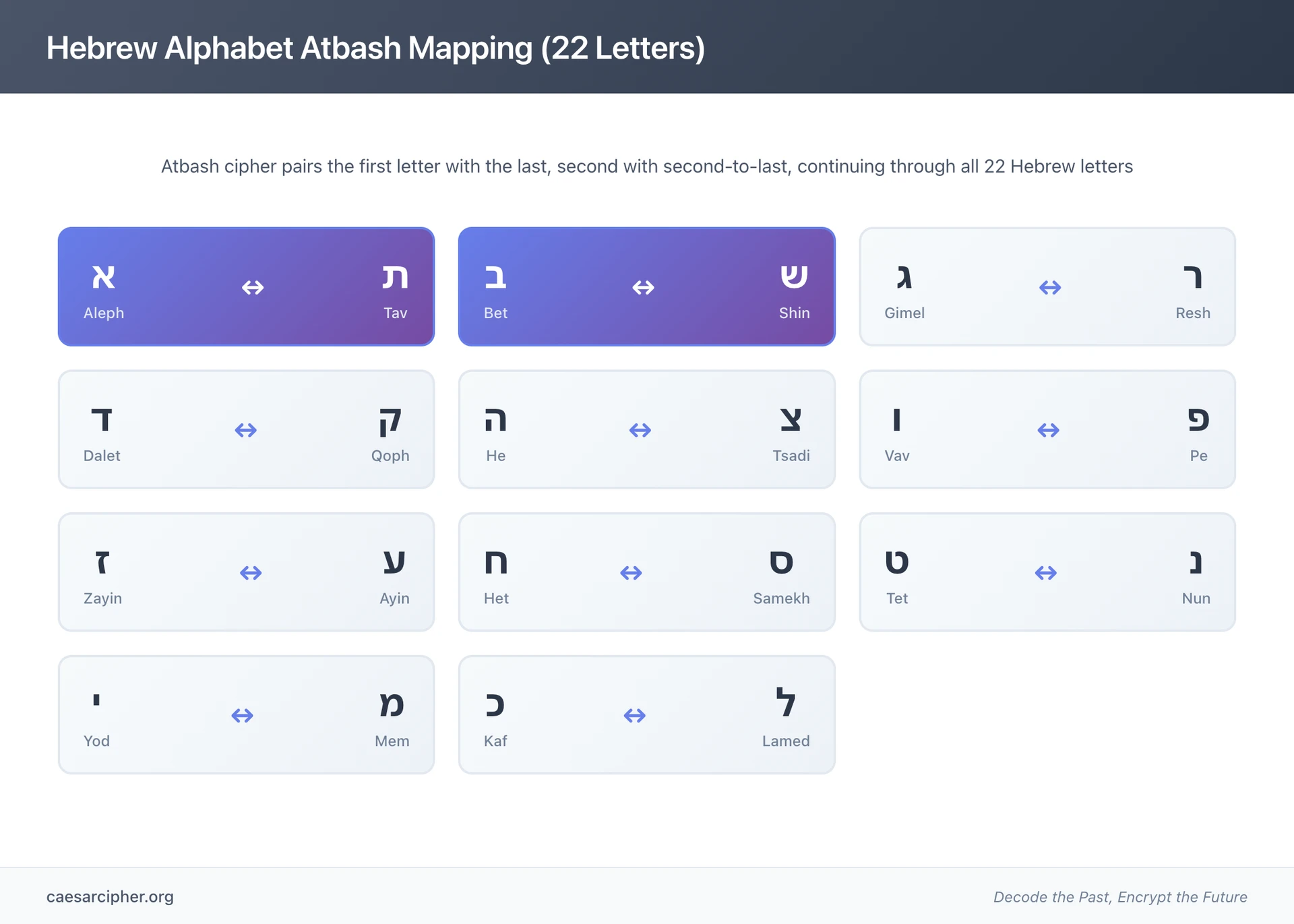

As explained by The Jewish Chronicle, the name "Atbash" comes from the first and last pairs of letters in the Hebrew alphabet: Aleph (א), Tav (ת), Bet (ב), and Shin (ש). The name itself elegantly describes the cipher's mechanism - "At" represents the pairing of Aleph (the first letter) with Tav (the last letter), while "bash" represents Bet (the second letter) paired with Shin (the second-to-last letter).

This naming convention served as a mnemonic device for Hebrew scribes, allowing them to easily remember the substitution pattern. The Hebrew alphabet contains 22 letters, creating 11 paired substitutions in the Atbash system.

How It Works: Quick Overview

The Atbash principle is simple yet effective for its historical context.

Hebrew Alphabet Application (Original):

- א (Aleph) ↔ ת (Tav)

- ב (Bet) ↔ ש (Shin)

- ג (Gimel) ↔ ר (Resh)

- And so on through all 22 letters

English Alphabet Adaptation:

- A ↔ Z

- B ↔ Y

- C ↔ X

- D ↔ W

- E ↔ V

Simple Example:

The English word "HELLO" transforms to "SVOOL":

- H → S

- E → V

- L → O

- L → O

- O → L

This reversal mechanism was accessible to literate scribes while appearing cryptic to those unfamiliar with the system.

Historical Origins: Ancient Hebrew Cryptography (500-600 BCE)

The history of the Atbash cipher begins in one of the most turbulent periods of ancient Israelite history - the 6th century BCE, when the kingdom of Judah faced existential threats from the Babylonian Empire.

Political and Religious Context

Ancient Israel in the 6th century BCE was a small kingdom caught between competing Near Eastern empires. The Babylonian Empire, under Nebuchadnezzar II, emerged as the dominant regional power, conquering Jerusalem in 586 BCE and forcing many Judeans into exile. This political crisis created an environment where prophetic messages predicting Babylon's downfall carried significant danger.

The prophet Jeremiah operated during this period of political sensitivity. His prophecies foretold Jerusalem's fall and eventual judgment upon Babylon itself. Recording such messages in plain text could have endangered Jeremiah, his scribes, and anyone possessing the manuscripts if they fell into Babylonian hands. This context explains why Hebrew scribes employed encryption methods like Atbash.

Religious scribes held special status in ancient Israelite society as the educated elite responsible for preserving and transmitting sacred texts. Their training included mastery of Hebrew language, textual copying techniques, and various literary devices. Atbash emerged from this sophisticated scribal tradition as one tool for handling sensitive or symbolically significant content.

Dating and Archaeological Evidence

The Book of Jeremiah's composition period provides our timeline for Atbash's earliest documented use. Biblical scholars date Jeremiah's prophetic activity to approximately 627-586 BCE, during the reigns of Judah's final kings. The text itself was likely compiled shortly after these events, in the late 7th to early 6th century BCE.

According to the Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security (Springer), Atbash is classified as "one of the earliest monoalphabetic substitution ciphers," with manuscript evidence supporting a date of approximately 500-600 BCE. This makes it potentially the oldest documented cipher system in human history - predating the Roman Caesar cipher by roughly 500 years.

The primary evidence comes not from separate cryptographic manuals but from the biblical manuscripts themselves, where Atbash appears embedded within the prophetic text. This suggests the technique was known and recognized by the scribal community without requiring explicit explanation.

The Invention: Why Reverse the Alphabet?

Why did Hebrew scribes choose alphabet reversal? Several factors contributed to this choice:

Structural Elegance: The Hebrew alphabet's 22-letter structure creates natural symmetry. Reversing it produces exactly 11 letter pairs with no awkward middle letter (unlike the 26-letter English alphabet). This mathematical elegance appealed to scribes trained in textual precision.

Symbolic Significance: In Hebrew prophetic literature, reversal carried symbolic meaning, representing divine judgment, the overturning of power, or the undoing of established order. Using a reversed alphabet to encrypt "Babylon" symbolically represented the reversal of Babylon's power that Jeremiah prophesied.

Memorability: Unlike ciphers requiring variable keys or complex algorithms, Atbash required only knowledge of the alphabet itself. Any trained scribe familiar with the Hebrew alphabet could perform the transformation without additional tools or key storage.

