1. Introduction: What is a Keyword Cipher?

In 1587, a seemingly secure cipher led to the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. For over two centuries, Louis XIV's "Great Cipher" protected France's deepest state secrets, remaining unbroken until 1890. These historical ciphers, which shaped diplomatic intrigue and military strategy across Renaissance Europe, all shared a common foundation: the keyword cipher.

A keyword cipher is a monoalphabetic substitution cipher that uses a keyword to generate a mixed cipher alphabet. Unlike the simple Caesar cipher, which shifts the entire alphabet by a fixed number of positions, the keyword cipher creates a more complex substitution pattern by placing a keyword (with duplicate letters removed) at the beginning of the cipher alphabet, followed by the remaining unused letters in alphabetical order. This generates a unique substitution table where each plaintext letter always maps to the same ciphertext letter.

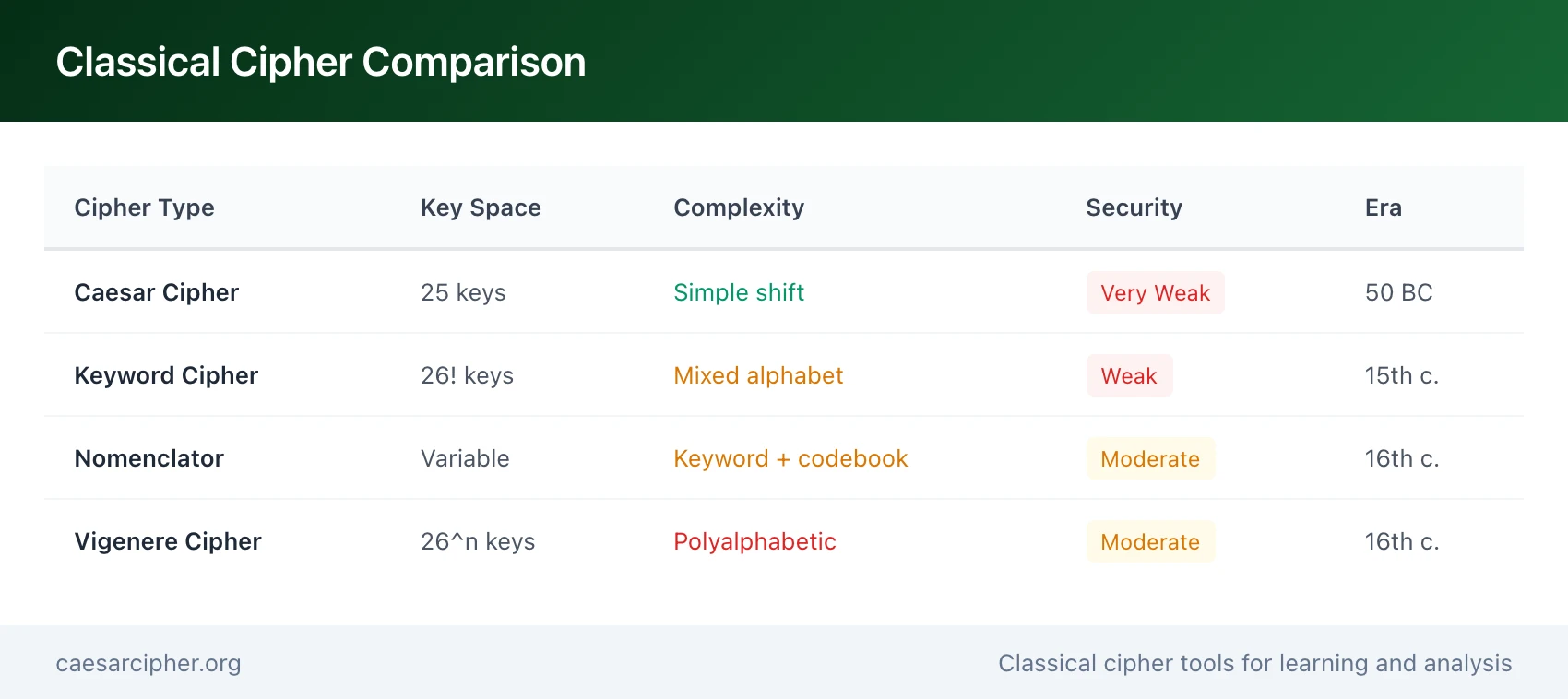

The keyword cipher occupies a crucial position in the evolution of classical cryptography. It represents the bridge between simple shift ciphers like the Caesar cipher and more sophisticated systems like nomenclators and polyalphabetic ciphers. Emerging during the Renaissance period in 15th-century Europe, keyword ciphers served as the backbone of diplomatic and military communications for nearly four centuries, from approximately 1400 to 1800 CE.

In this comprehensive guide, you'll discover the complete history of keyword ciphers: their Renaissance origins, their role in shaping European diplomacy and warfare, famous historical examples including Louis XIV's Great Cipher and the American Civil War cipher disks, how cryptanalysts broke these codes using frequency analysis, and why they eventually became obsolete. You'll also learn the practical mechanics of creating and breaking keyword ciphers, and understand their modern educational applications in teaching cryptography fundamentals.

2. How Keyword Cipher Works: Complete Tutorial

2.1 The Basic Algorithm

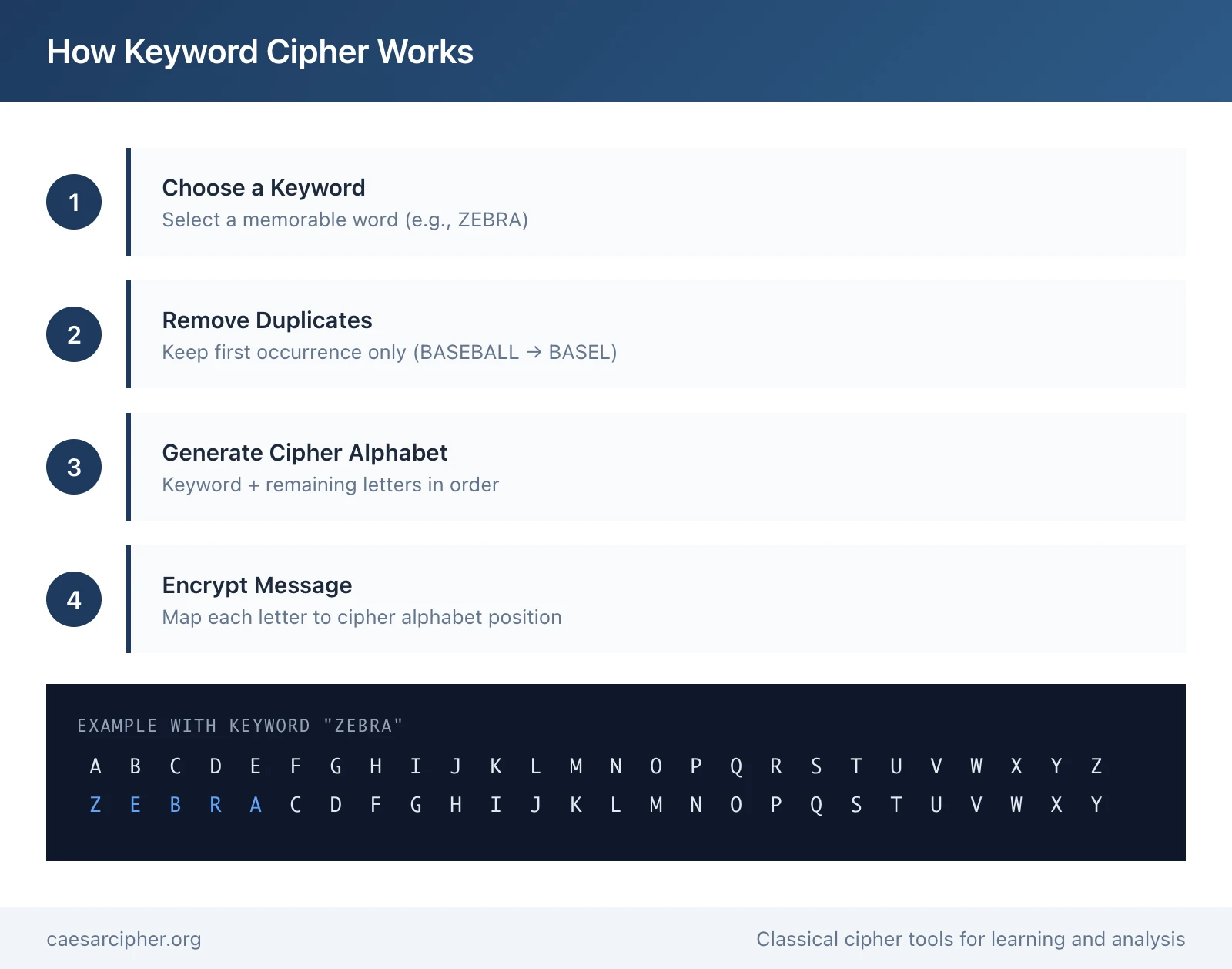

To create a keyword cipher, follow these five fundamental steps:

Step 1: Choose a keyword Select a memorable word or phrase as your secret key. Ideal keywords have distinct letters without repetition, though any word will work. Common examples include ZEBRA, CIPHER, WIZARD, or KRYPTOS (famously used in the CIA's Kryptos sculpture).

