The caesar cipher history begins over 2,000 years ago with one of the oldest and most famous encryption methods ever documented. Named after the Roman military leader Julius Caesar, this simple yet ingenious technique has survived for over two millennia. It evolved from a tool of ancient warfare to a beloved educational gateway into the world of codes and ciphers.

In this comprehensive exploration of caesar cipher history, we trace its origins in the battlefields of ancient Rome. We examine how it works, discover why it was eventually broken, and uncover surprising modern cases where this ancient cipher still made headlines. Whether you're a cryptography enthusiast, history buff, or simply curious about how secrets were kept in ancient times, this journey through time reveals why the Caesar cipher remains relevant today.

What is the Caesar Cipher?

The Caesar cipher is a type of substitution cipher in which each letter in the plaintext is replaced by a letter a fixed number of positions down the alphabet. Named after Julius Caesar who used a shift of 3 to protect military communications around 100 BC, it remains one of the simplest and most widely known encryption techniques in the world. This foundational method in caesar cipher history demonstrates the earliest documented systematic approach to secret communication.

The Basic Mechanism

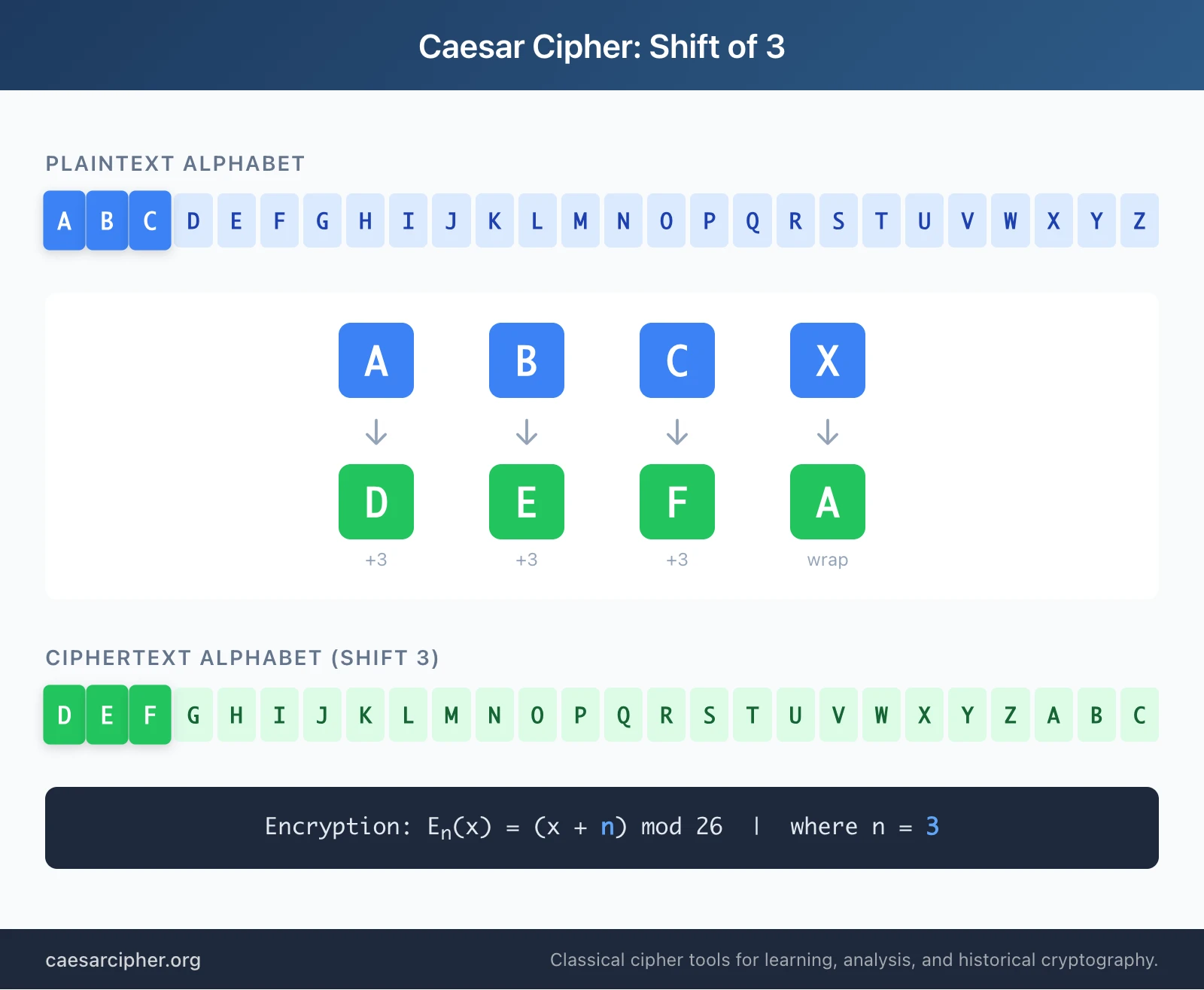

At its core, the Caesar cipher operates on a straightforward principle: every letter in your message gets shifted by the same amount. If you choose a shift of 3 (as Caesar did), the letter A becomes D, B becomes E, C becomes F, and so on through the alphabet. This simple transformation created the foundation for all modern encryption.

When you reach the end of the alphabet, the pattern wraps around. With a shift of 3, X becomes A, Y becomes B, and Z becomes C. This wraparound ensures that every letter has a corresponding encrypted form.

Both encryption and decryption use the same key—the shift value. To decode a message, you simply shift each letter backward by the same amount. This symmetric approach made the cipher practical for military use.

Why It Matters Historically

The Caesar cipher represents the first documented encryption method in Western history. While other civilizations may have used similar techniques, the detailed accounts from Roman historians give us concrete evidence of its use in military operations. This makes caesar cipher history a crucial starting point for understanding cryptography.

More importantly, the Caesar cipher introduced fundamental concepts that underpin all of cryptography: the idea of a key, the notion of systematic transformation, and the principle that a secret message requires a shared secret to decode. These concepts would eventually evolve into the sophisticated encryption systems that protect our digital world today. Understanding this historical context helps us appreciate how far cryptography has evolved.

Who Invented the Caesar Cipher?