Cultural Context: Ancient Hebrew culture viewed the alphabet as having sacred significance. The first and last letters (Aleph and Tav) appear in Jewish tradition as representing totality: "the beginning and the end." Creating pairings from opposite ends of this sacred structure held special meaning beyond mere encryption.

Earliest Known Documentation

As documented in Sefaria's biblical database, the Book of Jeremiah provides the earliest confirmed evidence of Atbash cipher usage. No earlier texts - from any ancient Near Eastern culture - contain documented cipher systems predating this example. While other ancient civilizations developed various codes and secret writing systems, Jeremiah's use of Atbash represents the oldest systematic alphabet substitution cipher in recorded history with scholarly consensus.

This historical priority has made Atbash a foundational example in cryptography education. When students learn about the evolution of encryption, they typically encounter Atbash as humanity's first documented step toward systematic cryptographic thinking.

Biblical Usage: The Book of Jeremiah

The biblical Book of Jeremiah contains the most famous and thoroughly documented examples of atbash cipher usage in ancient texts. These instances provide not only historical evidence of early encryption but also insight into the practical and symbolic purposes of cryptography in the ancient world.

Overview: Why Jeremiah Used Encryption

During the late 7th and early 6th centuries BCE, the prophet Jeremiah delivered messages that placed him in danger. His prophecies predicted Jerusalem's fall to Babylon, called for submission to Babylonian rule, and foretold eventual divine judgment upon Babylon itself. Recording such prophecies in writing created permanent, potentially incriminating evidence.

Biblical scholars debate Jeremiah's motivations for using Atbash. Some argue the encryption served practical protection, concealing prophetic judgments from Babylonian authorities who might persecute the prophet or destroy the manuscripts. Others suggest primarily symbolic purposes, where reversing Babylon's name represented the reversal of its power in divine judgment. A third perspective views Atbash as a conventional scribal practice for handling politically sensitive content.

The actual motivation likely combined practical and symbolic elements. The cipher was simple enough that educated Hebrew readers could decode it, suggesting its purpose was a layer of discretion and symbolic meaning rather than absolute secrecy.

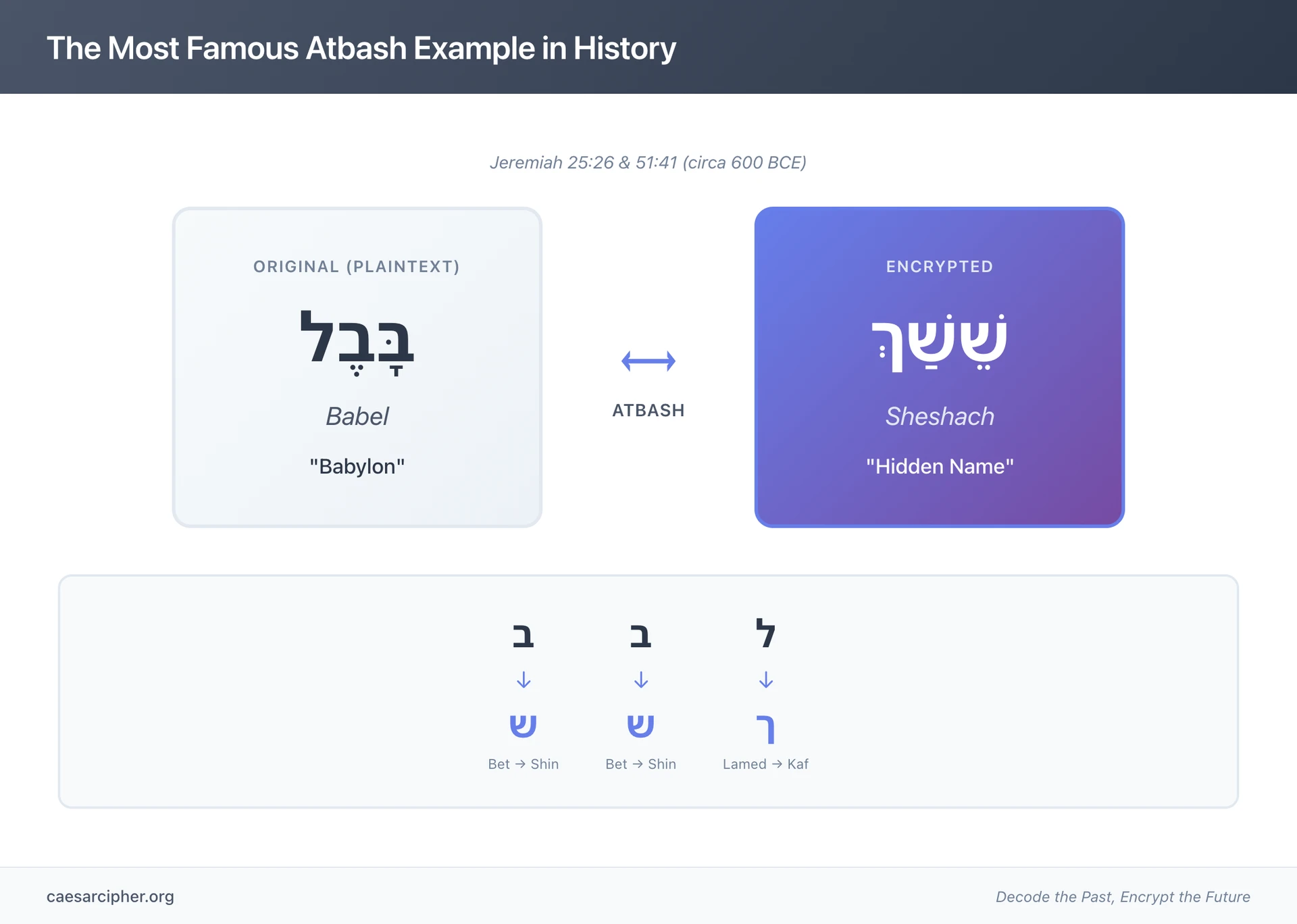

Case Study 1: Jeremiah 25 - Sheshach = Babylon

The most famous example of Atbash cipher in history appears in Jeremiah 25

. The verse, in context, lists nations that will drink from the cup of God's wrath, concluding with: "and the king of Sheshach shall drink after them."Hebrew Text Analysis:

According to Sefaria's biblical database, the Hebrew text reads "Sheshach" (שֵׁשַׁךְ), which through Atbash transformation becomes "Babel" or "Babylon" (בָּבֶל). The transformation works letter by letter in the Hebrew alphabet:

- ש (Shin) → ב (Bet)

- ש (Shin) → ב (Bet)

- ך (Final Kaf) → ל (Lamed)

Result: שֵׁשַׁךְ (Sheshach) → בָּבֶל (Babel/Babylon)

Historical Significance:

This encrypted name appears in a passage listing nations facing divine judgment, with Babylon - the instrument of judgment against other nations - itself ultimately subject to judgment. The encryption adds layers of meaning: Babylon's name is literally reversed, symbolically representing the reversal of its power.

Early biblical commentators recognized this cipher. The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) documented scholarly consensus about this interpretation, noting that "Sheshach" appears nowhere else as a geographical name, making the Atbash explanation compelling. The Encyclopedia Britannica's 9th edition (1880s) similarly acknowledged this famous cryptographic example.

Scholarly Interpretations:

Modern biblical scholarship offers several perspectives:

-

Protection Theory: If Babylonian officials could read Hebrew, encrypting Babylon's name provided minimal protection from casual inspection while remaining readable to the intended Hebrew audience.

-

Symbolic Theory: The reversal itself constitutes a prophetic statement. Babylon's power, seemingly absolute, will be overturned. The cipher performs the reversal it predicts.

-

Scribal Convention Theory: Atbash may have been standard practice for writing sensitive names, similar to how modern writers use asterisks or euphemisms for controversial terms.

-

Composite Theory: Multiple purposes likely coexisted: practical discretion, symbolic meaning, and scribal convention reinforcing each other.

Case Study 2: Jeremiah 51 - Lev-kamai = Chaldea

The second confirmed Atbash instance appears in Jeremiah 51

, which begins: "Thus says the Lord: Behold, I am stirring up the spirit of a destroyer against Babylon, against the inhabitants of Lev-kamai."Hebrew Text Analysis:

As documented in Sefaria, "Lev-kamai" (לֵב קָמַי) represents an Atbash encryption of "Kasdim" (כַּשְׂדִּים) - the Hebrew term for Chaldea or Chaldeans, referring to the Babylonian Empire's ruling people.