Step 2: Remove duplicate letters If your keyword contains repeated letters, keep only the first occurrence of each. For example:

- BASEBALL → BASEL (removes duplicate B, A, L)

- MISSISSIPPI → MISP (keeps only first M, I, S, P)

- GRANDMOTHER → GRANDMOTHE (removes duplicate R and E)

Step 3: Generate the cipher alphabet Place your processed keyword at the start of the alphabet, then append all remaining unused letters in their normal alphabetical order. For example, using keyword ZEBRA:

Normal alphabet: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Cipher alphabet: Z E B R A C D F G H I J K L M N O P Q S T U V W X Y

Step 4: Encrypt your message Map each plaintext letter to its corresponding position in the cipher alphabet. Using the ZEBRA example:

- Plaintext: HELLO WORLD

- H (position 8) → G

- E (position 5) → J

- L (position 12) → K

- L (position 12) → K

- O (position 15) → L

- Ciphertext: GJKKL VLOKA

Step 5: Decrypt messages To decrypt, reverse the process by mapping cipher letters back to their normal alphabet positions using the same keyword-generated alphabet.

2.2 Worked Examples

Example 1: ZEBRA Keyword (Basic)

Keyword: ZEBRA (no duplicates to remove)

Cipher alphabet generation:

Normal: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Cipher: Z E B R A C D F G H I J K L M N O P Q S T U V W X Y

Encryption:

- Plaintext: FLEE AT ONCE

- Process: F→C, L→K, E→J, E→J, (space), A→Z, T→S, (space), O→L, N→M, C→B, E→J

- Ciphertext: CJJJ ZS LMBJ

Example 2: GRANDMOTHER Keyword (Duplicate Removal)

Keyword: GRANDMOTHER Processed: GRANDMOTHE (removes second R and second E)

Cipher alphabet:

Normal: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Cipher: G R A N D M O T H E B C F I J K L P Q S U V W X Y Z

Encryption:

- Plaintext: FLEE AT ONCE WE ARE DISCOVERED

- Ciphertext: BCDD GS JIAD WD GPD NHQAJUDPDN

This example demonstrates how duplicate removal affects the cipher alphabet construction.

Example 3: KRYPTOS Keyword (CIA Connection)

Keyword: KRYPTOS (from the famous CIA sculpture) Processed: KRYPTOS (no duplicates)

Historical context: The Kryptos sculpture at CIA headquarters uses this keyword in one of its encrypted messages, making it one of the most famous modern examples of keyword cipher usage.

Cipher alphabet:

Normal: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Cipher: K R Y P T O S A B C D E F G H I J L M N Q U V W X Z

2.3 Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Not removing duplicate letters: Forgetting to filter repeated letters in the keyword creates an invalid cipher alphabet

- Incomplete alphabet: Failing to append all remaining letters after the keyword results in untranslatable characters

- Case handling inconsistency: Mixing uppercase and lowercase without a consistent rule causes encryption/decryption errors

- Security misconception: Believing that a longer keyword makes the cipher more secure (it remains vulnerable to frequency analysis regardless)

- Special character confusion: Attempting to encrypt non-alphabetic characters without defining how to handle them

3. Historical Origins and Evolution (15th-19th Century)

3.1 Renaissance Emergence (15th-16th Century)

The keyword cipher emerged from a rich history of earlier cryptographic developments. Ancient civilizations had experimented with various forms of secret writing: the Spartans used the scytale (circa 400 BC), a transposition device involving wrapped leather strips; the Greeks developed the Polybius Square (2nd century BC) for coordinate-based substitution; and the Romans employed the Caesar cipher (circa 50 BC), a simple shift substitution system.

The critical breakthrough in cryptanalysis came in 850 AD when the Arab scholar Al-Kindi first systematically described frequency analysis in his manuscript "A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages." This work laid the foundation for breaking all monoalphabetic substitution ciphers and would prove crucial to understanding the vulnerability of keyword ciphers centuries later.

In the intricate political landscape of Renaissance Italy during the 15th century, where rival city-states like Venice, Florence, Milan, and Naples competed for power and influence, simple shift ciphers proved inadequate for diplomatic security. The complex web of alliances, betrayals, and espionage that characterized this period demanded more sophisticated encryption methods. Keyword-based letter rearrangement ciphers emerged from this need, offering far greater complexity than simple Caesar shifts while remaining practical for manual encryption and decryption.

Leon Battista Alberti's invention of the cipher disk in 1466 marked another milestone, introducing the concept of polyalphabetic ciphers. While not itself a keyword cipher, Alberti's work influenced cryptographic thinking and showed the direction that encryption would eventually take beyond simple monoalphabetic substitution.

3.2 The Nomenclator Era (1500-1800)

A nomenclator cipher is a hybrid encryption system that combines keyword-based monoalphabetic substitution with a codebook for common words, names, and phrases. Emerging in the 15th century and becoming the standard diplomatic cipher through the 18th century, nomenclators represented the peak of classical cipher complexity. The term derives from "nomenclator"—an official who announces visitors' titles at formal events—reflecting its initial focus on encoding important names and titles. Eventually expanding to include thousands of code symbols, nomenclators attempted to compensate for the fundamental frequency analysis vulnerability of monoalphabetic substitution.

Evolution of Nomenclator Complexity

| Period | Symbol Count | Components | Typical Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early (15th-16th c.) | Hundreds | Keyword alphabet + limited codebook | Diplomatic correspondence, royal courts |

| Middle (16th-17th c.) | Thousands | Keyword substitution + extensive codebook + homophones | All major European powers, espionage |

| Peak (18th c.) | Up to 50,000 | Massive codebooks attempting to compensate for frequency weakness | Diplomatic services, intelligence agencies |

| Decline (19th c.) | Varied | Being replaced by polyalphabetic and mechanical ciphers | Transitioning to modern methods |

This nomenclator system became the standard diplomatic encryption method from the 16th through 18th centuries. All major European powers—England, France, Spain, Venice, Austria—employed nomenclators for their sensitive communications. Ambassadors carried pre-agreed codebooks and keywords, with regular updates and key changes to maintain security. However, the underlying monoalphabetic substitution weakness remained.

3.3 Famous Historical Examples

3.3.1 Louis XIV's Great Cipher (Grand Chiffre)

For over two centuries, one cipher protected France's deepest secrets. Created by the Rossignol family—Antoine and his son Bonaventure, who served as royal cryptographers for multiple French monarchs—during Louis XIV's reign in the 17th century, the Great Cipher (Grand Chiffre) represented the peak of nomenclator complexity.

Structure and Complexity: The Great Cipher employed 587 different numerical symbols, each representing French syllables rather than individual letters. For example, the number 124 might represent the syllable "les," while 22 could represent "en," and 125 "ne." Some symbols represented complete names or places, while others stood for common words. The system also included "nulls" (meaningless symbols designed to confuse cryptanalysts) and sophisticated "traps," such as symbols meaning "ignore the previous code group."

Historical Significance: The cipher protected French state secrets for over 200 years and was considered utterly unbreakable during its active use. Louis XIV's government employed it for the most sensitive diplomatic correspondence, military planning, and court intrigues. The Rossignol family operated the Cabinet Noir (Black Chamber), France's cipher bureau, from either their estate at Juvisy or the king's private study at Versailles.

The Breaking (1890-1893): The dramatic breakthrough came in 1890 when French military cryptanalyst Étienne Bazeries undertook the challenge of decrypting old messages encrypted with the Great Cipher. Working without any key or basic understanding of the system's structure, Bazeries spent three years analyzing the patterns. His crucial insight came when he realized the numbers represented French syllables rather than single letters. By guessing that the sequence 124-22-125-46-345 likely meant "les ennemis" (the enemies), he unlocked the entire cipher system.

Revelations: When Bazeries finally cracked the Great Cipher, the decrypted messages revealed historical secrets that had been hidden for over two centuries. Most famously, they provided clues about the "Man in the Iron Mask" mystery, revealing that General Vivien de Bulonde had been imprisoned after a military failure. The Great Cipher demonstrated that even extremely complex nomenclators remained fundamentally vulnerable to determined cryptanalysis, though the labor required was immense.

3.3.2 American Civil War Field Ciphers (1861-1865)

During the American Civil War, both Union and Confederate forces employed keyword-based cipher disks for field communications, representing a mechanical implementation of the keyword cipher principle.

Confederate Cipher Disk: The Confederate cipher disk, crafted from brass, consisted of two concentric rings each bearing the alphabet. Only five authentic examples survive today: two in private collections, one at the Smithsonian Institution, and two at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia. Created by Francis LaBarre, these disks could function as simple substitution ciphers when aligned at a fixed position, or as more complex Vigenère-style ciphers when the keyword determined different alphabet alignments for each letter.

Keywords Used: Confederate cipher operators employed keywords such as "Manchester Bluff," "Complete Victory," and "Come Retribution" (used near war's end). However, a critical security flaw emerged: too few keywords were used, and they were reused frequently. Additionally, only the most important words in messages were encrypted, leaving contextual clues for Union cryptanalysts.

Union Cipher Systems:

- General George McClellan (1861): Employed word transposition ciphers

- Anson Stager: Western Union's first superintendent created a transposition cipher adopted army-wide in 1862

- Major Albert J. Myer: Developed and patented an improved cipher disk that combined letters with numbers for additional obfuscation, designed to work with the wig-wag flag signaling system

Why Confederate Systems Were Broken: Although the Vigenère principle should have provided good security, Union cipher analysts routinely broke Confederate messages. The problem wasn't the system itself but its implementation: keywords were too few, reused repeatedly, and only portions of messages were encrypted (a practice called the "Vicksburg System"). This allowed Union cryptanalysts to identify patterns and reconstruct the keys.

3.3.3 Mary, Queen of Scots (1587)

In 1586, Mary Queen of Scots, imprisoned for 19 years, became entangled in the Babington Plot—a conspiracy to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I and place Mary on the English throne. Mary used a sophisticated nomenclator cipher for her secret correspondence with the conspirators.