The Caesar cipher was invented by Julius Caesar, the Roman military leader and statesman who lived from 100-44 BC. According to the Roman historian Suetonius, writing in his "Lives of the Twelve Caesars" around 121 AD, Caesar used this cipher to protect messages of military significance during his military campaigns. This marks a pivotal moment in caesar cipher history and the broader development of secret communication.

Suetonius: Our Primary Source

Suetonius provides the earliest and most detailed account of Caesar's encryption method. In his biographical work, he wrote:

"If he had anything confidential to say, he wrote it in cipher, that is, by so changing the order of the letters of the alphabet, that not a word could be made out. If anyone wishes to decipher these, and get at their meaning, he must substitute the fourth letter of the alphabet, namely D, for A, and so with the others."

This passage clearly describes the shift-3 cipher that became Caesar's signature encryption method. Suetonius, who had access to imperial archives and served under several emperors, is considered a reliable historical source for Roman practices of the late Republic period. His documentation forms the cornerstone of what we know about caesar cipher history.

The Gallic Wars Context

The need for secure communications became particularly acute during Caesar's Gallic Wars (58-50 BC). Commanding multiple legions across hostile territory in what is now France, Belgium, and parts of Germany, Caesar faced the constant challenge of coordinating military operations across vast distances. This period represents the most active phase of caesar cipher history in practical military application.

Messages had to travel through enemy territory, carried by messengers who could be captured or killed. If a message fell into enemy hands, the consequences could be disastrous—troop positions revealed, supply routes exposed, or strategic plans compromised. The stakes of secure communication were literally life and death.

The cipher provided a solution: even if a message was intercepted, it would appear as meaningless gibberish to anyone who didn't know the system. This protection, though simple by modern standards, was revolutionary for its time.

How Did Julius Caesar Use His Cipher?

The Shift of Three

Caesar consistently used a shift of three for his encrypted communications. Under this system, the letter A becomes D, B becomes E, C becomes F, and the pattern continues through the alphabet. This specific shift value became so closely associated with Caesar that it's now the default example taught in cryptography courses.

The choice of three as the shift value may seem arbitrary, but it struck a balance between security and usability. A smaller shift might be too easy to detect, while a larger shift offered no additional security benefit given the limited methods of attack available at the time. The practical wisdom behind this choice demonstrates Caesar's strategic thinking.