The Hebrew phrase "Leb-kamai" literally translates as "heart of my adversaries," which provides an additional layer of meaning beyond the simple geographic reference. Scholarly consensus identifies this as Atbash for Chaldea, though the letter-by-letter transformation is more complex than the Sheshach example due to the multi-word Hebrew construction.

Significance:

This second instance demonstrates systematic rather than isolated Atbash usage in Jeremiah. The fact that the prophet (or his scribes) employed this technique multiple times suggests it was an established method within their textual practice, not a one-time encryption experiment.

Interestingly, Jeremiah 51 also contains plain references to Babylon and Chaldea alongside the encrypted versions, raising questions about the cipher's purpose. If absolute secrecy were the goal, mixing encrypted and plain text would be counterproductive. This supports the symbolic and scribal convention theories over pure secrecy motivations.

Case Study 3: Jeremiah 51 - Sheshach Returns

Jeremiah 51

contains the second appearance of "Sheshach," creating a parallel with Jeremiah 25:26: "How Sheshach is taken, the praise of the whole earth seized! How Babylon has become a horror among the nations!"Significance of Repetition:

The reuse of "Sheshach" in a different chapter reinforces several conclusions:

-

Intentional Pattern: The repetition demonstrates deliberate, systematic use rather than textual error or scribal accident.

-

Bookend Structure: Sheshach appears in both an earlier prophecy (chapter 25) and a later, more detailed oracle against Babylon (chapter 51), creating a literary frame around Jeremiah's Babylon prophecies.

-

Mixed Usage: Chapter 51 uses both "Sheshach" (verse 41) and plain "Babylon" (verses 1, 6, 8, and others), suggesting the cipher served rhetorical variety or emphasis rather than consistent concealment.

Scholarly Debate:

Biblical scholars discuss whether all Atbash instances originated with Jeremiah himself or whether some represent later scribal additions. The parallel structure between 25

and 51 suggests intentional literary composition rather than random insertion. The consistent use of the same encrypted term ("Sheshach" for Babylon in two places, "Leb-kamai" for Chaldea once) indicates a systematic approach.Modern Biblical Scholarship

Contemporary biblical studies continue exploring these Atbash instances from multiple angles:

Textual Criticism: Scholars examine ancient manuscripts to confirm the consistency of these readings across different textual traditions. The Dead Sea Scrolls and Septuagint (Greek translation) provide comparative evidence.

Historical Context Research: Understanding the political circumstances when Jeremiah wrote helps scholars evaluate different theories about the cipher's purpose. Archaeological findings about Babylonian governance inform these discussions.

Linguistic Analysis: Hebrew language specialists analyze the grammatical construction and literary context of these encrypted terms, examining how they function within the larger prophetic poetry.

Comparative Studies: Researchers compare Jeremiah's Atbash usage with encryption practices in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, searching for parallels or unique features that illuminate Hebrew scribal practices.

Religious and Philosophical Implications: Theologians explore what these ciphers reveal about prophecy, divine communication, and the nature of sacred texts, asking whether encryption itself carries theological significance in prophetic literature.

The consensus among mainstream biblical scholars affirms that these three instances represent genuine ancient Atbash usage, making them invaluable evidence for the early history of cryptography.

Dead Sea Scrolls Connection

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947 opened new windows into ancient Hebrew textual practices, including potential connections to the Atbash cipher tradition.

Discovery Context

Between 1947 and 1956, Bedouin shepherds and archaeologists discovered approximately 900 documents in caves near Qumran, on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea. These manuscripts, dating from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE, represent the oldest surviving biblical manuscripts and provide unprecedented insight into Jewish religious practices during the Second Temple period.

The scrolls include biblical texts, sectarian community documents, apocryphal works, and various other writings. Their dating spans roughly six centuries, covering the period from late biblical times through the era when Christianity emerged. For cryptography historians, these manuscripts offer evidence of how Hebrew scribal communities handled texts during the centuries after Jeremiah but before the Talmudic period.

Hugh Schonfield's Groundbreaking Research

Hugh Joseph Schonfield (1901-1988) was a British biblical scholar who made controversial contributions to Dead Sea Scrolls research. While primarily known for his unorthodox historical Jesus theories, Schonfield also investigated textual encryption in ancient Hebrew documents.

In his research on the scrolls, Schonfield identified what he argued were Atbash cipher instances within the Qumran texts. His most discussed example involved the term "Hagu" which, through Atbash transformation, becomes "Tsaraph" (meaning "tested" or "refined"). He connected this to the scroll's reference to the "Teacher of Righteousness" - a mysterious figure central to the Qumran community's identity.

Schonfield's theories generated significant academic debate. Some scholars found his cryptographic analysis intriguing and worth further investigation, while others criticized his methodology as reading cipher patterns into texts where simpler explanations existed.

Academic Reception:

The scholarly community's response to Schonfield's Dead Sea Scrolls cipher theories remains mixed.

Supporters argue that given the confirmed Atbash usage in Jeremiah, finding similar practices in later Hebrew texts is plausible. The Qumran community was known for esoteric textual practices, making encryption consistent with their documented behavior.

Critics point out that identifying Atbash requires careful linguistic analysis. Not every unusual Hebrew term or spelling necessarily represents encryption. The danger of "seeing patterns" where none exist is significant in cryptographic analysis.

Moderate Position: Most contemporary scholars acknowledge Atbash as part of the Hebrew scribal toolkit available during the Second Temple period but emphasize that each claimed instance requires rigorous case-by-case verification.

Atbash in Qumran Texts

Research from the University of Kentucky on Dead Sea Scrolls textual systems confirms that the Aramaic square script used in these documents employed the same Hebrew alphabet underlying Atbash. The writing system remained consistent from Jeremiah's era through the Qumran period, making Atbash technically feasible.

However, as scholars emphasize, establishing that Atbash could be used differs from proving it was used in specific cases. The sectarian nature of the Qumran community - with evidence of special vocabulary, symbolic number systems, and esoteric textual interpretation - suggests an environment where encryption might be employed, but concrete proof requires more than possibility.

Transparency Note: While Atbash's presence in Dead Sea Scrolls is discussed through Hugh Schonfield's research and other scholarly analysis, experts emphasize that each claimed instance requires careful case-by-case examination with solid linguistic evidence. Not all cryptic or unusual texts in the scrolls are necessarily Atbash, and the extent of its usage remains subject to ongoing research and scholarly debate.

Modern Scholarship and Ongoing Research

Current research on potential Atbash usage in Second Temple period texts continues through several approaches:

Digital Textual Analysis: Modern computational tools allow researchers to systematically search ancient Hebrew texts for statistical patterns consistent with Atbash usage, potentially identifying instances human readers might miss.

Comparative Manuscript Studies: Examining variations between different scrolls and textual traditions can reveal whether certain terms were consistently written in ways suggesting intentional encoding.

Linguistic Context Analysis: Understanding the full linguistic environment of Second Temple Hebrew - including wordplay, literary devices, and scribal conventions - helps distinguish encryption from other textual practices.

Archaeological Context: New manuscript discoveries and improved dating techniques continue to expand evidence about Second Temple period scribal practices, potentially illuminating how widespread Atbash or similar techniques were.

The Dead Sea Scrolls connection remains an active research area, demonstrating how ancient cryptographic practices continue to fascinate modern scholars and reveal layers of meaning in historical texts.

Evolution Through History

The remarkable survival of Atbash cipher knowledge across 2,500 years demonstrates the power of cultural transmission through religious and scholarly traditions. Unlike most ancient ciphers that disappeared into historical obscurity, Atbash maintained continuous recognition from biblical times to the present day.

Rabbinic Tradition

Following the biblical period, Atbash continued to appear in rabbinic literature as both an exegetical tool and a textual curiosity worthy of scholarly discussion.