The Cipher System: Mary's cipher represented one of the earliest codebooks in cryptographic history. It included:

- 23 symbols representing letters (excluding j, v, w)

- 35 symbols representing complete words or phrases

- Introduction of homophonic substitution (multiple symbols for high-frequency letters)

- Null entries (interference symbols)

- Regularly changed alphabet tables to maintain dynamic security

The Cryptanalysis: Thomas Phelippes, the cipher analyst employed by Francis Walsingham (Elizabeth I's spymaster), successfully broke Mary's cipher using frequency analysis—the same technique first described by Al-Kindi in the 9th century. Phelippes methodically:

- Established character frequency distributions

- Proposed values for the most common characters

- Gradually identified and ignored null symbols

- Guessed code words from context

- Built up a complete understanding of the cipher system

The Critical Evidence: On July 7, 1586, Phelippes decrypted the only letter from Babington outlining the plot. Mary's encrypted reply on July 17, 1586, contained explicit orders to assassinate Elizabeth. Gilbert Gifford, a double agent, provided copies of messages to Walsingham before delivering them to their intended recipients. Phelippes even forged an addition to Mary's letter, requesting that the conspirators list all names of participants.

Historical Lesson: Mary and Babington's over-confidence in their substitution cipher led them to discuss assassination plans explicitly—something they might have been more cautious about if communicating in plaintext. Their trust in the cipher made them vulnerable to Phelippes's forgery. As cryptographic historians note: "The correct use of a strong cipher is a clear boon to sender and receiver, but the misuse of a weak cipher can generate a very false sense of security." Mary was tried in October 1586 and beheaded for her participation in the assassination conspiracy, making this one of history's most famous examples of cryptanalysis changing the course of events.

3.4 Diplomatic and Military Usage

European Diplomatic Correspondence (16th-18th Century)

Throughout the 16th to 18th centuries, keyword-based nomenclators served as the standard practice for diplomatic communication among all major European powers. English, French, Spanish, Venetian, and Austrian diplomatic services all maintained sophisticated cipher systems:

- Venice: Developed some of the most advanced nomenclators, with the Venetian Council of Ten employing dedicated cipher secretaries

- France: Maintained extensive diplomatic cipher services, eventually creating the Cabinet Noir

- England: Operated the Secret Office for intercepting and decrypting foreign correspondence

- Spain: Developed complex cipher systems for communication with its vast colonial empire

Ambassadors carried pre-agreed codebooks and keywords, with security protocols requiring:

- Regular key updates (monthly or quarterly)

- Secure courier systems for encrypted diplomatic pouches

- Redundant encryption for the most sensitive passages

- Weeks or even months of delivery time for international correspondence

Black Chambers and the Cryptographic Arms Race

The systematic interception and decryption of diplomatic correspondence led to the establishment of government cryptanalysis offices across Europe:

Major Black Chambers:

- Cabinet Noir (France): Louis XIV's secret cipher bureau, operated by the Rossignol family

- Geheime Kabinets-Kanzlei (Austria): The Secret Cabinet Chancellery, one of the most effective cryptanalysis operations

- English Secret Office: Intercepted and analyzed foreign diplomatic mail passing through British territories

- Venetian Cipher Bureau: The Republic of Venice maintained sophisticated cryptanalysis capabilities

As historical records reveal, "Nations established 'Black Chambers' to intercept and decrypt foreign diplomatic codes, sparking a 'cryptographic arms race.'" This systematic competition drove continuous improvements in both cipher design and cryptanalysis techniques, with each advance in encryption methods met by corresponding advances in code-breaking capabilities.

The professionalization of cryptanalysis during this period laid the groundwork for modern intelligence agencies and demonstrated that no monoalphabetic cipher, regardless of complexity, could withstand determined and systematic analysis.

3.5 Decline and Polyalphabetic Transition (19th Century)

By the 19th century, several factors combined to render keyword ciphers obsolete for serious cryptographic applications:

Factor 1: Frequency Analysis Maturity By the mid-19th century, frequency analysis methods were well-understood across Europe. What had once been a closely guarded secret known only to skilled cryptanalysts became part of standard military training. Government cipher bureaus could routinely break even complex nomenclators, making monoalphabetic substitution fundamentally insecure.

Factor 2: The Kasiski Method (1863) Friedrich Kasiski published his method for breaking Vigenère ciphers in 1863, proving that even polyalphabetic ciphers could be systematically analyzed. While this made polyalphabetic ciphers less secure than previously believed, they still remained significantly harder to break than any monoalphabetic system including keyword ciphers.

Factor 3: Technological Change The telegraph era brought new communication needs and possibilities. Commercial codebooks became widely available for business telegraphy, while mechanical cipher machines began to emerge. The transition from handwritten diplomatic dispatches to telegraphic communication demanded encryption methods suitable for rapid, remote transmission.

Factor 4: Theoretical Understanding Cryptanalysis evolved from an art into a science during the 19th century. Statistical methods became more sophisticated, and the theoretical weakness of monoalphabetic substitution was fully understood. This recognition drove military and diplomatic services to seek stronger encryption systems.

Conclusion: By the late 19th century, keyword ciphers had become obsolete for protecting sensitive communications. They were replaced by polyalphabetic systems (like Vigenère variants), mechanical cipher machines, and eventually the electrical rotor machines of the World War I and II era, including the famous Enigma machine. However, their historical importance as a crucial evolutionary step in cryptography cannot be overstated—they bridge the gap between ancient simple ciphers and modern encryption science.

4. Cryptanalysis and Security Analysis

4.1 Vulnerability to Frequency Analysis

The fundamental weakness of keyword ciphers lies in their monoalphabetic nature: the same plaintext letter always maps to the same ciphertext letter throughout the entire message. No matter how complex the keyword or how large the theoretical key space, this one-to-one correspondence preserves the statistical frequency distribution of the plaintext language.

English Letter Frequency Distribution:

E: 12.7% T: 9.1% A: 8.2% O: 7.5% I: 7.0%

N: 6.7% S: 6.3% H: 6.1% R: 6.0% D: 4.3%

L: 4.0% C: 2.8% U: 2.8% M: 2.4% W: 2.4%

F: 2.2% G: 2.0% Y: 2.0% P: 1.9% B: 1.5%

V: 1.0% K: 0.8% J: 0.2% X: 0.2% Q: 0.1%

Z: 0.1%

These frequency patterns persist in ciphertext regardless of the keyword used. The most frequent ciphertext letter almost always corresponds to E in English text, the second most frequent to T or A, and so on. These patterns are like fingerprints—they remain visible no matter how the alphabet is scrambled.

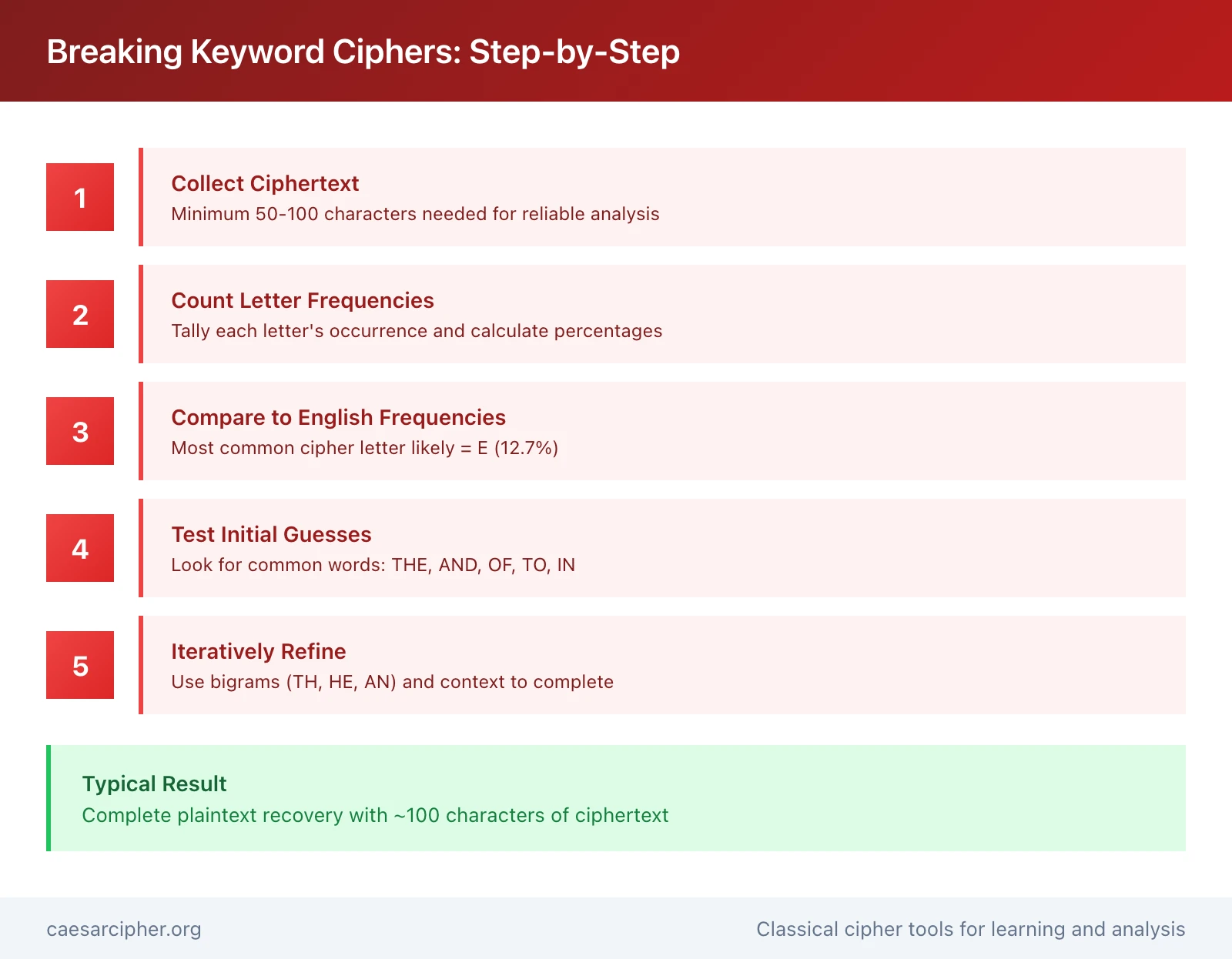

Unicity Distance: According to information theory, "the unicity distance of English, 27.6 letters of ciphertext are required to crack a mixed alphabet simple substitution." In practice, typically about 50-100 letters are needed for reliable frequency analysis. With modern computational methods, even shorter ciphertexts can be broken through automated searching algorithms.