The Roman historian Cassius Dio confirmed this practice, noting that Caesar's generals would know to "substitute the fourth letter of the alphabet" when decoding his messages. This standardization was crucial for effective military communication.

Military Communications

Caesar's cipher served several critical military functions. Strategic orders could be sent to generals commanding distant legions without fear that captured messengers would reveal the plans. Intelligence reports from scouts and spies could be transmitted securely. Coordination of multi-front attacks required timing that enemies shouldn't learn in advance.

The cipher wasn't used for every message—only those containing sensitive information. Routine communications likely traveled in plain Latin, while strategic secrets received the protection of encryption. This selective use demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of operational security that was centuries ahead of its time.

Why It Worked in Ancient Times

The Caesar cipher's security in ancient Rome depended on several factors that no longer apply today. Literacy rates among Rome's enemies were extremely low. The Gallic tribes and Germanic peoples Caesar fought had limited written traditions, so even an unencrypted Latin message might be incomprehensible to them.

More importantly, systematic cryptanalysis—the science of breaking codes—simply didn't exist yet. The techniques we now use to crack substitution ciphers wouldn't be developed for another nine centuries. In Caesar's time, a cipher needed only to prevent casual reading, not withstand expert analysis. This context is essential to understanding caesar cipher history and why it remained effective for so long.

Augustus's Secret Variation

Caesar's nephew Augustus, who became the first Roman Emperor, developed his own variation of the cipher that differed from his famous uncle's method in several interesting ways. This adaptation represents an important chapter in caesar cipher history, showing how the technique evolved within the Roman imperial family.

The Shift of One

According to Suetonius, Augustus used a simpler shift of just one position:

"Whenever he wrote in cipher, he wrote B for A, C for B, and the rest of the letters on the same principle, using AA for Z."

This meant A became B, B became C, and so on—a gentler transformation than Caesar's shift of three. Augustus's preference for simplicity may have reflected different security needs in peacetime imperial administration compared to active military campaigns.

Comparison with Caesar's Method

The most notable difference was Augustus's handling of the letter Z. Rather than wrapping around to A (as Caesar did with his shift-3 method), Augustus wrote "AA" to represent Z. This created a cipher that was technically not a pure substitution cipher, as it introduced a two-character replacement for one letter.

Why Augustus made this choice isn't recorded, but it suggests he found the wraparound concept either confusing or unnecessary for his purposes. His cipher was primarily used for personal correspondence rather than military communications. This distinction highlights how the application of the cipher evolved as caesar cipher history progressed from military to civilian use.

The Lost Treatise

The writer Aulus Gellius, in his work "Attic Nights," mentions an intriguing historical mystery:

"There is even a rather ingeniously written treatise by the grammarian Probus concerning the secret meaning of letters in the composition of Caesar's epistles."

This suggests that Caesar may have used more sophisticated encryption methods beyond the simple shift cipher, and that a detailed analysis of his cryptographic techniques once existed. Unfortunately, this treatise has been lost to history, leaving us to wonder what other secrets of Roman cryptography might have been revealed. This tantalizing reference reminds us that our understanding of caesar cipher history may be incomplete.

How Does the Caesar Cipher Work?

Understanding the mechanics of the Caesar cipher is straightforward, which partly explains its enduring place in caesar cipher history. Here's the step-by-step encryption process:

- Choose a shift value (the key)—traditionally 3 for Caesar's original method

- Write out the plaintext message you want to encrypt

- For each letter, count forward in the alphabet by the shift value

- Replace the original letter with the shifted letter

- When you pass Z, wrap around to A and continue counting

- Non-letter characters (spaces, numbers, punctuation) typically remain unchanged

- The resulting text is your ciphertext

The Encryption Formula

Mathematicians express the Caesar cipher using modular arithmetic:

Encryption: E_n(x) = (x + n) mod 26

In this formula, x represents the position of a letter (A=0, B=1, C=2... Z=25), n is the shift value, and "mod 26" handles the wraparound when you pass Z. This mathematical formalization came centuries after Caesar's time, but it elegantly captures the principle he discovered.

The Decryption Formula

Decryption works by reversing the process:

Decryption: D_n(x) = (x - n) mod 26

The beauty of the Caesar cipher is its symmetry: knowing the encryption key means you automatically know the decryption key. You simply shift in the opposite direction. This elegant simplicity made it practical for Roman military commanders who needed to decode messages quickly in the field.