The Talmud, compiled approximately 500 CE, includes discussions of letter manipulation techniques used for various interpretive and mnemonic purposes. According to Sefaria's Talmud collection, Shabbat 104a discusses letter sequences and substitution methods in the context of teaching and remembering the Hebrew alphabet. While not primarily focused on cryptography, these discussions preserved knowledge of Atbash as part of the rabbinic scholarly toolkit.

Medieval rabbinic commentators frequently noted the Atbash instances in Jeremiah, ensuring each generation of scholars recognized these encrypted terms. Commentaries by Rashi (11th century), Ibn Ezra (12th century), and other influential rabbis explicitly identified "Sheshach" as Atbash for Babylon, transmitting this knowledge through the Jewish educational system.

The rabbinic approach treated Atbash as one among many hermeneutical techniques - methods for deriving additional meaning from biblical texts. This broader context of textual interpretation ensured Atbash remained known even without practical encryption applications.

Medieval Usage

During the medieval period (roughly 500-1500 CE), Hebrew scholars across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East continued preserving Atbash knowledge through their textual studies.

Kabbalistic Connections:

Medieval Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah) developed elaborate systems for interpreting sacred texts through letter manipulation, numerical values (gematria), and symbolic correspondences. While Kabbalah emphasized spiritual rather than cryptographic meanings, its practitioners necessarily maintained familiarity with techniques like Atbash.

Kabbalistic texts occasionally employed Atbash-like transformations for symbolic purposes - representing spiritual inversions, hidden divine names, or mystical correspondences. These uses diverged from Jeremiah's apparent encryption purpose but kept the technical method alive within esoteric Jewish scholarship.

Scholarly Transmission:

Jewish communities maintained sophisticated educational institutions throughout the medieval period. Torah study, Talmud analysis, and Hebrew language mastery formed the core curriculum. Within this educational framework, discussions of the Jeremiah cipher examples ensured literate community members learned about Atbash.

This preservation through religious education explains why Atbash survived when most ancient ciphers disappeared. Without religious texts to preserve them, classical Roman and Greek encryption methods largely vanished from historical memory until modern scholars reconstructed them from fragmentary references.

Renaissance and Early Modern Period

The Renaissance (15th-17th centuries) marked the beginning of systematic cryptography study in Europe. As scholars developed more sophisticated encryption methods, they also investigated historical precedents for secret writing.

When European intellectuals began studying Hebrew texts and Jewish scholarly traditions more extensively, they encountered Atbash as an ancient cipher example. Early modern works on cryptography, such as Giovanni Battista della Porta's De Furtivis Literarum Notis (1563) and later works, sometimes mentioned biblical ciphers including Atbash.

However, by this period, cryptographers had developed far more sophisticated techniques:

- Polyalphabetic ciphers (like the Vigenère cipher, 16th century) using multiple substitution alphabets

- Nomenclators combining code lists with cipher systems

- Steganography techniques for hiding message existence entirely

Against these developments, Atbash appeared primitive. Its primary value shifted from practical application to historical interest - representing humanity's early cryptographic attempts rather than a useful modern technique.

Modern Era

In the 19th and 20th centuries, as cryptography became a serious academic discipline and military priority, historians systematically documented the evolution of encryption methods. Atbash earned recognition as potentially the oldest documented cipher in history.

Educational Applications:

Today, Atbash serves primarily educational purposes:

-

Introductory Cryptography: Computer science and cybersecurity courses use Atbash to introduce students to substitution cipher concepts before progressing to more complex systems.

-

Historical Context: Cryptography history courses present Atbash as the starting point for tracing encryption evolution from ancient times through modern computational methods.

-

Biblical Studies: Seminary programs and religious studies courses teach Atbash when analyzing the Book of Jeremiah and Hebrew textual practices.

-

Recreational Cryptography: Puzzle books, escape rooms, and recreational codebreaking communities sometimes incorporate Atbash for its simplicity and historical interest.

Pop Culture References:

Atbash occasionally appears in popular media involving codes and ciphers - mystery novels, films, television shows, and video games sometimes reference this ancient technique when creators want historical depth or religious symbolism.

Cultural Preservation:

Jewish educational institutions continue teaching about Atbash as part of broader Hebrew language and biblical studies, maintaining the unbroken transmission that has persisted for 2,500 years.

Why Did Atbash Survive 2,500 Years?

Several factors explain this remarkable longevity:

Religious Preservation: Embedding Atbash in sacred texts (Jeremiah) ensured continuous study and transmission. Religious communities preserved ancient knowledge that secular history might have lost.

Simplicity and Memorability: The straightforward reversal principle requires no complex instructions or external keys. Anyone knowing the Hebrew alphabet could understand Atbash.

Educational Value: Atbash's simplicity makes it perfect for teaching basic cryptographic concepts - demonstrating substitution ciphers, discussing security weaknesses, and illustrating historical encryption development.

Cultural Significance: The connection to biblical prophecy, Jewish tradition, and ancient history gives Atbash cultural meaning beyond mere cryptographic technique.

Continuous Documentation: Each generation of scholars wrote about Atbash, creating an unbroken chain of documentation from ancient commentaries through medieval texts to modern academic works.

This combination of religious, cultural, educational, and historical factors transformed Atbash from a potentially forgotten ancient technique into a permanently preserved piece of human intellectual heritage.

How the Atbash Cipher Works: Technical Explanation

Understanding Atbash's technical mechanism clarifies why it was useful in ancient contexts while being completely insecure by modern standards.

The Reverse Alphabet Principle

Atbash operates on an elegantly simple principle: create a one-to-one mapping between each alphabet letter and its positional opposite.

Hebrew Alphabet Implementation (22 letters):

The original Hebrew version works with 22 consonantal letters:

- Position 1: א (Aleph) ↔ Position 22: ת (Tav)

- Position 2: ב (Bet) ↔ Position 21: ש (Shin)

- Position 3: ג (Gimel) ↔ Position 20: ר (Resh)

- Position 4: ד (Dalet) ↔ Position 19: ק (Qoph)

- Position 5: ה (He) ↔ Position 18: צ (Tsadi)

- Position 6: ו (Vav) ↔ Position 17: פ (Pe)

- Position 7: ז (Zayin) ↔ Position 16: ע (Ayin)

- Position 8: ח (Het) ↔ Position 15: ס (Samekh)

- Position 9: ט (Tet) ↔ Position 14: נ (Nun)

- Position 10: י (Yod) ↔ Position 13: מ (Mem)

- Position 11: כ (Kaf) ↔ Position 12: ל (Lamed)

English Alphabet Adaptation (26 letters):

The same principle applies to English with its 26-letter alphabet:

A↔Z, B↔Y, C↔X, D↔W, E↔V, F↔U, G↔T, H↔S, I↔R, J↔Q, K↔P, L↔O, M↔N

Notice that with an even number of letters (26), there's no single center letter - M and N form the middle pair.

Worked Examples

Example 1: Simple English Word

Plaintext: "CODE"

- C → X (position 3 → position 24)

- O → L (position 15 → position 12)

- D → W (position 4 → position 23)

- E → V (position 5 → position 22)

Ciphertext: "XLWV"

Example 2: English Sentence

Plaintext: "HELLO WORLD"

- H → S

- E → V

- L → O

- L → O

- O → L

- (space preserved)

- W → D

- O → L

- R → I

- L → O

- D → W

Ciphertext: "SVOOL DLIOW"

Example 3: Historical Hebrew Example

Using the famous Jeremiah instance:

Hebrew Plaintext: בָּבֶל (Babel/Babylon)

- ב (Bet, position 2) → ש (Shin, position 21)

- ב (Bet, position 2) → ש (Shin, position 21)

- ל (Lamed, position 12) → כ/ך (Kaf, position 11)

Hebrew Ciphertext: שֵׁשַׁךְ (Sheshach)

This transformation demonstrates the actual biblical usage that preserved Atbash for posterity.

Encryption = Decryption (Symmetric Nature)

Atbash possesses a mathematically elegant property: it's self-inverse. Applying the transformation twice returns the original text.