4.2 Step-by-Step Breaking Tutorial

Method 1: Frequency Analysis (The Classical Approach)

Step 1: Collect sufficient ciphertext

- Minimum requirement: 50-100 characters

- More text provides better statistical accuracy

- Remove spaces and punctuation for frequency counting

Step 2: Count letter frequencies

- Tally each letter's occurrence

- Calculate percentages

- Sort by frequency (highest to lowest)

- Create a frequency table for visualization

Step 3: Compare to English frequencies

- Most common ciphertext letter → likely E (12.7%)

- Second most common → likely T (9.1%) or A (8.2%)

- Third most common → likely O (7.5%), I (7.0%), or N (6.7%)

- Map probable substitutions based on frequency matching

Step 4: Test initial guesses

- Apply substitutions to the ciphertext

- Look for common words: THE, AND, OF, TO, IN, IS, IT

- Check if partial plaintext makes linguistic sense

- Adjust mappings based on context and word patterns

Step 5: Iteratively refine

- Fix obviously correct mappings

- Use word patterns to guess remaining letters

- Look for doubled letters (LL, SS, EE, OO)

- Identify common letter combinations (TH, ER, ON, AN, RE, IN)

- Continue until complete plaintext emerges

- Validate the final result for coherence

Method 2: Known-Plaintext Attack

When any portion of the plaintext is known (even a single word), cryptanalysis becomes dramatically easier:

Process:

- Identify known plaintext-ciphertext pairs

- Create direct substitution mappings from these pairs

- Apply mappings to decrypt the rest of the message

- Fill in remaining letters using context or frequency analysis

Example:

- Known: "ATTACK" encrypts to "ZQQZBA"

- Derive: A→Z, T→Q, C→B, K→A

- Apply these four mappings to the rest of the ciphertext

- Very fast and effective approach

Historical Context: Many historical ciphers were broken this way. Diplomatic correspondence often contained predictable elements:

- Standard salutations: "Your Majesty," "Your Excellency"

- Common phrases: "Respectfully," "I have the honor to inform you"

- Known names of recipients and senders

- Date and location references

Even partial plaintext knowledge provides an enormous advantage, allowing cryptanalysts to bootstrap their way to the complete alphabet mapping quickly.

Method 3: Keyword Extraction from Cipher Alphabet

If you have access to the cipher alphabet (perhaps reconstructed through frequency analysis), you can sometimes identify the original keyword by recognizing patterns:

Pattern Recognition: Look for consecutive letters at the end of the cipher alphabet. These indicate where the keyword ends and the remaining alphabet begins.

Example:

Cipher alphabet: ZEBRACKDFGHIJLMNOPQSTUVWXY

Notice: ...STUVWXY are consecutive at the end

This pattern suggests the keyword ends before S

Therefore, the keyword likely is: ZEBRA

Why This Works:

- Keyword letters appear mixed at the start of the cipher alphabet

- Remaining letters are appended in normal alphabetical order

- Consecutive sequences reveal where the keyword portion ends

- This narrows the keyword search space significantly

Limitations:

- Not always produces a clear pattern

- Keywords ending with letters near Z may not show obvious sequences

- Useful as a hint rather than a guaranteed method

- Works best when the keyword is relatively short

4.3 Advanced Cryptanalysis Methods

Bigram Analysis

Analyzing two-letter combinations provides faster convergence than single-letter frequency analysis:

Most Common English Bigrams:

- TH: 3.16%

- HE: 2.33%

- AN: 1.73%

- IN: 1.64%

- ER: 1.54%

Method:

- Count all two-letter sequences in the ciphertext

- Map the most common to TH, HE, AN, IN

- Use these mappings as strong indicators

- Cross-reference with single-letter frequency

If the bigram "XY" appears very frequently in ciphertext, it likely represents "TH" in plaintext.

Trigram Analysis

Three-letter combinations provide even stronger discriminators:

Most Common English Trigrams:

- THE: 1.81%

- AND: 0.73%

- ING: 0.72%

- HER: 0.36%

- HAT: 0.31%

Power of Trigram Analysis: Identifying "THE" in ciphertext often provides three letter mappings immediately and can break the entire cipher. The limited number of possible three-letter sequences makes trigram analysis particularly effective.

Strategy: "If you can identify THE in ciphertext, you've discovered three letter mappings and possibly broken the cipher."

Hillclimbing Algorithm (Computer-Automated Breaking)

Modern computers can break keyword ciphers in seconds using optimization algorithms:

Process:

- Start with a random substitution key

- Calculate a fitness score (how English-like the decrypted result is)

- Make small random changes to the key

- Keep changes that improve the fitness score

- Repeat until convergence to a maximum

Performance:

- Breaks keyword ciphers in seconds on modern hardware

- Requires no manual analysis

- Doesn't need to know or guess the keyword

- Demonstrates the practical insecurity of classical ciphers

Fitness Functions: Common methods include:

- Bigram frequency matching

- Trigram frequency matching

- Dictionary word recognition

- N-gram log-likelihood scores

Modern Significance: "What took human cryptanalysts hours with pencil and paper, a computer can achieve in seconds." This demonstrates why no classical cipher provides real security in the modern era.

4.4 Worked Breaking Example

Let's walk through a complete cryptanalysis demonstration:

Challenge Ciphertext:

QIJ PJZVLA BJVIJA VQ QIJ MJGVQQVQD TY QIJ YVYQJJQQI

BJJQZMA VQ VJQQJQQA

(66 characters—sufficient for frequency analysis)

Step 1: Frequency Analysis

Count each letter:

J: 13 (19.7%) ← Most frequent

Q: 9 (13.6%) ← Second most

V: 8 (12.1%) ← Third most

I: 6 (9.1%)

Y: 5 (7.6%)

M: 4 (6.1%)

T: 4 (6.1%)

A: 3 (4.5%)

G: 2 (3.0%)

Z: 2 (3.0%)

L: 2 (3.0%)

P: 1 (1.5%)

Initial Hypotheses:

- J (19.7%) probably = E (most common letter in English)

- Q (13.6%) probably = T (second most common)

- V (12.1%) probably = A or O

Step 2: Apply Initial Guesses

Replace J→E and Q→T:

THE P_E_L_ BE_E_E _T THE BE____N_ __ THE ______ETH

BE_T___ _N __ENTENN_

Excellent! The pattern "THE" appears twice, confirming our guesses were correct.

Step 3: Word Pattern Recognition

Looking at the partial decryption:

- "T THE BE____N" likely reads "AT THE BEGINNING"

- "P_E_L_" with the pattern suggests "PEOPLE"

- First word is clearly "THE"

From "AT THE BEGINNING":

- V = A (confirmed)

- M = G

- G = I

- I = N

Step 4: Continue Progressive Substitution

Applying additional mappings:

THE PEOPLE BELIE_E AT THE BEGINNING O_ THE _I_TEENTH

BENTU__ IN _IGENERE

From context:

- Y = F

- Z = V

- L = C

- T = O

- A = R

Step 5: Complete Decryption

Final plaintext revealed:

THE PEOPLE BELIEVE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE FIFTEENTH

CENTURY IN VIGENERE

Step 6: Identify the Keyword

Reconstructing the cipher alphabet from our discovered mappings:

Normal alphabet: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Cipher alphabet: C I P H E R A B D F G J K L M N O Q S T U V W X Y Z

Keyword identified: CIPHER

Time Required:

- Manual analysis: 15-30 minutes for an experienced cryptanalyst

- Computer hillclimbing: Less than 10 seconds

- Automated tools: Nearly instantaneous

This example demonstrates that with sufficient ciphertext (50+ characters), keyword ciphers offer no practical security against even manual cryptanalysis.

4.5 Security Implications

Why Keyword Cipher is NOT Secure for Modern Use:

Despite a theoretical key space of 26! (approximately 4 × 10²⁶, or 88 bits), the keyword cipher offers zero practical security against modern cryptanalysis:

Security Weaknesses:

- Trivially Breakable: 50-100 characters sufficient for manual breaking

- Computer Breaking: Automated tools crack it in seconds

- No Forward Secrecy: Reusing the same key is catastrophic

- Frequency Patterns: Fundamental monoalphabetic weakness cannot be mitigated

Security Comparison:

| Cipher Type | Theoretical Security | Practical Security | Breaking Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keyword cipher | 88 bits (26!) | ~0 bits | Frequency analysis (manual) |

| AES-128 | 128 bits | 128 bits | No known practical attack |

| RSA-2048 | 2048 bits | ~112 bits | No known practical attack |

Educational Value: The keyword cipher's value today lies entirely in education, not security:

- Teaching substitution cipher fundamentals

- Demonstrating cryptanalysis techniques

- Illustrating why monoalphabetic systems fail

- Understanding cryptographic evolution from classical to modern

Critical Serving: The keyword cipher serves as a critical stepping stone in understanding cryptographic evolution from classical to modern systems, but it should never be used to protect real information in any contemporary context.

5. Comparison with Other Classical Ciphers

5.1 Keyword Cipher vs Caesar Cipher

While both keyword cipher and Caesar cipher are monoalphabetic substitution ciphers, they differ significantly in complexity, key space, and historical usage.