Caesar Cipher Examples

Let's see the Caesar cipher in action with some concrete examples. These demonstrations help illustrate why the technique survived throughout caesar cipher history as an educational tool.

Classic Example (Shift 3)

Plaintext: THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG

Ciphertext: WKH TXLFN EURZQ IRA MXPSV RYHU WKH ODCB GRJ

This famous pangram (a sentence containing every letter of the alphabet) demonstrates how each letter transforms while spaces remain unchanged. Notice how the pattern is consistent throughout the entire message, making it vulnerable to analysis.

Encrypting "HELLO"

Let's trace through the encryption of a simple word using Caesar's shift of 3:

- H (position 7) + 3 = K (position 10)

- E (position 4) + 3 = H (position 7)

- L (position 11) + 3 = O (position 14)

- L (position 11) + 3 = O (position 14)

- O (position 14) + 3 = R (position 17)

Result: KHOOR

Decrypting "KHOOR"

To decrypt, we shift backward by 3:

- K (position 10) - 3 = H (position 7)

- H (position 7) - 3 = E (position 4)

- O (position 14) - 3 = L (position 11)

- O (position 14) - 3 = L (position 11)

- R (position 17) - 3 = O (position 14)

Result: HELLO

Different Shift Values

The same message looks completely different with different shift values:

| Shift | HELLO becomes |

|---|---|

| 1 | IFMMP |

| 3 | KHOOR |

| 13 | URYYB |

| 25 | GDKKN |

Shift 13, known as ROT13, has special properties we'll explore later. Each shift value creates a distinct cipher alphabet, though all are equally easy to break.

Breaking the Caesar Cipher: Historical Cryptanalysis

While the Caesar cipher served its purpose for centuries, it was eventually rendered useless by the development of systematic methods to break it. This turning point represents one of the most significant developments in caesar cipher history.

Al-Kindi and the Birth of Cryptanalysis

The first known technique for breaking substitution ciphers was developed by the Arab polymath Al-Kindi in the 9th century AD—roughly 900 years after Caesar's death. In his groundbreaking work "Risalah fi Istikhraj al-Mu'amma" (A Treatise on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages), Al-Kindi introduced the concept of frequency analysis. This innovation fundamentally changed caesar cipher history by making the once-secure cipher trivially breakable.