Demonstration:

- Start: "HELLO"

- Apply Atbash once: "SVOOL"

- Apply Atbash again to "SVOOL":

- S → H

- V → E

- O → L

- O → L

- L → O

- Result: "HELLO" (back to original)

Practical Implication:

Encryption and decryption use exactly the same process. No separate "key" exists. The transformation itself serves as both encryption and decryption method. This simplicity made Atbash easy for ancient scribes to use but also contributes to its security weakness.

Mathematical Relationship:

For those interested in the formal mathematics, Atbash can be expressed as an affine cipher with parameters a = -1 (or equivalently, a = m-1 where m is alphabet size) and b = m-1. This classification connects it to the broader family of monoalphabetic substitution ciphers studied in modern cryptography courses.

Is the Atbash Cipher Secure?

Understanding Atbash's security properties reveals why it served ancient purposes while being completely inadequate for modern encryption needs.

Direct Answer

No, the Atbash cipher is not secure by modern cryptographic standards. It has no secret key, making it a very weak monoalphabetic substitution cipher that can be easily broken using frequency analysis or simple pattern recognition. While it served symbolic and limited security purposes in ancient times (500 BCE), modern encryption methods like AES and RSA are necessary for actual security today.

Weaknesses and Vulnerabilities

1. No Key Space:

Modern ciphers derive security from key space - the number of possible keys an attacker must try. AES-256, for example, has 2^256 possible keys (an astronomically large number). Atbash has exactly one possible transformation - the reversal mapping. No key exists to guess or brute-force; simply knowing the method means knowing the complete cipher.

2. Monoalphabetic Substitution Vulnerability:

Atbash belongs to the monoalphabetic substitution cipher family, where each plaintext letter always maps to the same ciphertext letter. This consistency creates exploitable patterns:

Frequency Analysis Attack:

- English letter "E" appears most frequently in normal text (~13%)

- In Atbash English ciphertext, "V" (which encrypts "E") will appear most frequently

- Analyzing letter frequencies in ciphertext reveals the substitution pattern

- With sufficient ciphertext (typically 20-30 words), frequency analysis can break Atbash in minutes

Pattern Recognition:

- Common English words have recognizable patterns even when encrypted

- "THE" becomes "GSV" - a recognizable three-letter pattern

- Double letters remain double: "HELLO" → "SVOOL" preserves the double-L pattern

- Word length remains unchanged, providing structural clues

3. Trivially Breakable by Modern Standards:

With computational tools:

- A computer program can test Atbash decryption instantly (one operation)

- No computational security exists - knowing the algorithm means immediate decryption

- Even manual cryptanalysis can break Atbash in minutes with basic frequency tables

Historical vs. Modern Security

Why Atbash Worked in 500 BCE:

Context explains why ancient Hebrew scribes found Atbash useful:

-

Literacy Rates: In 6th century BCE, literacy was rare. Most people couldn't read at all, providing a baseline security layer before encryption even begins.

-

Cipher Concept Unknown: The idea of systematic alphabet substitution was novel. Even literate individuals unfamiliar with cipher systems wouldn't recognize encrypted text.

-

Limited Distribution: Manuscripts were expensive, hand-copied documents with limited distribution. Atbash needed to resist casual discovery by the occasional literate Babylonian official, not widespread cryptanalysis.

-

Political Context Value: Even weak encryption provided value. If a Babylonian official glanced at "Sheshach" without deep analysis, they might not recognize it as "Babylon," achieving the prophet's immediate purpose.

-

Symbolic Purpose Primary: If Jeremiah used Atbash primarily for symbolic rather than security purposes (representing Babylon's reversal), actual security strength becomes secondary.

Modern Comparison:

Contemporary encryption operates in a completely different threat environment:

- AES (Advanced Encryption Standard): 128, 192, or 256-bit keys; computationally infeasible to break; used for secure communications and encrypted storage

- RSA: Public-key cryptography enabling secure communication between parties without prior key exchange; forms the basis of internet security

- Modern Standards: Assume adversaries have unlimited computational resources and complete knowledge of encryption algorithms; security relies solely on key secrecy

Against these standards, Atbash offers zero security. Its value today is purely educational, demonstrating fundamental cipher concepts and the evolution from ancient to modern cryptographic thinking.

Educational Value:

Despite complete insecurity, Atbash remains valuable for teaching:

- How substitution ciphers work conceptually

- Why monoalphabetic substitution is weak (frequency analysis demonstration)

- Historical context for cryptography evolution

- The importance of key space in modern security

- How ancient peoples approached information protection

Atbash Cipher vs. Other Substitution Ciphers

Understanding Atbash's place among substitution ciphers illuminates both its unique features and its limitations compared to other classical encryption methods.

Atbash vs. Caesar Cipher

The Caesar cipher, attributed to Julius Caesar in the 1st century BCE, represents the most famous classical cipher alongside Atbash. Despite similarities, key differences distinguish them.

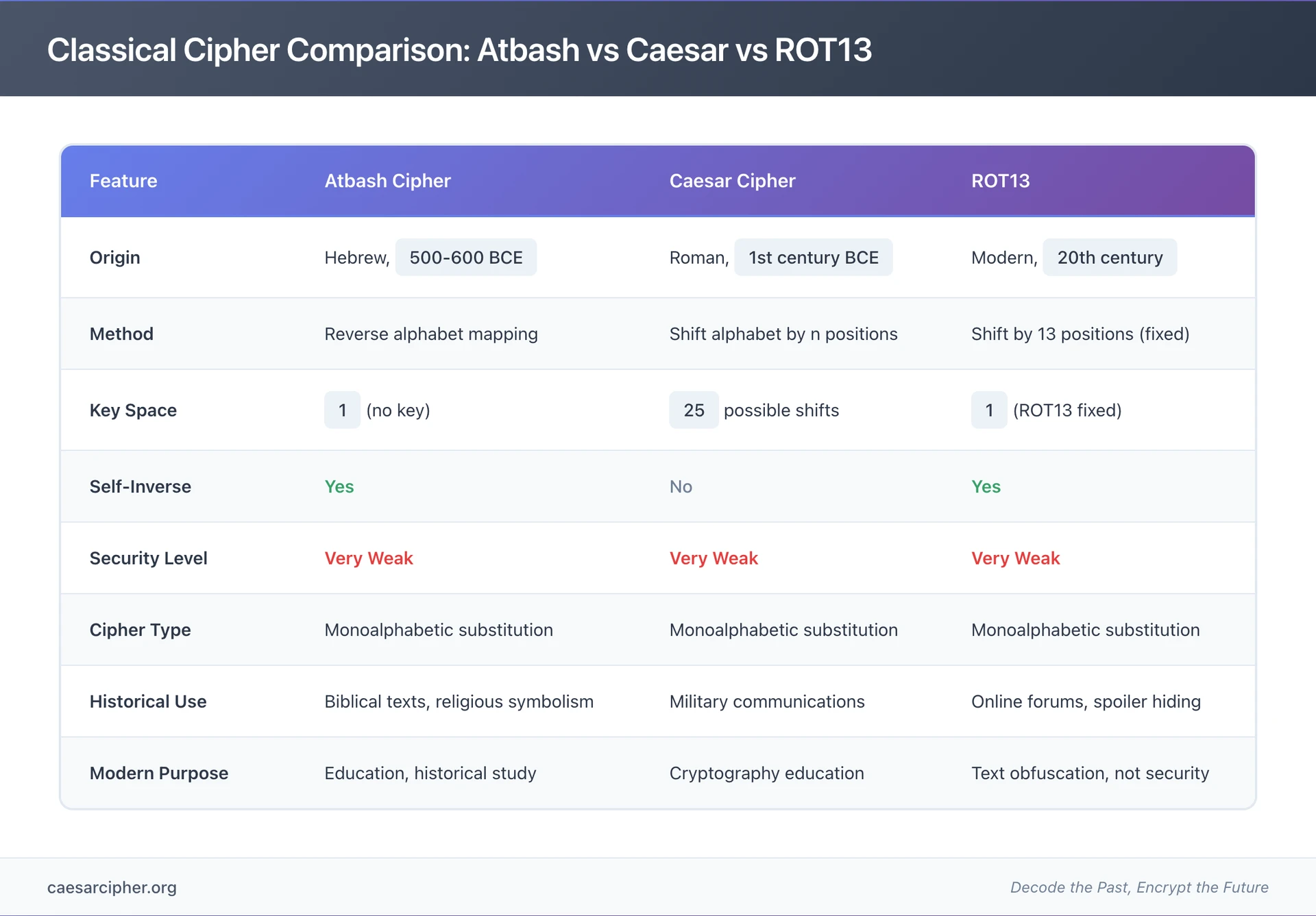

| Feature | Atbash Cipher | Caesar Cipher |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Hebrew, 500-600 BCE | Roman, 1st century BCE |