Similarities:

- Both use monoalphabetic substitution (single fixed alphabet)

- Both rearrange the alphabet according to a key

- Both preserve letter frequency patterns

- Both vulnerable to frequency analysis

- Both historically significant but obsolete for real security

Detailed Comparison Table:

| Feature | Caesar Cipher | Keyword Cipher |

|---|---|---|

| Key Type | Numeric shift (0-25) | Word/phrase |

| Key Space | 25 (very small) | 26! ≈ 2⁸⁸ (theoretical) |

| Alphabet Pattern | Simple ROT-n shift | Mixed based on keyword |

| Key Memorability | Easy (remember number) | Medium (remember word) |

| Security Level | Very Low | Low |

| Breaking Method | Brute force (25 tries) | Frequency analysis (50+ chars needed) |

| Breaking Difficulty | Trivial (minutes by hand) | Easy (30 min - 1 hour by hand) |

| Historical Period | Ancient Rome (~50 BC) | Renaissance (15th-19th c.) |

| Complexity | Simplest substitution possible | More sophisticated |

| Modern Use | Educational demos, ROT13 | Educational cryptanalysis teaching |

| Key Example | ROT13 (shift 13) | Using keyword "ZEBRA" |

When to Use Which (Educational Context):

Use Caesar Cipher for:

- Introducing absolute beginners to substitution concepts

- Demonstrating the simplest possible encryption

- Quick manual encoding/decoding exercises

- ROT13 for casual online obfuscation

Use Keyword Cipher for:

- Teaching frequency analysis techniques

- Demonstrating cryptanalysis methods

- Providing slightly more realistic historical context

- Understanding monoalphabetic limitations

Important: Neither should ever be used for real security—both are trivially breakable by modern standards.

5.2 Keyword Cipher vs Vigenère Cipher

⚠️ Critical Misconception Alert

A common and serious misconception confuses keyword cipher with Vigenère cipher because both use "keywords." However, they are fundamentally different cipher types with completely different mechanisms:

- Keyword cipher: Monoalphabetic (single fixed substitution alphabet)

- Vigenère cipher: Polyalphabetic (multiple shifting alphabets)

How the Keyword is Used:

- Keyword cipher: Generates ONE cipher alphabet used for the entire message

- Vigenère cipher: Determines WHICH alphabet to use for EACH letter position

This is not a subtle difference—it represents a fundamental distinction in cipher design and security.

Detailed Comparison Table:

| Feature | Keyword Cipher | Vigenère Cipher |

|---|---|---|

| Cipher Type | Monoalphabetic substitution | Polyalphabetic substitution |

| Number of Alphabets | 1 fixed alphabet | Multiple (equals key length) |

| How Keyword Used | Generates single cipher alphabet | Selects tableau row for each letter |

| Same Letter Encryption | A always → same letter (e.g., Z) | A → different letters (Z, then G, then M, ...) |

| Example | HELLO → GJKKL (both L's → K) | HELLO → GIMCO (L→M first time, L→C second time) |

| Key Reuse | One-time alphabet generation | Repeats for each letter position |

| Frequency Analysis | Highly vulnerable | Resistant (flattens distribution) |

| Security Level | Low | Medium (for classical era) |

| Breaking Method | Direct frequency analysis | Kasiski examination + frequency analysis |

| Breaking Difficulty | Easy (50-100 chars) | Moderate (needs more ciphertext + key length determination) |

| Historical Period | 15th-19th century | 16th-19th century (peak: 18th-19th) |

| Historical Reputation | Never considered unbreakable | "Le chiffre indéchiffrable" (until 1863) |

| Typical Use | Diplomatic correspondence, nomenclators | Military communications, sensitive information |

| Breaking Discovery | Known vulnerable since Al-Kindi (850 AD) | Babbage (unpublished 1854), Kasiski (1863) |

Visual Demonstration of the Difference:

Keyword Cipher (using keyword "ZEBRA"):

Plaintext: H E L L O

Cipher: G J K K L

Notice: Both L's encrypt to K (demonstrates monoalphabetic property)

Vigenère Cipher (using keyword "ZEBRA"):

Plaintext: H E L L O

Key: Z E B R A

Cipher: G I M C O

Notice: The two L's encrypt to M and C respectively (demonstrates polyalphabetic property)

This concrete example shows the fundamental difference: same input letter always produces the same output in keyword cipher, but different outputs in Vigenère cipher.

Why the Confusion Exists:

- Terminology: Both use the word "keyword"

- "Keyword Shift Cipher": Some websites (e.g., dcode.fr) call a Vigenère variant "keyword shift cipher"—this is NOT the same as keyword cipher

- Historical Overlap: Both were used during the same historical period

- Keyword Role: Keywords play important roles in both, but serve completely different purposes

Security Implications:

The distinction critically affects security:

- Keyword cipher: One frequency analysis attack breaks it completely

- Vigenère: Must first determine key length (Kasiski examination), then break each alphabet individually

Historical Impact:

- Keyword cipher: Routinely broken by government cryptanalysts since the 16th century

- Vigenère: Considered "the indecipherable cipher" (le chiffre indéchiffrable) until Kasiski published his method in 1863

Evolution: The transition from monoalphabetic to polyalphabetic ciphers represented a major cryptographic advancement. Understanding this distinction is crucial for comprehending the history of cryptography.

5.3 Monoalphabetic vs Polyalphabetic Ciphers

Monoalphabetic Substitution Ciphers:

Use a single, fixed substitution alphabet throughout the entire message:

- Same plaintext letter always maps to same ciphertext letter

- Preserves the frequency distribution of the plaintext language

- Highly vulnerable to frequency analysis

- Large theoretical key space doesn't help security

Examples:

- Caesar cipher (ROT-n shift)

- Keyword cipher

- Atbash cipher (reverse alphabet: A→Z, B→Y, etc.)

- Random substitution cipher

Polyalphabetic Substitution Ciphers:

Use multiple substitution alphabets, alternating based on key position:

- Same plaintext letter maps to different ciphertext letters at different positions

- Flattens the frequency distribution (makes analysis harder)

- Resistant to simple frequency analysis

- Security depends on key length and implementation

Examples:

- Vigenère cipher

- Beaufort cipher

- Autokey cipher

- Running key cipher

Keyword Cipher's Position in Cryptographic Evolution:

The keyword cipher represents the most complex monoalphabetic cipher but remains fundamentally weaker than even the simplest polyalphabetic cipher. Understanding this helps explain the historical transition:

Cryptographic Evolution Path:

- Ancient Era: Simple transposition and Caesar shift

- Medieval Era: More complex monoalphabetic substitution

- Renaissance: Keyword ciphers and nomenclators (peak monoalphabetic)

- 16th Century: Polyalphabetic ciphers introduced (Alberti, Vigenère)

- Modern Era: Mechanical and electrical cipher machines, then digital encryption

5.4 Security Comparison Summary

Classical Cipher Security Ranking (Weakest to Strongest):

1. Caesar Cipher - Security Rating: 0/10

- Key space: 25 possible shifts

- Break time: Seconds (brute force—try all 25)

- Weakness: Trivial key space, completely impractical

- Historical use: Ancient Rome, educational only

2. Keyword Cipher - Security Rating: 1/10

- Key space: 26! ≈ 2⁸⁸ (theoretical, but irrelevant)

- Break time: Minutes with frequency analysis

- Weakness: Monoalphabetic, preserves frequency patterns

- Historical use: 15th-19th century diplomacy

3. Random Substitution - Security Rating: 1/10

- Key space: 26! (same as keyword)

- Break time: Minutes to hours (frequency analysis)

- Weakness: Large key space doesn't overcome monoalphabetic vulnerability

- Note: Keyword cipher is a structured version of this

4. Vigenère Cipher - Security Rating: 3/10 (for classical era)

- Key space: 26^k where k = key length

- Break time: Hours to days (Kasiski + frequency analysis)

- Weakness: Breakable once key length determined

- Historical use: 16th-19th century, "indecipherable" until 1863

5. One-Time Pad - Security Rating: 10/10 (perfect secrecy)

- Key space: Effectively infinite (truly random key as long as message)

- Break time: Mathematically impossible (information-theoretically secure)

- Requirements: Perfect random key, never reused, same length as message

- Practical limitations: Key distribution, key length, impossibility of key reuse

6. Modern Encryption (AES, RSA) - Security Rating: 10/10

- Key space: 2¹²⁸ to 2²⁰⁴⁸ depending on algorithm

- Break time: Computationally infeasible with current technology

- Security basis: Mathematical complexity (factoring, discrete logarithm problems)

- Practical use: All modern secure communications

Key Insight: All classical ciphers (including keyword cipher) are completely insecure by modern standards. However, they represent crucial evolutionary steps in cryptographic thinking. The keyword cipher demonstrates how even a large theoretical key space (26! ≈ 2⁸⁸ combinations) provides no practical security when the underlying algorithm has fundamental structural weaknesses like monoalphabetic substitution.

Conclusion: The keyword cipher occupies an important middle ground in cryptographic history: more sophisticated than simple shift ciphers but fundamentally limited by its monoalphabetic nature. Understanding its strengths and weaknesses illuminates the entire evolution of cryptographic science.