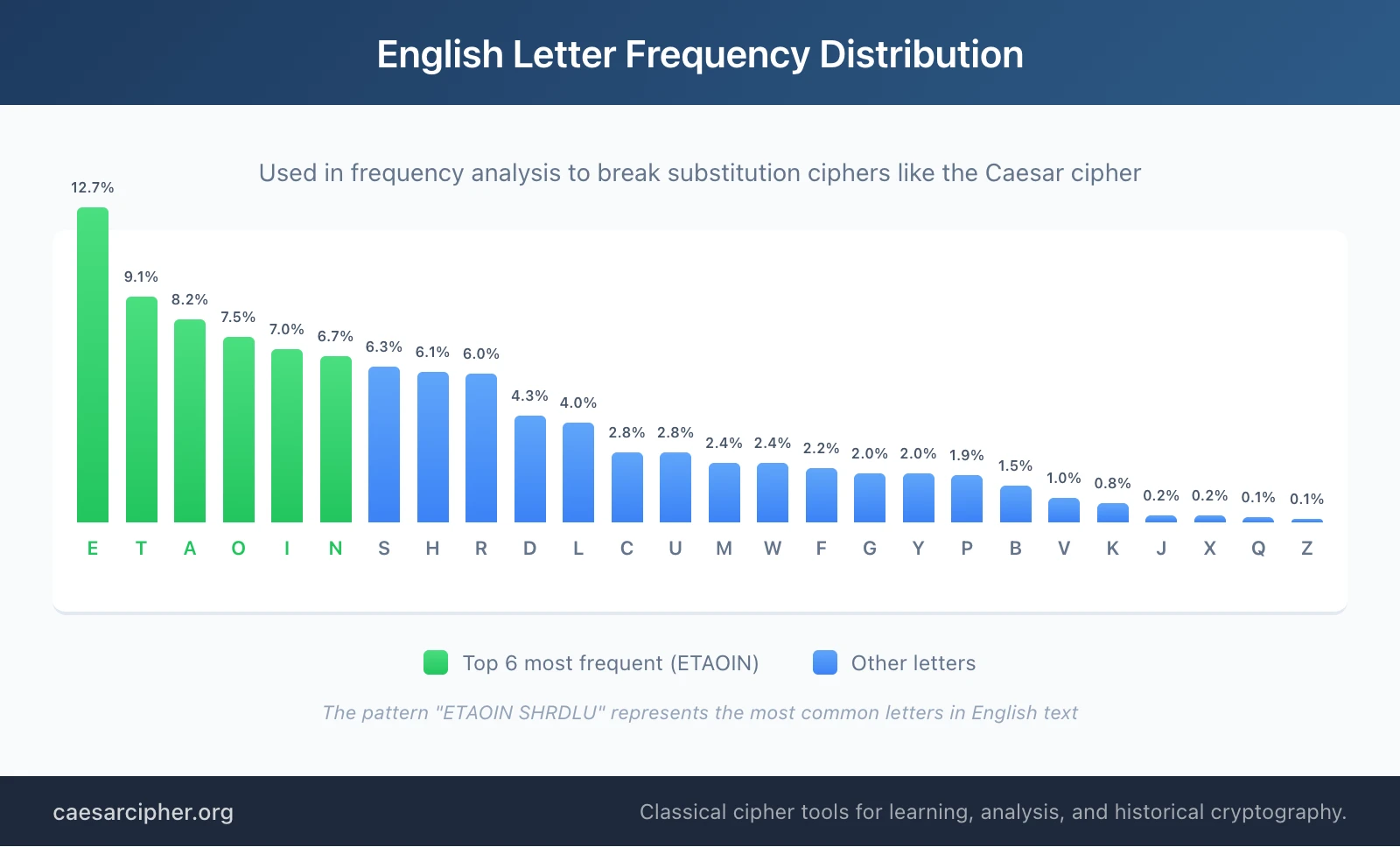

Al-Kindi's insight was simple but revolutionary: in any language, certain letters appear more frequently than others. By analyzing the frequency of letters in an encrypted message and comparing them to known frequencies in the language, a cryptanalyst can deduce the substitution pattern. This technique works against all simple substitution ciphers, including the Caesar cipher.

Frequency Analysis Explained

In English, the most common letters are:

- E (approximately 12% of text)

- T (approximately 9%)

- A (approximately 8%)

- O (approximately 7.5%)

- I (approximately 7%)

If you intercept a Caesar-encrypted English message and find that the letter H appears most frequently, you can hypothesize that H represents E, meaning the cipher uses a shift of 3. This predictable pattern is the Caesar cipher's fundamental weakness.

Brute Force Attack

Even simpler than frequency analysis is the brute force approach. Since the Caesar cipher has only 25 possible keys (shifts of 1 through 25), an attacker can simply try each one until readable text appears. The small keyspace makes exhaustive search trivial.

This process takes mere seconds by hand and milliseconds by computer. It's why the Caesar cipher offers absolutely no security against anyone making a serious attempt to break it. Modern computing has made what was once laboriously slow now instantaneous.

Why It Remained Secure for Caesar

Understanding why the cipher worked for Caesar requires appreciating the historical context. Frequency analysis wouldn't be invented for nearly a millennium. Most of Rome's enemies couldn't read at all. The concept of systematically attacking a cipher didn't exist.

For Caesar's purposes, the cipher needed only to prevent casual reading by captured messengers or curious servants—and it accomplished that goal admirably. This contextual security is an important lesson in caesar cipher history: effective security depends on the threat environment, not absolute strength.

The Caesar Cipher in Military History

The Caesar cipher's association with military communications didn't end with ancient Rome. Its simplicity made it attractive to military forces well into the modern era, sometimes with disastrous results. This extended military use forms a fascinating chapter in caesar cipher history.

Roman Military Communications

Beyond Caesar himself, the Roman military likely continued using substitution ciphers for sensitive communications. The empire's vast territory required constant communication between Rome and distant provinces, and encryption helped protect orders and intelligence reports traveling across potentially hostile regions. Augustus's adoption of the cipher suggests it became standard practice in imperial administration.