| Historical Priority | Approximately 500 years earlier | Later development |

| Key | None (fixed reversal) | Shift value (1-25 positions) |

| Possible Keys | 1 (only reversal) | 25 (for English; 21 for Latin) |

| Key Space | No security from keys | Minimal security (easily brute-forced) |

| Method | Reverse alphabet mapping | Shift alphabet by n positions |

| Self-Inverse | Yes (encrypt = decrypt) | No (shift forward ≠ shift backward) |

| Security Level | Very low (one possibility) | Very low (25 possibilities) |

| Historical Use | Biblical texts, religious symbolism | Military communications, political messages |

| Cultural Context | Hebrew scribal/prophetic tradition | Roman military/administrative practice |

| Modern Use | Education, historical study | Education, introductory cryptography |

Historical Context Comparison:

The approximately 500-year gap between Atbash's documented use (6th century BCE) and Caesar's reported cipher usage (1st century BCE) makes Atbash potentially humanity's first systematic cipher. However, different cultural origins and purposes distinguish them.

Atbash: Emerged from Hebrew scribal traditions within a religious and literary context. Its use in prophetic texts suggests purposes beyond pure secrecy: symbolic meaning, rhetorical device, or reverent handling of sensitive content.

Caesar Cipher: Developed within Roman military culture for practical battlefield communications. Ancient historians report Julius Caesar used a shift cipher (typically shift-by-3) for military messages where speed and basic security mattered more than sophisticated encryption.

Security Comparison:

While both ciphers are weak by modern standards, Caesar cipher offers marginally more security than Atbash.

Caesar: An attacker not knowing the shift value must try up to 25 possibilities (for English alphabet). Trivial for modern computers but requiring some effort for manual cryptanalysis.

Atbash: Only one possibility exists. No key means no security from key uncertainty.

Frequency analysis breaks both ciphers equally effectively, but Caesar's key space (however small) provides minimal additional protection.

Atbash vs. ROT13

ROT13 represents a modern variant of the Caesar cipher with an interesting relationship to Atbash:

ROT13 Characteristics:

- Shift cipher with fixed 13-position rotation

- Designed for 26-letter English alphabet

- Self-inverse like Atbash (applying ROT13 twice returns original)

- Used for modern text obfuscation rather than security

Similarities to Atbash:

- Both are self-inverse (encryption = decryption)

- Both use fixed transformations (no variable key)

- Both provide obfuscation rather than true security

- Both have exactly one possible transformation

Differences:

- ROT13 shifts alphabet by fixed amount; Atbash reverses it

- ROT13 designed for modern English; Atbash for ancient Hebrew

- ROT13 for intentionally weak obfuscation (spoilers, email addresses); Atbash had serious purposes in its historical context

Modern ROT13 Usage:

- Online forums use ROT13 to hide spoilers (preventing accidental reading)

- Email harvesters deterred by ROT13-encoded addresses (minimal protection)

- Puzzle games and recreational cryptography

- Clear indicator that real security is not intended

While functionally similar in their simplicity and self-inverse properties, Atbash carries significantly more historical and cultural weight than ROT13's purely practical modern applications.

Place in Cryptography History

Atbash occupies a foundational position in the broader evolution of encryption methods:

Monoalphabetic Substitution Cipher Family:

Atbash represents the simplest form of monoalphabetic substitution, where each plaintext letter consistently maps to one ciphertext letter. This family includes:

- Atbash (reversal) - simplest form

- Caesar cipher (rotation) - slight variation

- Affine cipher (mathematical transformation) - generalized form

- Keyword cipher (keyword-based mapping) - more complex monoalphabetic form

Evolution to Stronger Ciphers:

Cryptographers gradually developed more sophisticated methods to address monoalphabetic vulnerabilities.

Polyalphabetic Ciphers (16th century): Vigenère cipher and others used multiple substitution alphabets, changing which alphabet encodes each letter based on a keyword. This defeated simple frequency analysis.

Transposition Ciphers (various eras): Rearranging letter positions rather than substituting letters created different security properties.

Composite Systems (19th-20th century): Combining substitution and transposition (like ADFGVX cipher) increased security significantly.

Machine Ciphers (20th century): Enigma machine and other electromechanical devices automated complex encryption.

Modern Cryptography (1970s-present): Computational algorithms (DES, AES, RSA) based on mathematical problems provide security even against adversaries with vast computational resources.

Educational Foundation:

Despite obsolescence for actual security, Atbash and related simple ciphers remain valuable for teaching fundamental concepts.

Substitution Principle: Understanding that letters can systematically represent other letters

Frequency Analysis: Demonstrating how statistical properties betray simple ciphers

Key Space Importance: Showing why having only one possible key provides no security

Historical Evolution: Tracing how human cryptographic thinking developed from simple to complex

Cultural Context: Illustrating how different societies approached secret communication

In introductory cryptography courses worldwide, students typically encounter Atbash early as a simple, historically significant example before progressing to more sophisticated systems. This educational role ensures Atbash remains known even though its practical cryptographic value ended centuries ago.

Frequently Asked Questions About Atbash Cipher

When was the atbash cipher invented?

The Atbash cipher was invented around 500-600 BCE by ancient Hebrew scribes. Its earliest documented usage appears in the biblical Book of Jeremiah, where it was used to encrypt place names like "Sheshach" (meaning Babylon) and "Leb-kamai" (meaning Chaldea). This makes Atbash one of the oldest known cipher systems in recorded history, predating the Roman Caesar cipher by approximately 500 years. The exact inventor is unknown, as it emerged from Hebrew scribal traditions rather than a single identifiable creator. The technique was likely developed within the educated scribal class responsible for maintaining religious and prophetic texts during the late First Temple or early Second Temple period. See the Historical Origins section for complete details about the political and cultural context that gave rise to this ancient encryption method.

Who invented the atbash cipher?

The specific inventor of the Atbash cipher is unknown. It was developed by ancient Hebrew scribes as part of their scholarly and religious traditions around 500-600 BCE. Unlike modern ciphers with documented creators, Atbash emerged organically within Hebrew scribal communities during a period of political turmoil when the prophet Jeremiah was active. The earliest known practitioner was likely the prophet Jeremiah himself or his scribes, who used it in biblical texts to encrypt politically sensitive names during the Babylonian conquest of Judah. The cipher reflects collective Hebrew scribal knowledge rather than a single inventor's innovation. This anonymous development is typical of ancient techniques that evolved within specialized professional communities - in this case, the educated scribal class responsible for preserving sacred texts and prophetic messages.

Why is it called "atbash"?

The name "Atbash" comes from the first two letter pairs of the Hebrew alphabet. "At" represents Aleph (א) paired with Tav (ת) - the first and last letters. "Bash" represents Bet (ב) paired with Shin (ש) - the second and second-to-last letters. This naming convention elegantly describes the cipher's core mechanism: reversing the alphabet by pairing first-to-last, second-to-second-last, and so on throughout all 22 Hebrew letters. The name itself functions as a mnemonic device that Hebrew scribes used to remember the cipher's substitution pattern. According to The Jewish Chronicle, this naming system made the technique easy to reference and teach within scribal education without requiring lengthy explanations. The name immediately conveys the method to anyone familiar with the Hebrew alphabet's structure.

What is the Atbash code in the Bible?