6. Implementation Guide

6.1 Algorithm Pseudocode

FUNCTION removeDuplicates(keyword):

seen = empty set

result = empty string

FOR each character in keyword.toUpperCase():

IF character is letter AND character not in seen:

Add character to result

Add character to seen

RETURN result

FUNCTION generateCipherAlphabet(keyword):

processedKeyword = removeDuplicates(keyword)

normalAlphabet = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"

cipherAlphabet = processedKeyword

FOR each letter in normalAlphabet:

IF letter not in processedKeyword:

Append letter to cipherAlphabet

RETURN cipherAlphabet

FUNCTION encrypt(plaintext, keyword):

cipherAlphabet = generateCipherAlphabet(keyword)

normalAlphabet = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"

result = empty string

FOR each character in plaintext:

IF character is letter:

isUpper = character is uppercase

index = position of character.toUpperCase() in normalAlphabet

encrypted = cipherAlphabet[index]

IF isUpper:

result += encrypted

ELSE:

result += encrypted.toLowerCase()

ELSE:

result += character // Pass through spaces, punctuation

RETURN result

FUNCTION decrypt(ciphertext, keyword):

cipherAlphabet = generateCipherAlphabet(keyword)

normalAlphabet = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"

result = empty string

FOR each character in ciphertext:

IF character is letter:

isUpper = character is uppercase

index = position of character.toUpperCase() in cipherAlphabet

decrypted = normalAlphabet[index]

IF isUpper:

result += decrypted

ELSE:

result += decrypted.toLowerCase()

ELSE:

result += character

RETURN result

6.2 Python Implementation

def remove_duplicates(keyword):

"""Remove duplicate letters from keyword while preserving order."""

seen = set()

result = []

for char in keyword.upper():

if char.isalpha() and char not in seen:

seen.add(char)

result.append(char)

return ''.join(result)

def generate_cipher_alphabet(keyword):

"""Generate cipher alphabet from keyword."""

processed_keyword = remove_duplicates(keyword)

normal_alphabet = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

# Build cipher alphabet: keyword + remaining letters

cipher_alphabet = processed_keyword

for letter in normal_alphabet:

if letter not in processed_keyword:

cipher_alphabet += letter

return cipher_alphabet

def keyword_cipher_encrypt(plaintext, keyword):

"""Encrypt plaintext using keyword cipher."""

cipher_alphabet = generate_cipher_alphabet(keyword)

normal_alphabet = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

result = []

for char in plaintext:

if char.isalpha():

is_upper = char.isupper()

index = normal_alphabet.index(char.upper())

encrypted = cipher_alphabet[index]

result.append(encrypted if is_upper else encrypted.lower())

else:

result.append(char) # Preserve spaces and punctuation

return ''.join(result)

def keyword_cipher_decrypt(ciphertext, keyword):

"""Decrypt ciphertext using keyword cipher."""

cipher_alphabet = generate_cipher_alphabet(keyword)

normal_alphabet = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

result = []

for char in ciphertext:

if char.isalpha():

is_upper = char.isupper()

index = cipher_alphabet.index(char.upper())

decrypted = normal_alphabet[index]

result.append(decrypted if is_upper else decrypted.lower())

else:

result.append(char)

return ''.join(result)

# Example usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

keyword = "ZEBRA"

plaintext = "Hello World"

# Encrypt

ciphertext = keyword_cipher_encrypt(plaintext, keyword)

print(f"Plaintext: {plaintext}")

print(f"Keyword: {keyword}")

print(f"Ciphertext: {ciphertext}") # Output: "Gjkkl Vloka"

# Decrypt

decrypted = keyword_cipher_decrypt(ciphertext, keyword)

print(f"Decrypted: {decrypted}") # Output: "Hello World"

# Display cipher alphabet

cipher_alpha = generate_cipher_alphabet(keyword)

print(f"\nNormal: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ")

print(f"Cipher: {cipher_alpha}")

6.3 JavaScript Implementation

function removeDuplicates(keyword) {

const seen = new Set();

const result = [];

for (const char of keyword.toUpperCase()) {

if (/[A-Z]/.test(char) && !seen.has(char)) {

seen.add(char);

result.push(char);

}

}

return result.join('');

}

function generateCipherAlphabet(keyword) {

const processed = removeDuplicates(keyword);

let cipher = processed;

const normalAlphabet = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ';

for (const letter of normalAlphabet) {

if (!processed.includes(letter)) {

cipher += letter;

}

}

return cipher;

}

function keywordCipherEncrypt(plaintext, keyword) {

const cipherAlphabet = generateCipherAlphabet(keyword);

const normalAlphabet = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ';

return plaintext.split('').map(char => {

if (/[a-zA-Z]/.test(char)) {

const isUpper = char === char.toUpperCase();

const index = normalAlphabet.indexOf(char.toUpperCase());

const encrypted = cipherAlphabet[index];

return isUpper ? encrypted : encrypted.toLowerCase();

}

return char; // Preserve non-alphabetic characters

}).join('');

}

function keywordCipherDecrypt(ciphertext, keyword) {

const cipherAlphabet = generateCipherAlphabet(keyword);

const normalAlphabet = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ';

return ciphertext.split('').map(char => {

if (/[a-zA-Z]/.test(char)) {

const isUpper = char === char.toUpperCase();

const index = cipherAlphabet.indexOf(char.toUpperCase());

const decrypted = normalAlphabet[index];

return isUpper ? decrypted : decrypted.toLowerCase();

}

return char;

}).join('');

}

// Example usage

const keyword = "ZEBRA";

const plaintext = "Hello World";

const encrypted = keywordCipherEncrypt(plaintext, keyword);

console.log(`Plaintext: ${plaintext}`);

console.log(`Keyword: ${keyword}`);

console.log(`Ciphertext: ${encrypted}`); // "Gjkkl Vloka"

const decrypted = keywordCipherDecrypt(encrypted, keyword);

console.log(`Decrypted: ${decrypted}`); // "Hello World"

// Display cipher alphabet

const cipherAlpha = generateCipherAlphabet(keyword);

console.log(`\nNormal: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ`);

console.log(`Cipher: ${cipherAlpha}`);

6.4 Common Coding Mistakes and Best Practices

Common Mistakes:

- Not Removing Duplicates: Forgetting to filter repeated letters from the keyword creates an invalid cipher alphabet with missing letters

- Case Handling: Not preserving the original case of plaintext characters in the output

- Special Characters: Attempting to encrypt non-alphabetic characters instead of passing them through unchanged

- Inefficient Decryption: Using linear search instead of creating a reverse lookup structure for O(1) decryption

- Empty Keyword: Not validating that the keyword contains at least one letter

- Index Errors: Not handling edge cases where characters might not be found in the alphabet

Best Practices:

-

Input Validation:

- Check that keyword is not empty and contains alphabetic characters

- Validate that all characters in plaintext are handled appropriately

- Consider normalizing input (e.g., converting to uppercase)

-

Efficient Data Structures:

- For frequent operations, use hash maps/dictionaries for O(1) lookup time

- Consider pre-computing reverse cipher alphabet for decryption

- Cache cipher alphabet generation if encrypting multiple messages with same keyword

-

Case Preservation:

- Always preserve the original case of input text

- Process in uppercase internally, convert back as needed

- Document case-handling behavior clearly

-

Special Character Handling:

- Define clear policy: pass through unchanged or remove

- Handle spaces, punctuation, numbers consistently

- Document the behavior in function comments

-

Testing:

- Test with edge cases: empty strings, single characters, all uppercase, all lowercase

- Test special characters: spaces, punctuation, numbers

- Verify encryption/decryption round-trip (encrypt then decrypt = original)

- Test keywords with duplicates (BASEBALL → BASEL)

- Test keywords without duplicates (CIPHER)

-

Code Documentation:

- Comment algorithm steps clearly

- Provide examples in docstrings

- Explain non-obvious design decisions

Performance Considerations:

- Alphabet Generation: O(n) where n = 26 (alphabet size) - very fast

- Encryption/Decryption: O(m) where m = message length - linear time

- Space Complexity: O(1) - constant space for alphabet storage

- Overall: Very efficient even for long messages; performance bottlenecks unlikely

Security Reminder: Remember that keyword cipher provides no real security. These implementations are for educational purposes only. Never use keyword cipher to protect actual sensitive information.

7. Modern Educational Applications

7.1 Teaching Classical Cryptography

Today, keyword ciphers serve primarily as educational tools in university cryptography courses and secondary school mathematics classes. They provide an accessible introduction to several fundamental concepts:

Core Concepts Taught:

- Symmetric encryption principles: Same key for encryption and decryption

- Monoalphabetic substitution: Single fixed mapping between alphabets

- Key-based transformations: How a secret key controls the cipher operation

- Historical context: Understanding how encryption evolved over centuries

Instructors use keyword ciphers to demonstrate that encryption existed long before computers, helping students grasp that cryptography is rooted in mathematical and logical principles rather than just computational power.

7.2 Introduction to Cryptanalysis

The keyword cipher's vulnerability makes it an ideal teaching tool for cryptanalysis fundamentals:

Skills Developed:

- Frequency analysis techniques: Learning to count and analyze letter distributions

- Pattern recognition: Identifying common words and letter combinations (THE, AND, -ING)

- Statistical analysis: Understanding how language statistics expose cipher weaknesses

- Logical deduction: Using partial information to infer complete solutions

- Systematic methodology: Following structured approaches to problem-solving

Students gain hands-on experience with the same techniques that professional cryptanalysts have used for centuries, building intuition about cipher strength and weakness.

7.3 Programming Exercises

Computer science courses frequently assign keyword cipher implementation as a practical coding exercise:

Learning Objectives:

- Algorithm implementation: Translating specifications into working code

- Data structures: Using hash maps/dictionaries for efficient letter mapping

- String manipulation: Processing text character-by-character

- Input/output handling: Reading user input, displaying results

- Testing and debugging: Validating correctness through test cases

These exercises typically appear in introductory programming courses, data structures classes, and algorithms courses as examples of practical cryptographic algorithms.