The Russian Army Failure (1915)

During World War I, the Russian army provides a cautionary tale about underestimating cryptographic security. According to historian David Kahn in his definitive work "The Codebreakers," the Russians employed the Caesar cipher as a replacement for more complicated systems that proved too difficult for their troops to master. This represents one of the most tragic episodes in caesar cipher history.

The result was catastrophic. German and Austrian cryptanalysts, well-versed in the techniques Al-Kindi had pioneered a thousand years earlier, had no difficulty decrypting Russian messages. The intelligence advantage contributed to significant German victories on the Eastern Front.

This historical episode illustrates a timeless lesson: the tradeoff between usability and security. A cipher that troops cannot correctly implement offers no protection, but a cipher that's too simple offers no security either. The Russians learned this lesson at tremendous cost.

Modern Cases: When the Caesar Cipher Made Headlines

Surprisingly, the ancient Caesar cipher has appeared in 21st-century criminal cases, demonstrating that some people still underestimate its vulnerability. These contemporary incidents add unexpected chapters to caesar cipher history.

Mafia Boss Bernardo Provenzano (2006)

Bernardo Provenzano, the notorious head of the Sicilian Mafia, evaded capture for 43 years while running his criminal empire from hiding. When Italian police finally captured him in 2006, they discovered he had been communicating with his subordinates using a Caesar cipher variant. This case demonstrates how caesar cipher history continues into the modern era.

Provenzano's coded messages, known as "pizzini" (little pieces of paper), used a substitution system where each letter was replaced by a corresponding number. Italian investigators broke the code and used the decoded messages as evidence of his continued leadership of Cosa Nostra.

The case raises an intriguing question: why would a sophisticated criminal organization use such a primitive cipher? The likely answer is that Provenzano, born in 1933 with limited formal education, knew no better method and assumed the cipher would be sufficient to avoid detection. His overconfidence proved to be a critical mistake.

UK Terrorism Case: Rajib Karim (2011)

In a more chilling example, Rajib Karim, a software engineer working for British Airways, was convicted in 2011 of terrorism offenses. Evidence presented at trial showed he had used the Caesar cipher to communicate with Anwar al-Awlaki and other terrorist figures in Bangladesh and Yemen. Ironically, a software engineer should have known better encryption methods existed.

The encrypted messages discussed potential sabotage of aircraft, including exploiting Karim's position as an airline employee. British intelligence services decoded the messages using standard cryptanalytic techniques, and the decrypted communications became key evidence in his conviction. The ease of decryption ensured justice was served.

Why Simple Ciphers Persist

These cases reveal a persistent human tendency to believe that a little secrecy is enough. Without training in cryptography, people assume that any encryption is good encryption. They learn too late that security through obscurity—hiding information by using an unknown method—fails completely once that method becomes known.

The Caesar cipher's weakness isn't a secret. It's taught in introductory cryptography courses precisely because it's so easy to break. Yet the psychological comfort of encoding messages continues to seduce those who don't understand the math. This misplaced confidence is perhaps the most enduring aspect of caesar cipher history.

Legacy and Modern Applications

Despite its cryptographic worthlessness, the Caesar cipher enjoys a vibrant modern existence in education, entertainment, and internet culture. This ongoing relevance ensures that caesar cipher history continues to be written even today.

ROT13: The Modern Caesar Cipher

ROT13 is a special case of the Caesar cipher that uses a shift of exactly 13 positions. Because the English alphabet has 26 letters, shifting by 13 creates a cipher that's its own inverse: applying ROT13 twice returns the original text. This mathematical elegance made it popular in computing.

This property made ROT13 popular on Usenet and early internet forums for obscuring spoilers, puzzle solutions, and potentially offensive jokes. The convention wasn't about security—everyone knew how to decode ROT13—but about preventing accidental reading.

Even today, ROT13 appears in some software applications and online communities as a quick way to hide text that readers might prefer to reveal voluntarily. This represents perhaps the most benign chapter in caesar cipher history.

Secret Decoder Rings and Children's Toys

Since at least the 1930s, when radio programs like "Little Orphan Annie" included them as promotional items, secret decoder rings have delighted children with the magic of hidden messages. These toys typically implement some version of the Caesar cipher. They've introduced countless young people to cryptographic concepts.

The appeal is timeless: children today still enjoy creating and breaking codes, and the Caesar cipher provides an accessible entry point into the world of cryptography. Through toys and games, caesar cipher history touches new generations every year.