The Atbash cipher appears three times in the biblical Book of Jeremiah. In Jeremiah 25

and 51, "Sheshach" (שֵׁשַׁךְ) encrypts "Babylon" (בָּבֶל). In Jeremiah 51, "Leb-kamai" (לֵב קָמַי) encrypts "Chaldea" or "Kasdim" (כַּשְׂדִּים). These encrypted names were used during the 6th century BCE when Babylon threatened Israel, possibly to protect the prophet from Babylonian authorities who might read the manuscripts or to add symbolic reversal to prophetic judgments about Babylon's eventual downfall. Biblical scholars continue to debate whether the encryption served practical security purposes or primarily rhetorical and symbolic functions. The Sefaria biblical database provides access to the original Hebrew texts where these cipher instances appear. See the Biblical Usage section for detailed analysis of each example, including letter-by-letter transformation demonstrations and scholarly interpretations of why Jeremiah employed this encryption technique.What does Sheshach mean in Jeremiah?

"Sheshach" (Hebrew: שֵׁשַׁךְ) is an Atbash-encrypted name for Babylon found in Jeremiah 25

and 51. When the Atbash cipher is applied by reversing the Hebrew alphabet, Sheshach transforms letter-by-letter into "Babel" or Babylon (בָּבֶל): Shin (ש) becomes Bet (ב), Shin (ש) becomes Bet (ב), and Final Kaf (ך) becomes Lamed (ל). The prophet Jeremiah used this encryption during Babylon's conquest of Judah in the 6th century BCE, possibly to avoid detection by Babylonian officials or to symbolize the reversal of Babylon's power that he prophesied would eventually occur. This represents the most famous example of Atbash cipher in historical texts and demonstrates one of the earliest documented uses of encryption in recorded history. The name "Sheshach" appears nowhere else in ancient texts as a geographical location, strongly supporting the scholarly consensus that it represents an Atbash cipher rather than an actual place name.How does the atbash cipher work?

The Atbash cipher works by reversing the alphabet: the first letter becomes the last, the second becomes second-to-last, and so on through all letters. In English, A becomes Z, B becomes Y, C becomes X, continuing through the entire 26-letter alphabet. For example, "HELLO" encrypts to "SVOOL" with each letter mapping to its reverse position: H→S, E→V, L→O, L→O, O→L. In the original Hebrew version with 22 letters, Aleph (א) pairs with Tav (ת), Bet (ב) with Shin (ש), continuing through the complete alphabet. The cipher is self-inverse, meaning applying it twice returns the original text - encryption and decryption use exactly the same process. No separate key is required since the transformation is fixed and based solely on the alphabet's structure. This simplicity made Atbash accessible to ancient Hebrew scribes who needed only alphabet knowledge to use it effectively. See the Technical Mechanism section for detailed worked examples in both Hebrew and English.

What is an example of atbash cipher?

A simple English example: The word "CODE" encrypts to "XLWV" (C→X, O→L, D→W, E→V). A sentence example: "HELLO WORLD" becomes "SVOOL DLIOW" with spaces preserved. The most famous historical example comes from Jeremiah 25

, where "Sheshach" (שֵׁשַׁךְ in Hebrew) encrypts "Babylon" (בָּבֶל). The Hebrew transformation works letter by letter: Shin (ש) transforms to Bet (ב), Shin (ש) to Bet (ב), and Final Kaf (ך) to Lamed (ל), spelling Babel or Babylon. This biblical example demonstrates how ancient Hebrew scribes used Atbash for politically sensitive content during the Babylonian conquest period. The encryption provided both practical discretion (making the text less immediately obvious to Babylonian officials) and symbolic meaning (reversing Babylon's name represented the prophesied reversal of its power). See the Biblical Usage and Worked Examples sections for more detailed demonstrations of Atbash transformation in both ancient Hebrew and modern English contexts.Is atbash cipher secure?

No, the Atbash cipher is not secure by modern standards. It has no secret key and only one possible transformation, making it extremely vulnerable to frequency analysis and pattern recognition attacks. A modern computer can break Atbash encryption instantly by simply applying the reversal transformation. Even manual cryptanalysis using basic frequency tables can decode Atbash messages in minutes. However, in 500 BCE when literacy was rare and the concept of systematic ciphers largely unknown to most people, it provided limited protection for sensitive texts against casual inspection. Ancient Hebrew scribes used it in contexts where even weak encryption offered value - deterring quick recognition by Babylonian officials unfamiliar with Hebrew scribal practices. Today, Atbash has purely educational value for teaching cryptography principles and demonstrating why monoalphabetic substitution is weak. Modern encryption methods like AES-256 or RSA are necessary for actual security needs. See the Security Analysis section for detailed discussion of Atbash's weaknesses and why it served ancient purposes despite offering no security against determined modern cryptanalysis.

Why did Hebrew scribes use atbash?

Hebrew scribes used Atbash for multiple possible reasons debated by scholars. First, political protection: encrypting sensitive names like Babylon during the Babylonian occupation may have protected the prophet Jeremiah and his scribes from persecution if manuscripts were discovered by hostile officials. Second, symbolic purposes: reversing Babylon's name may have symbolized the reversal of its power in prophetic judgment, adding rhetorical force to the message. Third, scribal tradition: Atbash may have been a conventional practice within Hebrew scribal communities for handling sensitive or sacred content, similar to euphemisms in modern writing. Fourth, mnemonic device: it may have served as a memory aid or organizational tool for scribes managing complex texts. The actual motivation likely combined practical and symbolic elements rather than serving any single purpose. The context of prophetic literature - where poetic devices, wordplay, and symbolic language were standard - suggests Atbash functioned on multiple levels simultaneously. See the Historical Origins and Biblical Usage sections for detailed analysis of the political, religious, and cultural contexts that informed Hebrew scribal encryption practices.

How did atbash evolve over time?

Atbash evolved from a practical cipher in biblical times (500 BCE) to a traditional scholarly tool across 2,500 years. After its biblical origins, it continued in rabbinic tradition - the Talmud (Shabbat 104a, circa 500 CE) discusses it as an exegetical and mnemonic device used for textual interpretation rather than encryption. Medieval Hebrew scholars (500-1500 CE) preserved the technique, with some evidence suggesting usage in Kabbalistic mystical texts where letter manipulation held symbolic spiritual meaning. During the Renaissance and early modern period (15th-17th centuries), it became part of cryptography history studies as European scholars investigated ancient secret writing methods. In modern times (1900s-present), Atbash serves primarily educational purposes: teaching cipher concepts in computer science courses, appearing in puzzles and recreational cryptography, and providing historical examples in cryptography education. It survived 2,500 years due to its simplicity, memorability, and most importantly, its connection to sacred biblical texts preserved through continuous Jewish religious and scholarly traditions. See the Evolution Through History section for complete details about Atbash's remarkable journey across civilizations and centuries.

What archaeological evidence exists for atbash?

The primary archaeological evidence for Atbash comes from ancient Hebrew manuscripts, particularly biblical texts containing the Book of Jeremiah dated to the 6th century BCE based on textual, linguistic, and historical analysis. The Dead Sea Scrolls (discovered 1947-1956, dated 3rd century BCE to 1st century CE) provide additional context for understanding Hebrew text manipulation practices during the Second Temple period. Scholar Hugh Schonfield documented potential Atbash usage in specific scroll passages, though scholars emphasize that case-by-case analysis with solid linguistic evidence is required for each claimed instance. No separate ancient "Atbash instruction manual" or dedicated cryptographic treatise has been discovered - our evidence comes from the cipher's actual usage in texts rather than explicit documentation of the technique itself. This is typical for ancient scribal practices, which were transmitted through apprenticeship and oral instruction rather than written manuals. The consistency of Atbash recognition across centuries of rabbinic commentary demonstrates continuous knowledge transmission even without archaeological cryptographic textbooks. See the Dead Sea Scrolls Connection section for detailed discussion of archaeological context and scholarly debates about Second Temple period encryption practices.

Who studies atbash cipher today?

Today, Atbash is studied by several distinct groups with different interests. First, biblical scholars and theologians analyze ancient Hebrew texts and prophetic literature, examining how encryption functions within religious contexts. Second, cryptography historians research the evolution of encryption methods from ancient times to modern computational systems, using Atbash as a foundational historical example. Third, computer science and cybersecurity educators teach foundational cipher concepts, demonstrating substitution principles and frequency analysis using Atbash's simplicity. Fourth, linguistics and Hebrew language scholars examine ancient text manipulation techniques as part of understanding how scribes worked with sacred languages. Fifth, archaeologists and Dead Sea Scrolls researchers investigate Second Temple period textual practices, considering how communities like Qumran handled sensitive documents. Universities with biblical studies, cryptography, or ancient Near Eastern studies programs often include Atbash in their curriculum. The cipher's unique position connecting religious history, linguistic analysis, and cryptographic evolution makes it relevant across multiple academic disciplines despite having no practical modern security applications.