7.4 CTF (Capture The Flag) Challenges

Keyword ciphers appear frequently in Capture The Flag (CTF) cybersecurity competitions, particularly in beginner-level cryptography challenges:

Common CTF Applications:

- Cipher identification practice: Recognizing substitution cipher patterns in ciphertext

- Manual breaking exercises: Applying frequency analysis to recover flags

- Automated tool usage: Learning to use cryptanalysis tools

- Forensics challenges: Finding hidden encrypted messages in files or images

CTF competitions provide gamified learning experiences where participants compete to solve challenges, making cryptography education more engaging and competitive.

7.5 Puzzle and Entertainment Applications

Beyond formal education, keyword ciphers remain popular in recreational contexts:

Popular Uses:

- Geocaching: Treasure hunt coordinates encrypted with keyword ciphers

- Escape rooms: Puzzle solutions hidden in cipher messages

- Alternate Reality Games (ARG): Plot clues encoded with classical ciphers

- Cryptogram puzzles: Newspaper and magazine puzzles using substitution ciphers

- Mystery novels: Authors incorporating cipher puzzles into storylines

These recreational applications keep classical ciphers alive in popular culture while challenging participants to apply problem-solving skills.

7.6 Available Tools and Resources

Online Educational Tools:

- Interactive encoder/decoder websites (dCode.fr, CyberChef, CryptoCorner)

- Automated frequency analysis tools

- Step-by-step cryptanalysis tutorials

- Historical cipher collections and museums

Educational Resources:

- Books: "The Code Book" by Simon Singh, "Cryptanalysis" by Helen Fouché Gaines

- Online courses: Coursera, Khan Academy cryptography modules

- Practice problem sets: Project Euler, CryptoHack challenges

- Video tutorials: YouTube channels dedicated to cryptography education

Academic Resources:

- University course materials (MIT OCW, Stanford online)

- Research papers on classical cryptography

- Historical document archives

- Cryptography museums and exhibits

While keyword ciphers cannot protect modern communications, their value as educational tools ensures they remain relevant in teaching the foundations of cryptography and cryptanalysis.

8. Practice Exercises and Worksheets

8.1 Encryption Exercises

Exercise 1: Basic Encryption (Beginner)

- Keyword: CIPHER

- Plaintext: MEET ME AT DAWN

- Task: Encrypt this message using the keyword cipher

- Expected difficulty: 5-10 minutes

Exercise 2: Duplicate Removal Practice (Beginner)

- Keyword: MISSISSIPPI

- Tasks:

- Remove duplicate letters from the keyword

- Generate the complete cipher alphabet

- Encrypt: HELLO WORLD

- Expected difficulty: 10-15 minutes

Exercise 3: Long Message Encryption (Intermediate)

- Keyword: CRYPTOGRAPHY

- Plaintext: THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG

- Task: Encrypt the entire message and observe letter frequency patterns

- Expected difficulty: 15-20 minutes

8.2 Decryption Challenges

Challenge 1: Known Keyword Decryption (Beginner)

- Keyword: ZEBRA

- Ciphertext: CJJJ ZS LMBJ VA ZOJ RFPBLUJOAR

- Task: Decrypt the message

- Hint: Use the same cipher alphabet generation process

- Expected difficulty: 10 minutes

Challenge 2: Unknown Keyword - Short Message (Intermediate)

- Ciphertext: QIJ BZQQJA VL MJBZSVLY

- Length: 21 characters

- Hint: The keyword is a common four-letter animal

- Task: Use frequency analysis to break the cipher and identify the keyword

- Expected difficulty: 20-30 minutes

Challenge 3: Unknown Keyword - Full Cryptanalysis (Advanced)

- Ciphertext:

QIJ PJZVLA BJVIJA VQ QIJ MJGVQQVQD TY QIJ YVYQJJQQI BJJQZMA VQ VJQQJQQA QIJMA JWJ KJJLKJ QIZNLIQ ZQTSLVA SXJMA VQBTLLVMKJ - Length: 151 characters

- Hint: None provided

- Task: Complete cryptanalysis using frequency analysis

- Expected difficulty: 45-60 minutes

8.3 Cryptanalysis Practice

Practice 1: Frequency Analysis Exercise

- Ciphertext: MJNNX VXENC

- Task: Count letter frequencies and identify the most likely substitutions for E, T, A

- Expected difficulty: 15 minutes

Practice 2: Known-Plaintext Attack

- Known: "THE" appears in the plaintext as "QIJ" in ciphertext

- Partial ciphertext: QIJ PJZVLA ...

- Task: Use the known plaintext to derive additional letter mappings

- Expected difficulty: 20 minutes

Practice 3: Keyword Extraction

- Given cipher alphabet: CIPHERABDFGJKLMNOQSTUVWXYZ

- Task: Identify the original keyword from the cipher alphabet pattern

- Expected difficulty: 10 minutes

8.4 Solutions and Explanations

Exercise 1 Solution:

- Cipher alphabet: CIPHERABDFGJKLMNOQSTUVWXYZ

- Ciphertext: IDDM ID HM PHVK

Exercise 2 Solution:

- Processed keyword: MISP (removes duplicates)

- Cipher alphabet: MISPABCDEFGHJKLNOQRTUVWXYZ

- HELLO WORLD → GDKKL VLQKC

Challenge 1 Solution:

- Plaintext: FLEE AT ONCE WE ARE DISCOVERED

Challenge 2 Solution:

- Keyword: BEAR (or similar four-letter animal)

- Frequency analysis reveals high frequency of J, Q, V

Challenge 3 Solution:

- This is the complete example from Section 4.4

- Keyword: CIPHER

- Plaintext: THE PEOPLE BELIEVE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY IN VIGENERE THEIR EYE PEOPLE THOUGHT ABOUT OVER IMPOSSIBLE

Learning Points:

- Frequency analysis becomes more accurate with longer ciphertexts

- Common words like THE, AND provide strong clues

- Pattern recognition (doubled letters, common endings) speeds analysis

- Systematic methodology is crucial for successful cryptanalysis

9. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Basic Concepts

Q: What is a keyword cipher?

A: A keyword cipher is a monoalphabetic substitution cipher that uses a keyword to generate a mixed cipher alphabet. The keyword (with duplicate letters removed) is placed at the beginning of the cipher alphabet, followed by the remaining unused letters in alphabetical order. Each plaintext letter always maps to the same ciphertext letter throughout the message.

Q: How does keyword cipher work?

A: It works by creating a substitution alphabet from a keyword. First, remove duplicate letters from the keyword. Then place the processed keyword at the start of the cipher alphabet and append the remaining letters in alphabetical order. Use this cipher alphabet to substitute each plaintext letter with its corresponding cipher letter.

Q: What is monoalphabetic substitution cipher?

A: A monoalphabetic substitution cipher uses a single, fixed substitution alphabet for the entire message. Each plaintext letter always maps to the same ciphertext letter. Keyword cipher, Caesar cipher, and Atbash are all examples of monoalphabetic ciphers. This fixed mapping makes them vulnerable to frequency analysis.

Q: What is the keyword cipher algorithm?

A: The algorithm consists of: (1) Remove duplicate letters from keyword, (2) Place processed keyword at alphabet start, (3) Append remaining letters in order, (4) Create mapping from normal to cipher alphabet, (5) Substitute each plaintext letter, (6) Preserve non-letter characters unchanged.

Tutorial & Implementation

Q: How to create keyword cipher?

A: Follow these steps: (1) Choose a keyword, (2) Remove duplicate letters (e.g., BASEBALL → BASEL), (3) Place the processed keyword at the alphabet start, (4) Add remaining unused letters in alphabetical order, (5) Use this cipher alphabet for letter-by-letter substitution.

Q: How to remove duplicate letters?

A: Iterate through the keyword keeping only the first occurrence of each letter. Example: MISSISSIPPI → MISP (keep first M, first I, first S, first P; skip all subsequent duplicates).

Q: What is an example of keyword cipher?

A: Using keyword "ZEBRA": The cipher alphabet becomes ZEBRACKDFGHIJLMNOPQSTUVWXY. "HELLO" encrypts to "GJKKL" because H→G, E→J, L→K, L→K, O→L.

Q: How to encrypt/decrypt with keyword cipher?

A: Encrypt: Map each plaintext letter to its corresponding position in the cipher alphabet. Decrypt: Reverse the process by mapping cipher letters back to normal alphabet positions using the same keyword-generated alphabet.

Q: How to implement keyword cipher in Python?

A: See Section 6.2 for a complete Python implementation with code examples showing encryption, decryption, and cipher alphabet generation.

Security & Cryptanalysis

Q: How to break keyword cipher?

A: The primary method is frequency analysis: (1) Count letter frequencies in the ciphertext, (2) Compare to English letter frequencies (E=12.7%, T=9.1%, A=8.2%), (3) Map the most common ciphertext letters to the most common English letters, (4) Look for common words (THE, AND, OF), (5) Iteratively refine the mapping until plaintext emerges. Typically requires 50-100 characters of ciphertext.

Q: What are the vulnerabilities?

A: As a monoalphabetic cipher, keyword cipher is fundamentally vulnerable to frequency analysis because it preserves the frequency distribution of the plaintext language. The same letter always encrypts to the same letter, revealing statistical patterns regardless of keyword complexity or length.

Q: What is frequency analysis?

A: Frequency analysis is a cryptanalysis method based on studying the frequency distribution of letters (or letter groups) in ciphertext. By comparing ciphertext frequencies to known language frequencies (E is most common in English at 12.7%), cryptanalysts can deduce the substitution mapping. First systematically described by Al-Kindi around 850 AD.

Q: How to extract keyword from ciphertext?

A: If you have the cipher alphabet (reconstructed through frequency analysis), look for consecutive letters at the end (e.g., ...TUVWXYZ), which indicates where the keyword ends. The beginning of the cipher alphabet reveals the keyword. Example: ZEBRACKDFGHIJLMNOPQSTUVWXY suggests keyword ZEBRA.