Educational Use

In cryptography education, the Caesar cipher serves as the perfect first lesson. It introduces key concepts—plaintext, ciphertext, keys, encryption, decryption—without the mathematical complexity of modern systems. This pedagogical value ensures the continued study of caesar cipher history.

Computer science students often implement Caesar ciphers as programming exercises, learning about modular arithmetic and character manipulation in the process. The simplicity of the algorithm makes it ideal for teaching fundamental programming concepts.

The cipher also appears regularly in CTF (Capture The Flag) competitions, where cybersecurity enthusiasts solve puzzles that often include classic ciphers as warm-up challenges. Understanding historical ciphers helps build intuition for modern cryptanalysis.

Foundation for Modern Cryptography

Historically, the limitations of the Caesar cipher drove the development of more sophisticated methods. The polyalphabetic Vigenère cipher, developed in the 16th century, was a direct response to the weaknesses of monoalphabetic substitution. Progress in cryptography often comes from understanding failures.

The principles of substitution and transposition that the Caesar cipher embodies remain fundamental to cryptographic theory. Modern encryption systems are vastly more complex, but they build on the conceptual foundation that Caesar helped establish. Every cryptographer's journey begins by understanding caesar cipher history and its lessons about both security and vulnerability.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called the Caesar cipher?

The cipher is called the Caesar cipher because Julius Caesar used this encryption method to protect his military communications. The Roman historian Suetonius documented this practice in the 2nd century AD, cementing the association with Rome's most famous general. This naming convention ensures that caesar cipher history always points back to its Roman origins.

What shift did Caesar use?

Julius Caesar used a shift of 3, meaning A became D, B became E, and so on. His nephew Augustus later used a shift of 1 with a different approach for the letter Z. The shift of 3 has become the canonical example when teaching caesar cipher history.

Is the Caesar cipher secure?

No, the Caesar cipher is not secure by modern standards. With only 25 possible keys, it can be broken in seconds using brute force or frequency analysis. It should never be used to protect genuinely sensitive information.

When was the Caesar cipher invented?

The Caesar cipher was used by Julius Caesar around 100-44 BC, making it over 2,000 years old. It's one of the oldest documented encryption techniques in history.

How many possible keys does the Caesar cipher have?

The Caesar cipher has 25 possible keys, representing shifts of 1 through 25 positions. A shift of 0 or 26 would leave the message unchanged and thus provide no encryption.

What is frequency analysis?

Frequency analysis is a cryptanalysis technique that exploits the fact that letters appear at predictable rates in a language. By comparing letter frequencies in ciphertext to expected frequencies, analysts can determine the encryption key. Al-Kindi invented this method in the 9th century.

Did Augustus use the same cipher as Caesar?

No, Augustus used a shift of 1 instead of 3, and he didn't wrap the alphabet around. Instead of shifting Z to A, he wrote "AA" to represent Z, creating a slightly different system from his uncle's.

Is ROT13 a Caesar cipher?

Yes, ROT13 is a specific case of the Caesar cipher using a shift of exactly 13. Its unique property is that it's self-inverse: applying ROT13 twice returns the original message.

Who broke the Caesar cipher first?

The first systematic method for breaking substitution ciphers was developed by Al-Kindi, an Arab polymath, in the 9th century—roughly 900 years after Caesar's death. His frequency analysis technique remains effective today.

Are Caesar ciphers still used today?

While not used for actual security, Caesar ciphers appear in education, children's toys, puzzles, and CTF competitions. Some criminals have attempted to use them, unsuccessfully, as the cases of Provenzano and Karim demonstrate.

Summary: The Enduring Legacy of the Caesar Cipher

Understanding caesar cipher history reveals remarkable insights about the evolution of secret communication. From its origins in the military campaigns of ancient Rome to its modern appearances in courtrooms and classrooms, this simple encryption technique has demonstrated extraordinary longevity. The caesar cipher history spans over two millennia of human innovation and adaptation.