How do you decode atbash cipher?

To decode Atbash, apply the same reversal process used for encoding since the cipher is self-inverse. For each letter in the encrypted text, substitute it with its pair from the reversed alphabet: Z→A, Y→B, X→C in English, or Tav→Aleph, Shin→Bet in Hebrew. For example, the ciphertext "SVOOL" decodes to "HELLO" by reversing each letter's position. Alternatively, use frequency analysis if you suspect a text is encrypted with Atbash but aren't certain: analyze letter frequency patterns in the ciphertext. The most common English letters (E, T, A) should appear as less common letters (V, G, Z) in Atbash ciphertext. Most online Atbash cipher tools automatically decode text by applying the reversal transformation. Since there's no variable key, decryption is trivial once you identify Atbash as the encryption method - unlike modern ciphers requiring key discovery, Atbash simply needs method recognition. The self-inverse property means no separate decryption algorithm exists; encryption and decryption are literally identical operations. See the Technical Mechanism section for step-by-step worked examples of both encryption and decryption processes.

Can atbash be used for English alphabet?

Yes, Atbash can easily be adapted for the English alphabet or any writing system with a fixed alphabetical sequence. The English version uses 26 letters instead of Hebrew's 22: A↔Z, B↔Y, C↔X, D↔W, E↔V, F↔U, G↔T, H↔S, I↔R, J↔Q, K↔P, L↔O, M↔N, and the pattern continues as a mirror image through the entire alphabet. The same reversal principle applies - pair first-to-last, second-to-second-last, continuing through the complete alphabet. While the original Atbash was designed specifically for Hebrew's 22-letter consonantal alphabet structure, the mathematical principle of alphabet reversal works universally for any writing system with a fixed, ordered alphabet. Modern recreational cryptography, puzzle games, and educational cryptography courses frequently use English Atbash because it's easier for English-speaking students to understand than working with Hebrew letters. The adaptation demonstrates that Atbash represents a general cryptographic principle rather than being limited to its original Hebrew application. Any alphabet can be "folded in half" to create reverse mappings following the same substitution logic that ancient Hebrew scribes employed 2,500 years ago.

What is atbash's place in cryptography history?

Atbash holds a foundational place in cryptography history as one of the oldest documented ciphers, dating to approximately 500-600 BCE and predating the Roman Caesar cipher by about 500 years. It represents humanity's earliest confirmed systematic attempt to conceal information through alphabet transformation. As a monoalphabetic substitution cipher, Atbash belongs to the first generation of cipher techniques, which later evolved into more sophisticated polyalphabetic systems like the Vigenère cipher (16th century) that used multiple substitution alphabets. The Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security (Springer) classifies Atbash alongside Caesar cipher as foundational examples in classical cryptography. Today, cryptography educators worldwide use Atbash to teach fundamental concepts: substitution principles, the importance of key space, frequency analysis vulnerabilities, and the evolution from ancient to modern encryption. It serves as a historical benchmark showing 2,500 years of cryptographic development - from simple letter reversal used by ancient Hebrew scribes to complex computational algorithms like AES and RSA that secure modern internet communications. See the Conclusion section for complete discussion of Atbash's enduring legacy and significance in the broader history of human information security efforts.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Atbash Cipher

The history of the Atbash cipher represents far more than the story of a simple encryption technique. It illuminates humanity's earliest systematic attempts to protect sensitive information, demonstrates how cultural and religious traditions preserve knowledge across millennia, and provides a window into the sophisticated intellectual world of ancient Hebrew scribal communities.

From its documented origins in the 6th century BCE Book of Jeremiah through 2,500 years of continuous transmission in rabbinic scholarship, medieval Hebrew studies, and modern cryptography education, Atbash has maintained remarkable staying power. This longevity stems from multiple factors: embedding in sacred biblical texts ensured religious communities preserved the knowledge, its mathematical simplicity made it easy to teach and remember, and its position as humanity's oldest documented cipher gives it enduring historical significance.

The three instances of Atbash in Jeremiah - encrypting "Babylon" as "Sheshach" twice and "Chaldea" as "Leb-kamai" once - remain the most thoroughly documented and historically significant examples of ancient encryption in existence. These biblical examples provided archaeological and textual evidence that allowed scholars to trace cryptographic thinking back to ancient Israel, establishing a documented history of systematic encryption five centuries before the Roman Caesar cipher.

The Dead Sea Scrolls connection, while requiring careful scholarly analysis, demonstrates that encryption techniques continued in Hebrew textual traditions during the Second Temple period. Hugh Schonfield's controversial research on potential Atbash usage in Qumran documents illustrates ongoing academic interest in understanding how ancient communities protected and symbolically encoded their most sensitive texts.

Atbash's evolution from practical cipher to traditional scholarly tool to modern educational example shows how intellectual techniques can transcend their original purposes. What began as a method for Hebrew prophets to handle politically dangerous content became a rabbinic interpretive tool, a medieval Kabbalistic symbolic system, and ultimately a foundational example in university cryptography courses worldwide.

Why Atbash Matters Today

Modern society, surrounded by sophisticated encryption protecting everything from bank transactions to private communications, might dismiss Atbash as a historical curiosity. Yet this ancient cipher remains significant for several reasons:

Historical Understanding: Atbash represents the earliest documented systematic encryption, providing evidence of human information security concerns dating back 2,500 years. Understanding this history contextualizes modern cryptographic challenges as part of humanity's long-standing need to protect sensitive information.

Educational Foundation: The cipher's simplicity makes it perfect for teaching fundamental cryptography concepts. Students can understand Atbash's mechanism in minutes, then immediately grasp why it fails - learning about substitution principles, frequency analysis, and the critical importance of key space in modern security.

Cultural Heritage: Atbash connects to biblical scholarship, Jewish tradition, and ancient Near Eastern history. Its preservation through religious and scholarly communities demonstrates how cultural institutions maintain knowledge across generations and civilizations.

Cryptographic Evolution Perspective: Studying Atbash provides a starting point for understanding how encryption evolved from simple letter reversal to complex computational algorithms. The journey from Atbash to AES spans 2,500 years of human intellectual development, showing progress from scribal techniques to mathematical theory to computational security.

Key Takeaways

Atbash is the oldest documented cipher system, with confirmed usage dating to approximately 500-600 BCE in the biblical Book of Jeremiah.

Three biblical instances encrypt politically sensitive names: "Sheshach" for Babylon (twice) and "Leb-kamai" for Chaldea, providing concrete historical evidence.

Simple alphabet reversal mechanism requires no separate key. First letter pairs with last, second with second-to-last, continuing through the complete alphabet.

Self-inverse property means encryption and decryption use identical processes. Applying Atbash twice returns the original text.

Not secure by modern standards, being vulnerable to frequency analysis and having zero key space, but served limited purposes in ancient contexts.

Survived 2,500 years through continuous preservation in Jewish religious and scholarly traditions, from biblical texts through rabbinic literature to modern education.

Educational value as a foundational example teaching substitution ciphers, demonstrating security weaknesses, and illustrating cryptographic evolution.

Cultural and historical significance connecting biblical scholarship, ancient Near Eastern history, and the development of human information security practices.

Further Resources

Scholarly Sources:

For deeper academic exploration of Atbash and classical cryptography.

- Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security (Springer) - Comprehensive academic reference classifying Atbash within cryptographic history

- Sefaria Biblical Database - Primary source access to original Hebrew texts: Jeremiah 25, 51, 51, and Talmud Shabbat 104a

- Oxford University Humanities Faculty - Educational resources on ancient ciphers including Atbash

- The Jewish Chronicle - Cultural and linguistic context for Atbash's Hebrew origins

- Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) - Historical scholarly perspective on Atbash in Jewish tradition