Q: How secure is keyword cipher?

A: Keyword cipher provides no practical security by modern standards. Despite a theoretical key space of 26! (approximately 2⁸⁸ combinations), it can be broken manually with 50-100 characters of ciphertext using frequency analysis, and broken by computer in seconds. Never use it to protect real information.

Comparisons

Q: Keyword cipher vs Caesar cipher?

A: Both are monoalphabetic substitution ciphers vulnerable to frequency analysis. Caesar uses a simple numeric shift (key space: 25), while keyword uses a word to create a mixed alphabet (key space: ~2⁸⁸ theoretical). Both are insecure by modern standards, but keyword cipher is slightly more complex and requires frequency analysis rather than simple brute force.

Q: Keyword cipher vs Vigenère cipher?

A: Critical difference: Keyword cipher is monoalphabetic (single fixed alphabet), while Vigenère is polyalphabetic (multiple shifting alphabets). In keyword cipher, the same letter always encrypts the same way. In Vigenère, the same letter encrypts differently each time based on key position. Vigenère is significantly more secure and was considered "indecipherable" until 1863.

Q: Monoalphabetic vs polyalphabetic?

A: Monoalphabetic uses one substitution alphabet (vulnerable to frequency analysis). Polyalphabetic uses multiple alphabets (resistant to simple frequency analysis). Examples: Keyword cipher = monoalphabetic, Vigenère = polyalphabetic. This distinction represents a major advancement in cryptographic history.

History

Q: What is the history of keyword cipher?

A: Keyword cipher emerged in 15th-century Renaissance Europe as an evolution from simpler Caesar shift ciphers. It was widely used in diplomatic and military communications from the 16th-18th centuries, often integrated into nomenclator systems (substitution + codebook). The cipher declined in the 19th century with the rise of polyalphabetic ciphers and better-understood frequency analysis techniques.

Q: When was keyword cipher invented?

A: Keyword-based substitution ciphers emerged during the Renaissance period (15th century), approximately 1500 years after the Caesar cipher. They represented an evolutionary step toward more sophisticated monoalphabetic systems driven by the complex diplomatic needs of Renaissance Italian city-states.

Q: What is a nomenclator cipher?

A: A nomenclator is a hybrid cipher system combining keyword-based monoalphabetic substitution with a codebook for common words, names, and phrases. It was the standard diplomatic cipher from the 15th to 18th centuries. Famous example: Louis XIV's Great Cipher, which remained unbroken for 200 years until 1890.

Q: What ciphers were used in Renaissance?

A: Renaissance cryptography included simple substitution ciphers, keyword-based substitution, nomenclators (substitution + codebook hybrids), and Leon Battista Alberti's cipher disk (1466), which introduced the concept of polyalphabetic ciphers and influenced the eventual development of the Vigenère cipher.

Q: Who was Leon Battista Alberti?

A: Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) was an Italian Renaissance polymath who invented the cipher disk in 1466, creating the first practical polyalphabetic cipher system. His work profoundly influenced cryptographic evolution from simple monoalphabetic substitution toward more complex encryption systems. He is often called the "Father of Western Cryptography."

Q: What was Louis XIV's Great Cipher?

A: The Great Cipher (Grand Chiffre) was an extremely complex nomenclator created by the Rossignol family for Louis XIV in the 17th century. It used 587 symbols representing syllables, complete words, and included nulls and traps. It protected French state secrets for over 200 years until cryptanalyst Étienne Bazeries broke it in 1890-1893, revealing historical secrets including clues about the "Man in the Iron Mask."

10. Conclusion and Further Resources

10.1 Key Takeaways

The keyword cipher represents a crucial chapter in the evolution of cryptography, bridging ancient simple ciphers and modern encryption systems. Understanding its history, mechanics, and vulnerabilities provides essential insights into cryptographic principles:

Historical Significance:

- Emerged in 15th-century Renaissance Europe from the need for diplomatic security

- Served as the foundation for nomenclator systems used for 300+ years

- Played critical roles in historical events (Mary Queen of Scots execution, Louis XIV's secrets)

- Demonstrated both the power and limitations of monoalphabetic substitution

Technical Understanding:

- Uses a keyword to generate a mixed substitution alphabet

- Monoalphabetic nature preserves frequency patterns

- Large theoretical key space (26! ≈ 2⁸⁸) provides no practical security

- Vulnerable to frequency analysis with 50-100 characters of ciphertext

- Can be broken manually in minutes or by computer in seconds

Cryptographic Evolution:

- Represents the peak of monoalphabetic cipher complexity

- Demonstrated that structural weakness matters more than key space size

- Led to development of polyalphabetic ciphers (Vigenère, Alberti)

- Influenced modern understanding of cipher security requirements

Modern Relevance:

- Educational tool for teaching cryptography and cryptanalysis fundamentals

- Programming exercise for learning algorithms and data structures

- Historical case study in the arms race between encryption and cryptanalysis

- Recreational application in puzzles, games, and CTF competitions

Security Lesson: The keyword cipher's history teaches us that complexity alone doesn't guarantee security. A cipher must be fundamentally sound in its design—large key spaces cannot compensate for structural weaknesses like monoalphabetic substitution's preservation of frequency patterns.

10.2 Related Ciphers to Explore

To deepen your understanding of classical and modern cryptography, explore these related cipher systems:

Simpler Ciphers:

- Caesar Cipher: The simplest substitution cipher, using a fixed shift

- Atbash Cipher: Reverse alphabet substitution (A↔Z, B↔Y, etc.)

- ROT13: Caesar cipher with shift 13, used for casual online obfuscation

More Complex Classical Ciphers:

- Vigenère Cipher: Polyalphabetic substitution using repeated keyword

- Playfair Cipher: Digraph substitution using 5×5 letter matrix

- Hill Cipher: Matrix-based polygraphic substitution

- Autokey Cipher: Self-synchronizing polyalphabetic cipher

Historical Systems:

- Nomenclator: Keyword substitution combined with codebook

- Enigma Machine: WWII rotor-based mechanical cipher

- Purple Cipher: Japanese diplomatic cipher machine

Modern Cryptography:

- DES/3DES: Historical symmetric block ciphers

- AES: Current standard for symmetric encryption

- RSA: Public-key cryptography based on factorization

- Elliptic Curve Cryptography: Modern public-key systems

10.3 Recommended Reading and Resources

Books:

- "The Code Book" by Simon Singh: Accessible history of cryptography from ancient ciphers to quantum cryptography

- "Cryptanalysis" by Helen Fouché Gaines: Classic text on solving classical ciphers

- "Applied Cryptography" by Bruce Schneier: Comprehensive guide to cryptographic algorithms and protocols

- "The Codebreakers" by David Kahn: Definitive comprehensive history of cryptography

Online Resources:

- CrypTool: Free educational software for cryptography and cryptanalysis

- Khan Academy: Cryptography video courses and interactive exercises

- Coursera/edX: University-level cryptography courses

- CryptoHack: Interactive platform for learning modern cryptography

Historical Resources:

- National Archives: Historical cipher documents and declassified materials

- Crypto Museum: Online museum of cipher machines and devices

- Simon Singh's Cipher Challenge: Historical cipher-breaking competition archive

- The Black Chamber: Historical cryptanalysis case studies

Academic Papers:

- Search Google Scholar for "classical cryptography," "substitution cipher analysis," "historical ciphers"

- University cryptography course materials (MIT OCW, Stanford online)

- Research on automated cryptanalysis techniques

10.4 Interactive Tools

Practice your keyword cipher skills with these online tools:

Encryption/Decryption Tools:

- CaesarCipher.org: Keyword cipher online tool with educational explanations

- dCode.fr: Comprehensive cipher tools including keyword cipher encoder/decoder

- CyberChef: Versatile cryptographic Swiss Army knife

- Crypto Corner: Interactive educational cryptography tools

Cryptanalysis Tools:

- Frequency Analysis Tools: Automatic letter frequency calculators

- Pattern Finders: Tools to identify repeated sequences and common words

- Substitution Solvers: Automated cryptanalysis with hints and assistance

Historical Simulations:

- Cipher disk simulators: Virtual versions of historical cipher devices

- Historical document databases: Practice breaking real historical ciphers

- Cipher challenges and competitions: Test your skills against others

10.5 Final Thoughts

The keyword cipher stands as a testament to human ingenuity in the pursuit of secrecy and the eternal struggle between those who protect information and those who seek to reveal it. While obsolete for practical security, it remains a powerful educational tool and a window into the fascinating history of cryptography.

From the diplomatic intrigues of Renaissance Italy to the breaking of Mary Queen of Scots' cipher, from Louis XIV's "unbreakable" Great Cipher to the Civil War cipher disks, the keyword cipher has witnessed and influenced the course of history. Its eventual vulnerability to frequency analysis taught cryptographers that true security requires more than just complexity—it demands fundamental soundness in design.

Today, as we use AES, RSA, and elliptic curve cryptography to protect our digital lives, we stand on the shoulders of the Renaissance cryptographers who developed keyword ciphers and the cryptanalysts who broke them. Their legacy lives on not in the algorithms themselves, but in the principles they established: the importance of key secrecy, the power of statistical analysis, and the eternal truth that security through obscurity provides no real protection.

Whether you're a student learning cryptography fundamentals, a programmer implementing classical algorithms, a history enthusiast exploring diplomatic intrigues, or a puzzle solver seeking challenging cryptograms, the keyword cipher offers valuable lessons. It reminds us that even the most sophisticated systems of their time eventually fall to determined analysis, and that true security requires constant vigilance, innovation, and adaptation to new threats.

The keyword cipher may no longer protect secrets, but it continues to unlock understanding—and that may be its greatest contribution of all.