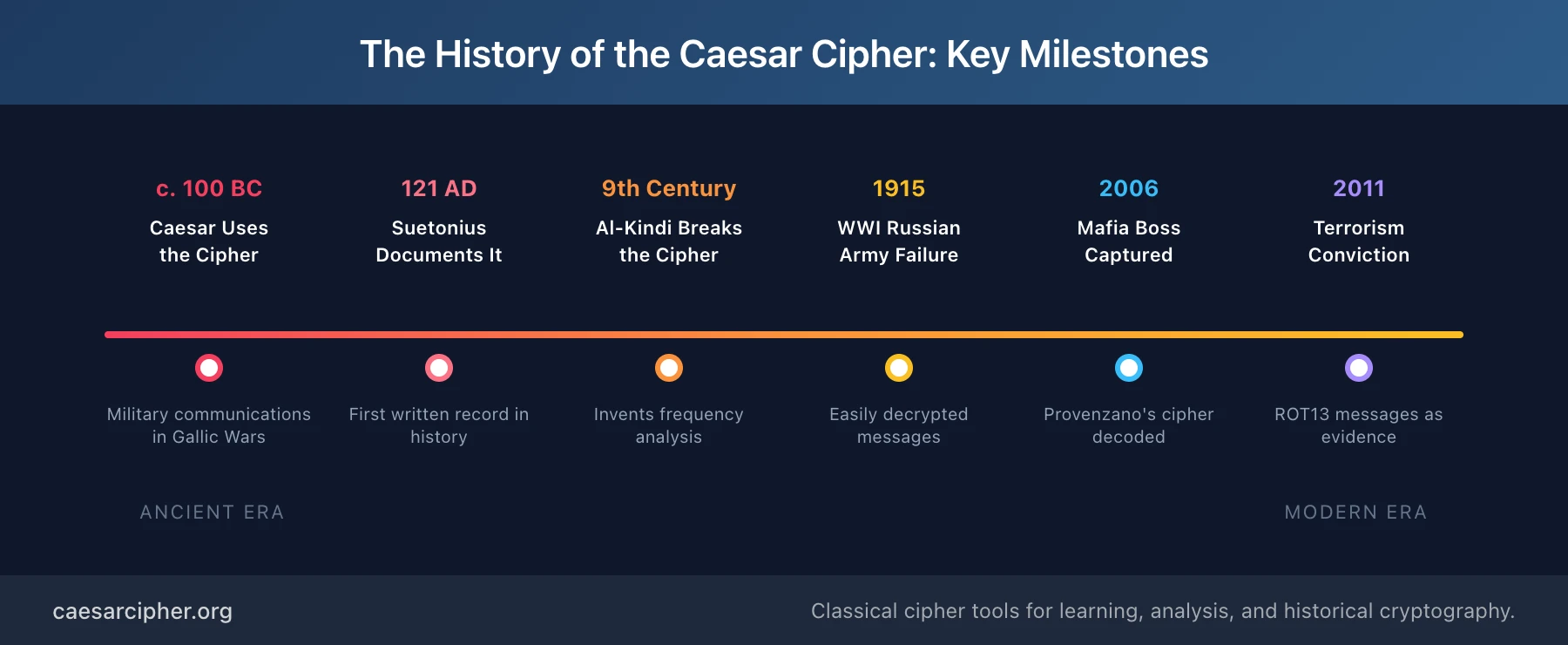

Key milestones in the caesar cipher history include:

- c. 100 BC: Julius Caesar begins using the shift-3 cipher for military communications

- c. 44 BC: Caesar's death ends his personal use, but the technique survives

- 121 AD: Suetonius documents Caesar's cipher for posterity

- 9th century: Al-Kindi develops frequency analysis, rendering the cipher breakable

- 1915: Russian Army's failed use demonstrates military consequences of weak encryption

- 2006: Mafia boss Provenzano captured, Caesar cipher evidence used against him

- 2011: Terrorist Karim convicted using decoded Caesar cipher messages

The Caesar cipher's true legacy lies not in its security—which was always limited—but in its role as a stepping stone. It introduced fundamental concepts that evolved into the sophisticated encryption protecting our digital world. Every secure website, encrypted message, and protected database owes a conceptual debt to the simple idea that Caesar pioneered: systematic transformation using a shared secret.

For anyone interested in cryptography, the Caesar cipher remains the perfect starting point—simple enough to understand completely, yet rich enough to illustrate principles that apply to far more complex systems. Two thousand years after Julius Caesar encoded his first military dispatch, we continue to learn from his ancient cipher. The story of caesar cipher history reminds us that even the simplest ideas can have profound and lasting impact on human civilization.